Review by Frank Plowright

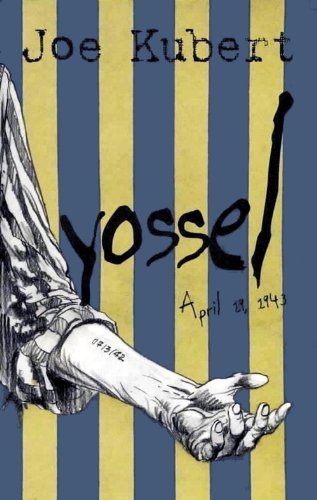

April 19th 1943 is one of many days of infamy during World War II. Having occupied Poland since 1939, the Nazis began confining the Jewish populations to tightly packed ghettos, with the Polish capital of Warsaw having the largest. The lowest estimates reckon at its peak 300,000 people were crammed into an area of just three square kilometres. In 1942 forced deportations to the death camps began, and after one unsuccessful uprising in January 1943 another began on April 19th. The consequences were appalling, with 13,000 deaths, and Yossel is Joe Kubert’s account of what happened.

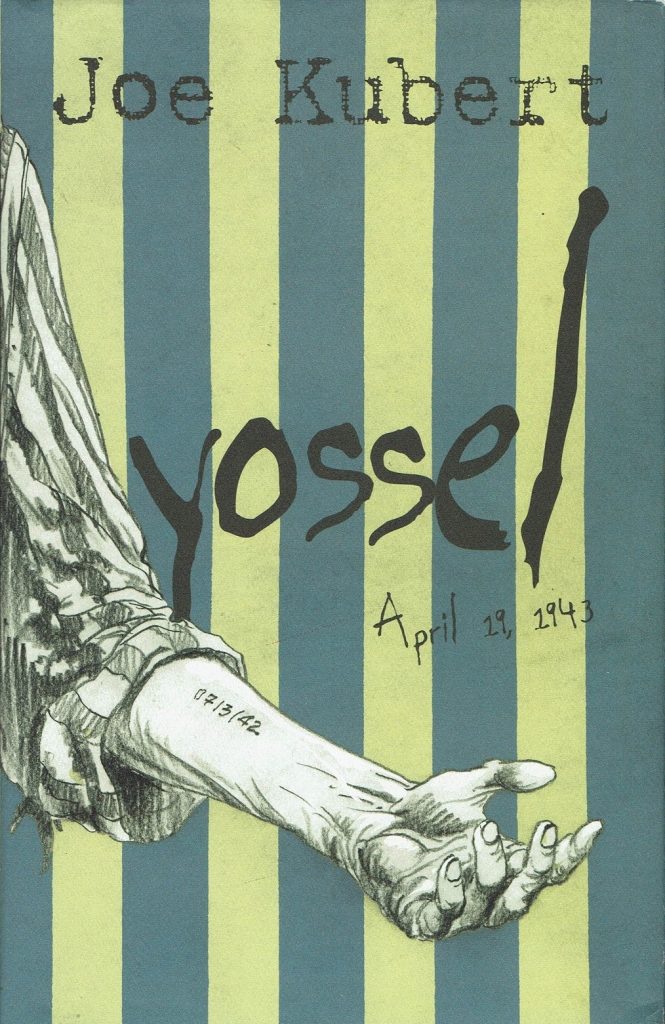

Yossel showcases a very different approach from Kubert’s usual comics work. Drawing in pencil alone conveys an urgency, and he adds to that by not bothering with panel borders, his years of expertise ensuring the story is easily followed despite the illustrations not being contained. Detailed portraits are combined with hastily sketched, impressionistic illustrations of devastation. He draws his version of events not just from historical records, but also from letters sent to his own family by friends and relatives who survived.

Kubert imagines how life could have been for him had his family remained in Poland rather than emigrating to the USA in 1926, Yossel being his stand-in, the talented artist compelled to draw from a young age. Via text boxes and illustrations he runs through his alternative family’s life from just before the knock at the door telling them they were to be moved into the ghetto. Up to fifteen people shared a single room without water or heat, told they would be shot on sight outside after dark.

By personalising the story Kubert gives it greater emotional weight than a bare accounting of facts would do, increased by the illustrations being confined to what Yossel witnesses and hears. The account of the Warsaw uprising actually occupies less than half the book, those events bookending the harrowing testimony of a death camp escapee who returns to the ghetto with first hand experience of what had only previously been suspected.

The few references to Kubert’s 1940s career are intrusive. A scene near the end in a time of crisis has the ideas pouring from Yossel as he conceives how assorted characters could deal with the Nazis then closing in on the ghetto survivors. It has a narrative purpose of the desperate wish for anything that might prevent a seemingly inevitable fate, but is too far removed from the reality applied to the remainder of this bleak, but very moving story.

Kubert’s intention was to leave a lasting statement about what happened to people his parents knew, but sadly iBooks was a short-lived publisher and his Warsaw account briefly sunk with them. Used copies now command very high prices, but thankfully DC supplied a reissue in 2011.