Review by Ian Keogh

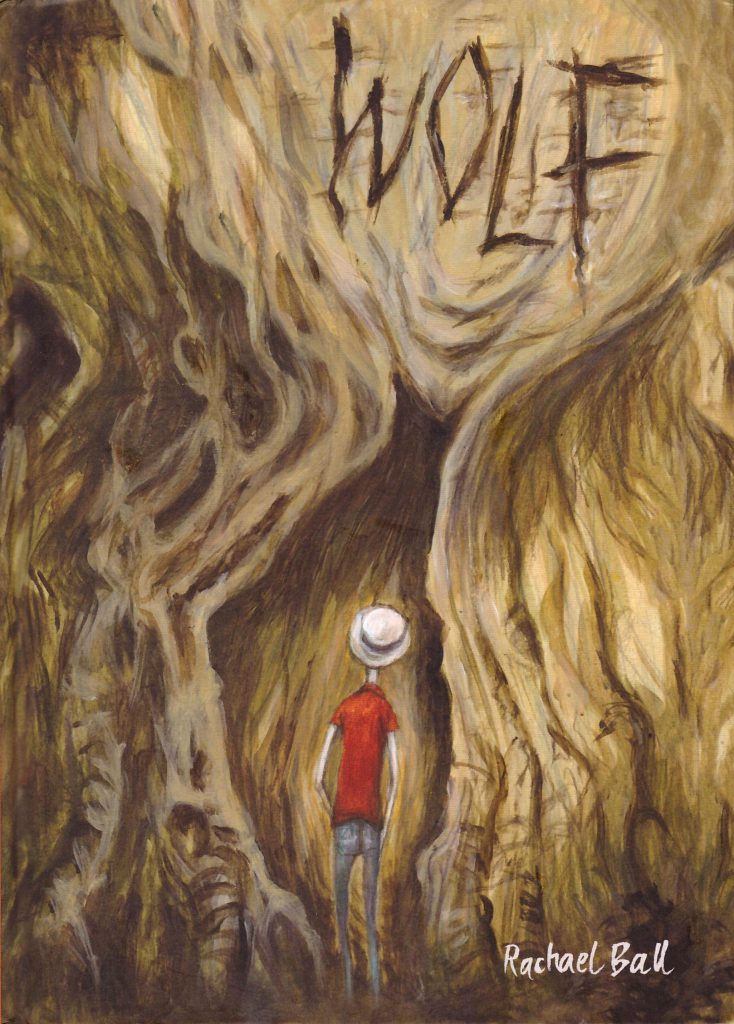

Hugo has a close relationship with his knowledgable father, who’s instilled a love of nature in him. Rachael Ball spends the opening chapter of Wolf charmingly defining this relationship, her loose pencilled pages rife with the joy of exploration and discovery. As the youngest of three children it’s Hugo who’s most affected when it’s necessary to move from a large house in the country to terraced town accommodation, and his response is to keep himself largely to a tent inside the house and eat only eggs. Other circumstances are relevant, but as long as you don’t read the back cover blurb first, Ball springs a real surprise, so let’s keep it that way.

She has a fine memory for a 1970s childhood, the expressions, and the forgotten ephemera playing a part, but most important is Hugo seeing the 1960s Time Machine film on TV and deciding he’s going to make his own time machine. The secret known, it’s a heartbreakingly impossible solution to a problem that’s not going to be solved. On board to help is Icarus, the strange kid from next door, but a necessary part is only obtainable from another neighbour’s garden, already identified as reclusive and supposedly terrifying, known to the local kids as the Wolfman.

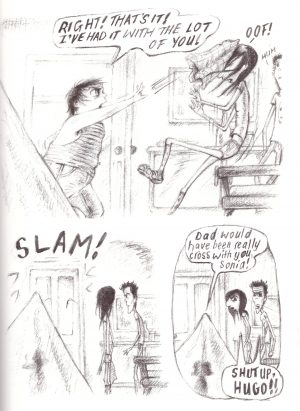

Some revelations are going to be predictable, and in one sense Ball is travelling a well worn path of sentimentality with Wolf, but within that she surprises. Hugo’s personality is constructed with precision, this with sentimentality absent, Ball acknowledging that despite us always remembering the good times, young children can equally be little gits. Hugo’s viewpoint is predominant, but attention is also drawn to what passes him by, what he’s incapable of understanding, and it adds a rich poignancy to his wider world.

Ball’s storytelling is leisurely, with plenty of room for silent reflection, yet the large illustrations, never more than four per page and frequently less, and many mood setting shots make Wolf a relatively rapid read despite clocking in at just under three hundred pages. The rapidity is increased by the lack of panel borders, but the compensation is the chance to return and look closely at the art. The characters are beautifully designed, and convey their personalities extremely well, sometimes almost through a fish-eye lens, at other times deliberately distanced. There is a puzzling use of symbolism. The obvious implication of the cover illustration doesn’t have any great relevance, and a symbolic representation of grief is half-hearted, given prominence on a couple of occasions, yet never seen otherwise. As it’s confined to a couple of scenes it doesn’t intrude, but it’s an eccentricity better ignored.

Grief, family life and hope against the odds are eternal themes that combine evocatively in Wolf for a warmly dramatic read about a child’s coping mechanisms. It’s accessible and humane.