Review by Woodrow Phoenix

“By necessity we must infiltrate popular mediums. We are building a business-based art movement. This is not new. Admitting it is. … Law: If you want better media, go make it. … Capitalism for good or ill is the river in which we sink or swim, and stocks the supermarket.”

Gary Panter’s ROZZ-TOX Manifesto (1980) inspired a lot of people to try and infuse commercial mass-market products with their personal sensibilities, most notably Matt Groening who succeeded in that goal with The Simpsons and Futurama. Panter himself worked on many corporate projects, illustrating album covers for Frank Zappa and Iggy Pop, for magazines such as Rolling Stone and Time, and a long partnership with Paul Reubens for Pee Wee’s Playhouse where his set design earned him three Emmys. Although he’s renowned as a great designer and illustrator (the Chrysler Award For Design Excellence in 2000 is another one of his awards) it’s not acknowledged what a good writer Gary Panter is, starting with that manifesto.

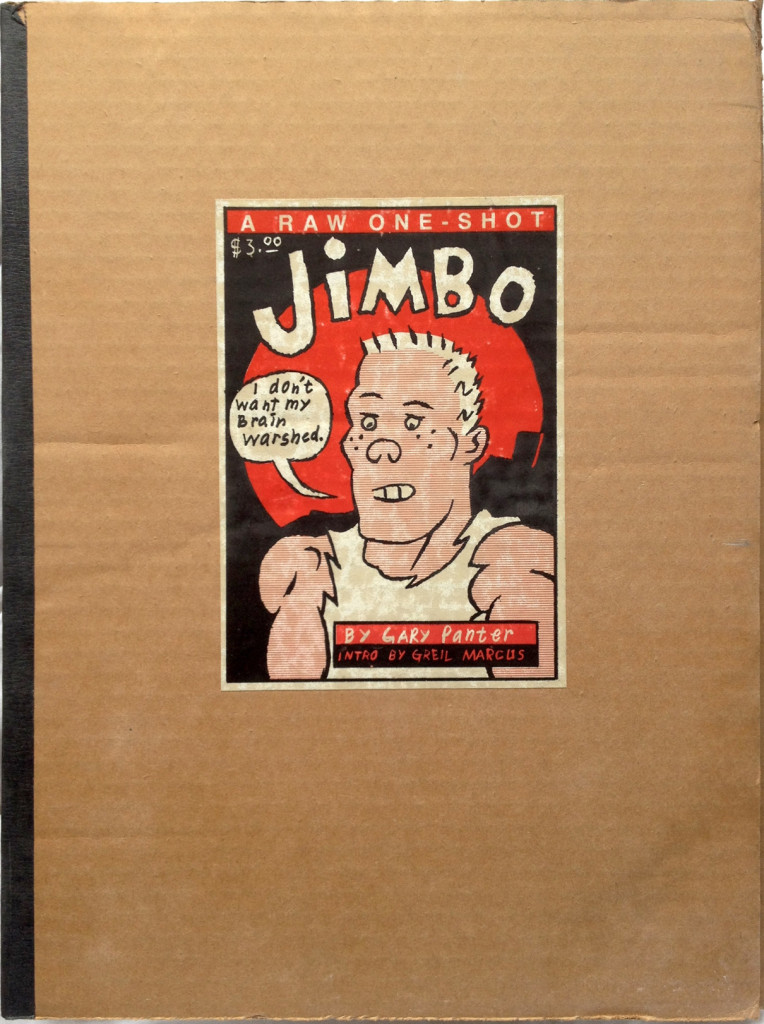

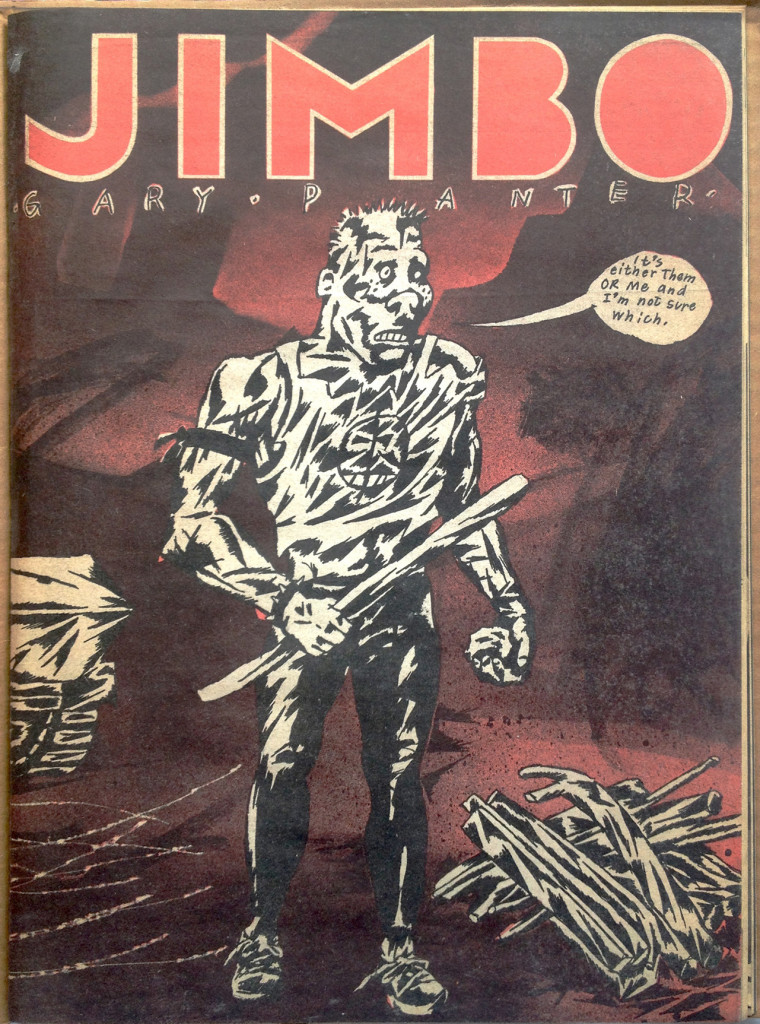

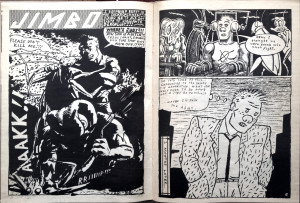

Jimbo is a tabloid newspaper-sized book printed on newsprint and bound in a cardboard cover, the spine taped with black electrical tape and a black and red label glued onto the front. That combination of handmade and industrial aesthetics instantly signals that something interesting is going on, which is exactly what Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, publishers of Raw magazine wanted you to think. Inside is a riot of punk graphics, experimental comics storytelling and amazing drawing that vibrates with an energy you can still feel when you look at the generously-sized, yellowed pages today. Panter wrote and drew the adventures of his punk man-boy Jimbo for the Los Angeles punk zine Slash and the story collected in this ‘Raw one-shot’ book originally appeared between 1978 and 1980.

Jimbo starts off with some funny and relatively mundane slice-of-life stuff with a slapstick edge, drawn with a ferocious crosshatched and messily laid out line, that almost instantly switches to bigger and bolder images, using the large space of a tabloid page to create striking graphic compositions. And then Panter just keeps collapsing boundaries and constantly shifting styles as the story continues. On one level there’s a search for meaning and self-definition driving the continuous visual experimentation, with poetic and sometimes genuinely serious philosophical moments mixed in with the jokes. A lot of the words in these comics are as striking and memorable as the visuals. Then there’s a plot involving Jimbo’s friend Smoggo introducing him to his sister Judy, who spends a blissful night with Jimbo before being kidnapped in a bar by a group of giant cockroaches. These antagonists are led by King Ducko, a giant cockroach who wears a Donald Duck mask. As you’d expect with an exploration of punk aesthetics and what they were a reaction to, Jimbo builds to an apocalyptic ending – which isn’t the end but more of a reflection on stories and endings themselves. It’s a tour-de-force of comics storytelling. And in 1982 it was only $3. What a steal.

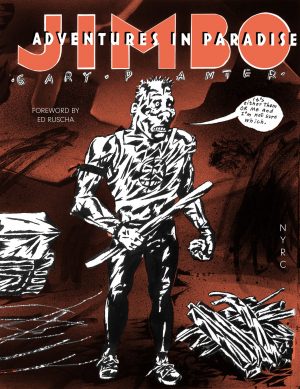

This edition is long out of print. It’s relatively easy to find online, but unsurprisingly very expensive considering what a vital document this book is. You can find it reprinted in its entirety without the cardboard cover and the yellowing newsprint paper, in the second edition of Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise from NYRB. Further Jimbo books by Gary Panter not yet reprinted include Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006).