Review by Graham Johnstone

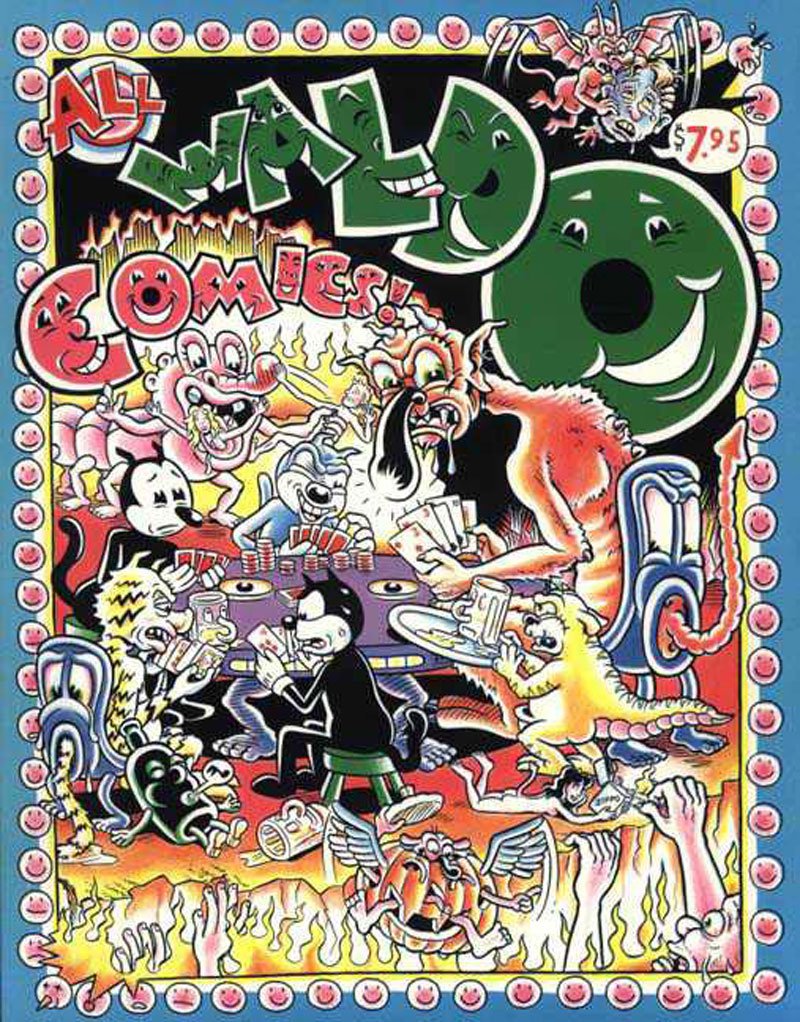

This Waldo isn’t the chap in stripes you have to find in a crowd scene (outside America, actually called Where’s Wally), but an anthropomorphic blue cat with the number 1 on his belly. Despite that you still might not see him in a crowd, as he only appears to, what we might charitably call, the select few. Far from his smiling namesake, Kim Deitch’s Waldo is a hard-living hedonist, with a streak of mischief bordering on malevolence.

Kim Deitch was a key figure the 1960s heyday of American underground ‘comix’. He was an editor for Gothic Blimp Works, (the comics spin-off of counter-cultural newspaper The East Village Other), where he published his first Waldo stories. Far from being a period footnote though, Deitch’s best work was still to come, and at the start of his seventh decade in the field he’s as productive as ever. Deitch always had a unique take on the underground culture: sex and drugs may drive the stories, but they’re never centre stage, as they often are with Crumb and Shelton, respectively. Some of Deitch’s earliest work had obvious shout-outs to psychedelia, particularly literal flower child Sunshine Girl. There’s little of that here, but his breaking free of the constraining grid of panels chimes with psychedelia. It’s a significant declaration of intent, but these early panel layouts often need clarifying arrows, and fall well short of, say, Gene Colan’s (contemporary) experimental layouts on Doctor Strange.

‘Deja Vu’, from 1969, highlights the counter-culture’s distrust of the establishment. A cabal of military, state and science, subject Waldo to an experiment to weaponise cats’ legendary nine lives. This turns Waldo into – yes – nine cats, each with a number on their belly, with the ‘real’ Waldo being number 1. It’s idea packed, heavily plotted and fast-paced, though it lacks the finesse of the later stories. The art is particularly dense, presumably being reduced from Blimp Works’ tabloid format.

‘Blue but True’, from two years later, unfolds at a more leisurely pace. It’s a romantic tragedy turned farcical comedy. Waldo and girlfriend Kitty are kept apart in different wings of a prison. Waldo’s escape is engineered by his criminal bosses, who double cross him in a hail of bullets, just as Father Christmas arrives with a letter meant to change everything. Such absurdly intricate plotting would become characteristic of Deitch, though, again, he’d refine it in later stories.

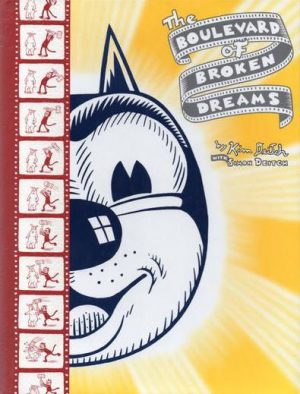

‘The Waldo Lowdown’ from 1975, has the cat ‘befriend’ Jack Mishkin after his release from Berndale Acres Sanitarium. Deitch deftly and amusingly creates ambiguity around whether Waldo is a supernatural being that others can’t see, or simply Mishkin’s delusion. This confidently written and drawn single page, is a further take on Waldo’s origin, a prelude to Mishkin’s story, (Boulevard of Broken Dreams), and introduces Deitch’s long-term obsession with the shady corners of popular culture.

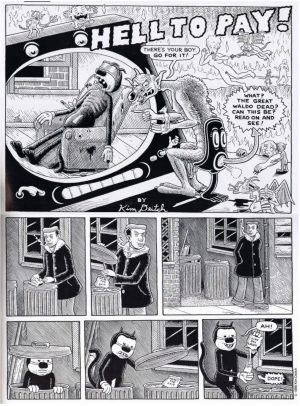

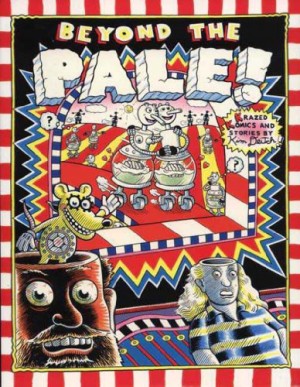

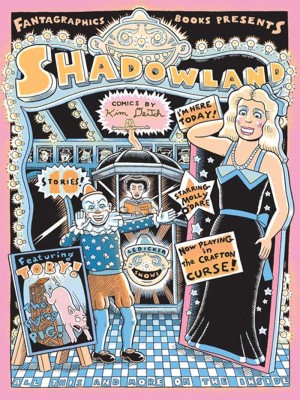

This 1992 volume is effectively a companion volume to 1989’s Beyond the Pale, a similarly chronological collection of Deitch’s non-Waldo shorts to date. Much of the critique of that volume applies: his early pages have a naive charm, and show his formative attempts at toning, page-design, lettering and logos, elements he has absolutely mastered by 1986’s ‘Hell To Pay’ (pictured). Each of the five stories here is a marked improvement over the last.

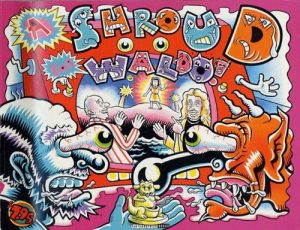

All Waldo Comics is misnamed, as the cat would be a regular, if often uninvited presence in Deitch’s overlapping meta-narrative. Moreover, Waldo doesn’t appear in the final, and most satisfying story ‘Mrs Holla and the Magic Ring’. However it introduces Buster Braun and his daughter Evie, and serves as a prelude to Deitch’s next project A Shroud for Waldo.