Review by Frank Plowright

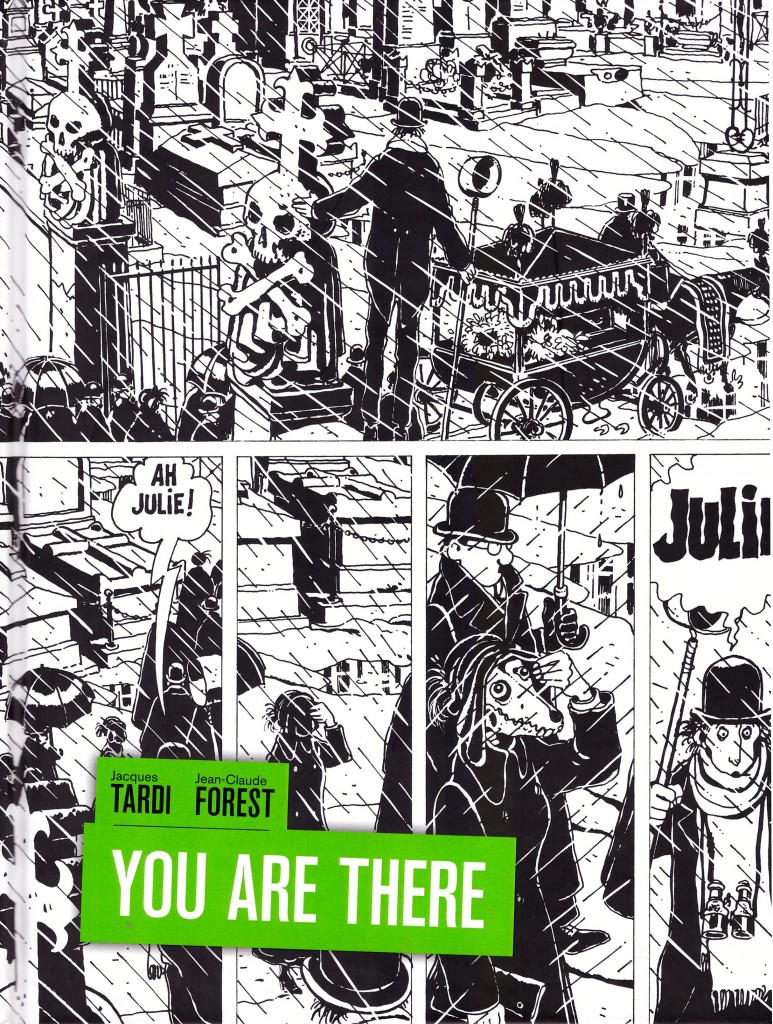

Jean-Claude Forest will forever be most associated with Barbarella’s alluring combination of space adventure with sexual content, but it pales into insignificance when compared with the dense surrealistic fantasy of You Are There. It’s utterly unique, and the bears the hallmark of such work by it being inconceivable that any other writer could have created it.

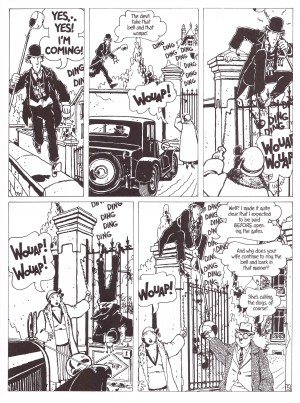

Arthur There is a direct descendent of those who built the once massive Mornemont estate. Family quarrels with distant relatives led to lawsuits, and the resulting victories for those relatives in turn led to the estate being parcelled off into numerous smaller land packages separated by large walls. It’s only the walls themselves and the connecting gates they support that now belong to Arthur, and he patrols them answering calls from those wishing to access their homes, the gates opened on demand in exchange for a small sum. His home is a narrow brick construction precariously perched on a wall, and he dreams that new legal action will revert control of the estate to him.

In a Comics Journal interview Jacques Tardi relates the punishing schedule under which he created You Are There, and dismisses it as a lesser work during an unhappy time, claiming some pages are just hacked out. Some pages do lack Tardi’s customary tightness and detail, but he’s being very hard on himself. The strong composition remains, as does the eye for detail in pages he might consider hacked out, which differ from his normal work only by being slightly sketchier. Tardi bolsters the otherworldliness of the premise by giving the pencil thin Arthur an archaic look that matches his complex speech patterns, and creates a memorable back-up cast.

Once Arthur and the boundaries of his world are thoroughly introduced, other elements come in to play, including a beleaguered President who needs a place of exile, and Julie, a knowing and bawdy young woman whose family occupy a parcel of land. They both feed into the ongoing plot, but the wonder of You Are There has little to do with whether or not Arthur succeeds in restoring the family lands to his control, but the fantastical world he inhabits and the conversations he has.

Forest later denied You Are There is intended as an absurdist satire of how people desperately cling to possessions, power and property, no matter the inconvenience. It very much comes across as such, as this primary characteristic is shared by several cast members. These resemble players of a repertory theatre company slotting into allocated roles according to what Forest had on his mind as he began working on each chapter. The connecting threads only really come into play around the halfway point, by which time Arthur’s world has expanded.

There’s so much to enjoy in You Are There, which is revered in France, yet considerably under-rated in English. Forest delivers a torrent of ideas, and the magnificence of his set up alone would spawn myriad stories for other writers, yet to Forest it’s merely a background. Time after time he astonishes with his twisting of familiarity, and the language throughout is spellbinding, beautifully translated by Kim Thompson to convey the long-winded political justifications and Arthur’s fragile sanity. Tardi picks up on the madness to contribute an eccentricity that never approaches farce until the deliberately over the top conclusion, and both creators supply fine details that may be missed in the rush of a first reading. As far as surreal fantasy graphic novels are concerned, You Are There is top of the range.