Review by Frank Plowright

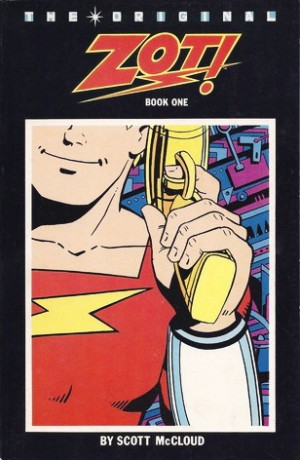

The long out of print Kitchen Sink book gathered Zot’s initial appearances in ten colour chapters originally published between 1984 and 1985. When that didn’t pay off financially, a decision was taken to remove the colour and take a hiatus.

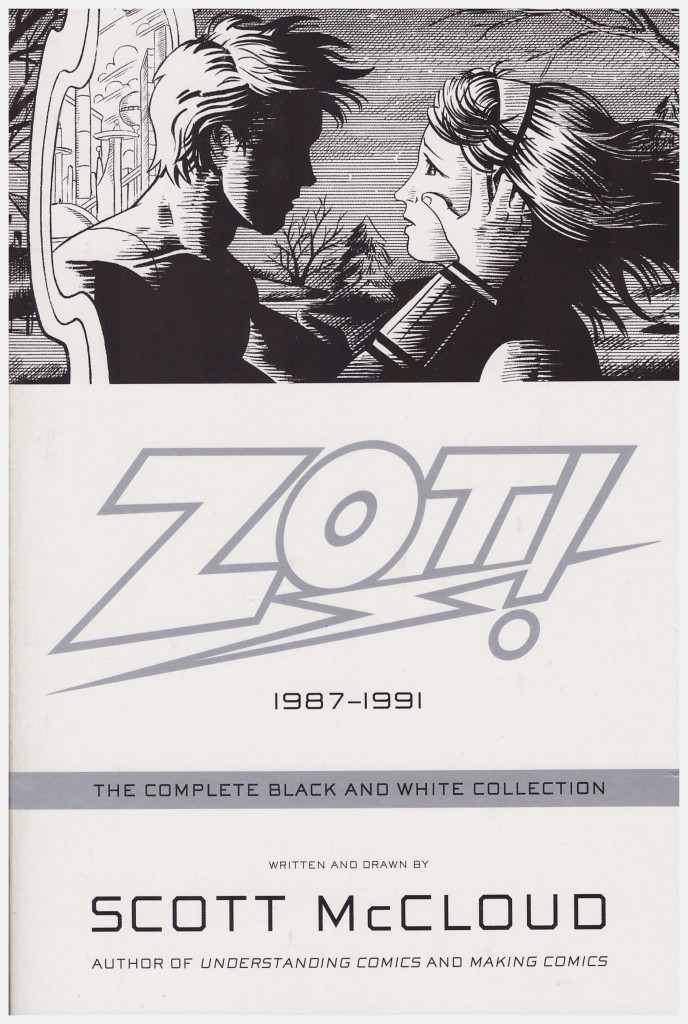

McCloud returned to Zot eighteen months later, and it’s that period until the final issues in 1991 that are reprinted here in a package clocking in at a bulky 575 pages at a size midway between A5 and the traditional US comic format. It’s copiously annotated by McCloud who also made a few artistic improvements for the sake of consistency. Completists should note that what were originally Zot issues 19 and 20 are only present in the form of thumbnails provided by McCloud to Chuck Austen who drew those comics.

The opening seventeen chapters are much the same in tone as those that preceded them, although McCloud is more confident and experimental. There are more apes, Dekko and 9 Jack 9 return, and the fun, awe and joyous characterisation survive the lack of colour. McCloud has become a far better artist, displayed in his composition and characters, and he extends the wonder by ensuring Jenny Weaver’s friends also visit Zot’s world, where it’s perpetually 1965. This material was all previously spread over two collections published by Kitchen Sink in the 1990s.

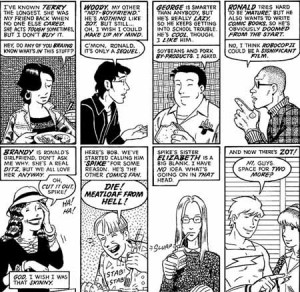

Then something very interesting occurs. Having founded his series on the Manga rush of an optimistic superhero, McCloud found himself far more intrigued by the interaction between his teenage characters, and the story opportunities they provided. He shifted focus, set the stories entirely on Earth, and began to explore the group dynamics between Jenny and her friends.

Love and Rockets had already moved into the territory, but this was an otherwise fallow field for American comics at least, still stuck in the Archie cycle as far as strips about non-super teenagers were concerned. Each of the final nine chapters has a different narrative focus, starting with Jenny, and while there is the occasional lapse into cliché and the odd moment rendered commonplace by later recycling elsewhere, these remain exceptionally good stories. McCloud overseeing everything ensures that what was an exceptional device using the comic format remains in place for Terry’s story, perhaps the best here.

A tale in which Jenny and Zot discuss whether they ought to have sex was nominated for an Eisner Award, and remains touching and poignant, despite McCloud’s concerns about delivering the humanity with what he considers limited artistic skills. So many gifted artists worry too much about the flaws they think others will see, and it seems he’s no exception.

There’s a rather pleasing ending, and that was it for Zot for twenty years as McCloud’s interest switched again, this time to formalising the mechanics of comics with Understanding Comics. An early and passionate proselytiser of the opportunities of web comics, though, he returned to Zot in 2012 archived on scottmccloud.com.