Review by Graham Johnstone

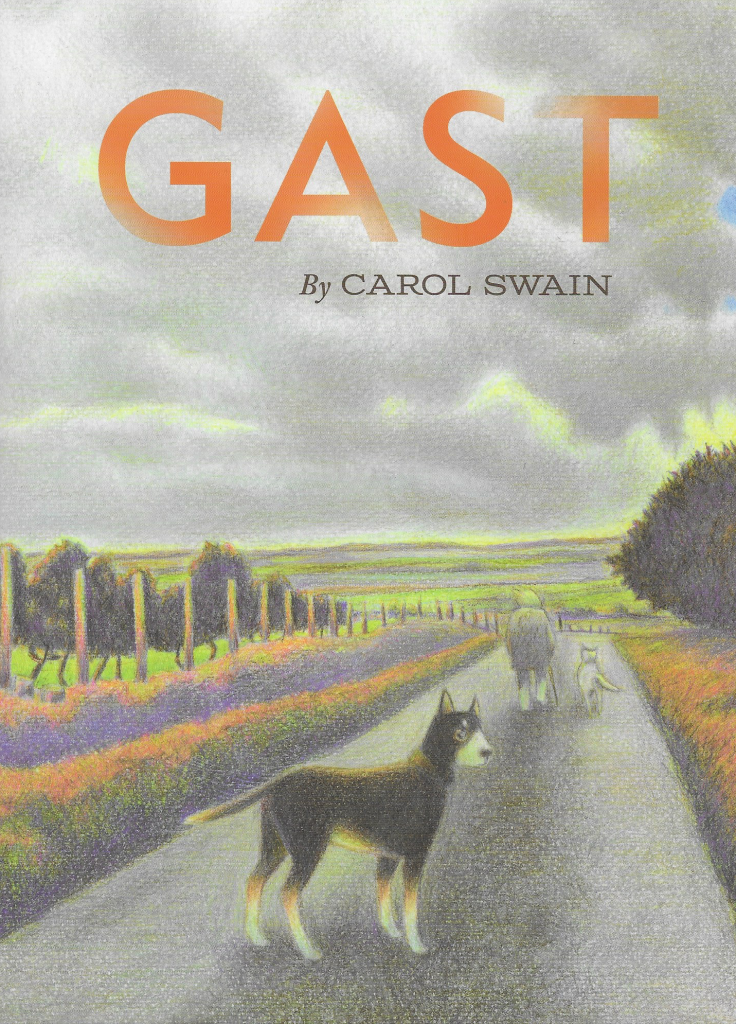

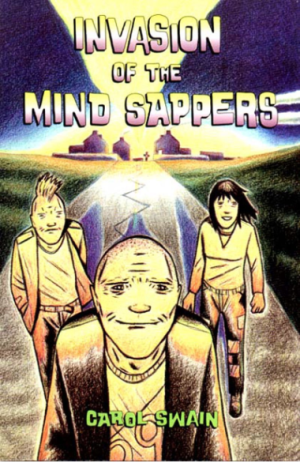

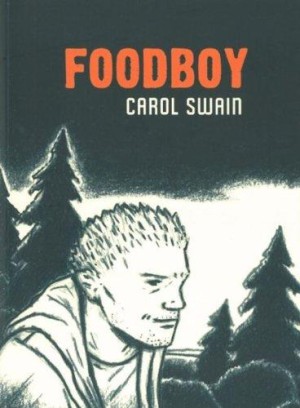

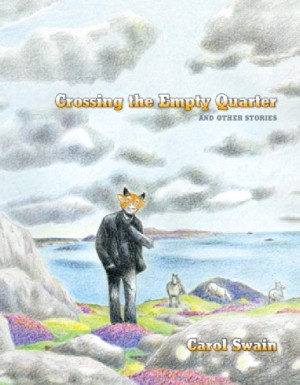

Carol Swain’s 2014 Gast, forms a loose trilogy with her earlier Foodboy (1996) and Invasion of the Mind Sappers (2004). All are set in fictional Welsh village Llanparc, and explore the joys and constraints of rural life. The pre-teen protagonist of Gast is also presumably the same Helen as the teenager in Mind Sappers, but each book is self-contained.

Young Helen’s family have just moved from London when news emerges of the death of local farmer Emrys. As Helen finds out about him, this becomes a mystery she wants to solve. However, it’s no edge of the seat thriller. As those familiar with Swain’s work might expect, it’s a more gentle, reflective story, following Helen’s efforts to find out more about the man and why he died. It’s less a whodunnit than a whydunnit. He had, we’re told again and again, no real friends. This may have been because he was different in this very traditional community, or as they tell it, that his vulnerability turned into defensiveness – keeping everyone at a distance. In the course of Helen’s enquiries she meets, Bill ‘the eggman’, the Avon lady (cosmetics salesperson), and, showing how far she literally has to go – the woman who served him lunch everyday across the border in England. She gradually pieces together a picture of the life and tragic death of someone she never met.

Helen even talks with the animals, hearing their thoughts on the death, and sometimes how it affects them: Emrys’ two sheepdogs; Jup the aging ram, his career as a stud looking like it’s over; even the swallows that flock around her for a time. These are no anthropomorphised funny animals. They’re realistically drawn, in fact more so than the people, which might seem a jarring device in a low-key realistic story, but Helen’s youth and love of animals, make it fit seamlessly.

Part of the subtle beauty of Swain’s story is that there is no villain, or a single malicious person or animal. Neither is there (like say J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls), any obvious chain of complicity in the death. There’s no hostility expressed toward Emrys, or condemnation of the way he lived his life, only a set of reactions to how it ended. ‘Gast’ (pronounced ‘Gaest’) is Welsh for ‘bitch’, but used by the dogs (for both Helen and Emrys), to mean ‘female’ without negative connotation

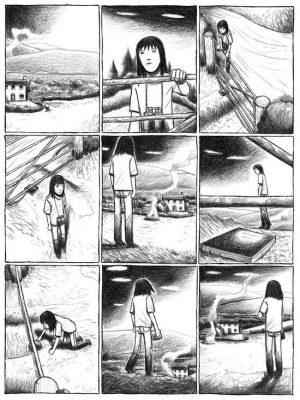

The rural setting is so beautifully and evocatively portrayed, that it’s almost a character in the story, and there are many wordless sequences simply showing Helen walking around – a figure in a landscape. Initially known for short poetic comics, Swain proved from her first long-form work a mastery of novelistic structure: cause and effect plot, turning points, revelations, and escalation. While Gast covers most of those bases, the overall effect is something different. It’s close to what film scholars call poetic documentary – concerned with movement, space, rhythm and ‘material properties’, in this case, of the rural landscape. This effect is reinforced by the lack of voiceover, minimal dialogue, and indeed the filmic black and white rendering.

Swain trained as a painter, which perhaps helped her sidestep comics line art traditions and develop a more subtly tonal pencil/charcoal technique. Innovative at the time, there’s still little to compare to it. She uses the same nine panel grid on every page, but with the dazzling cinematography, combined with elegant panel and page designs you’ll hardly notice.

As always, Swain’s art and story are perfectly matched and integrated – she’s virtually created her own genre, of which this is the best example yet.