Review by Frank Plowright

The summer of 1952 was a good time to be a kid who bought Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, with Carl Barks producing another five top notch ten pagers. Such is the quality that criticising the work is largely a matter of nitpicking.

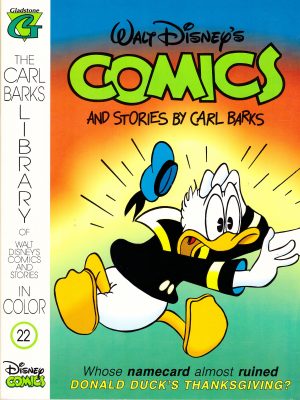

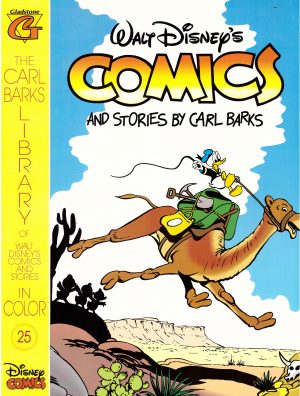

The weakest of them has Donald Duck attempting to pre-empt all possible problems and dangers when Huey, Dewey and Louie are away from school for the summer holidays. His solution is a boat parked on a sandbank several miles from the shore of Lake Erie, the use of an identifiable American location uncommon in Barks’ stories. The gags are relatively tame, and come across as contrived, and the ending appears bolted on. Coincidentally, it’s also the only story in which Donald’s on his best behaviour.

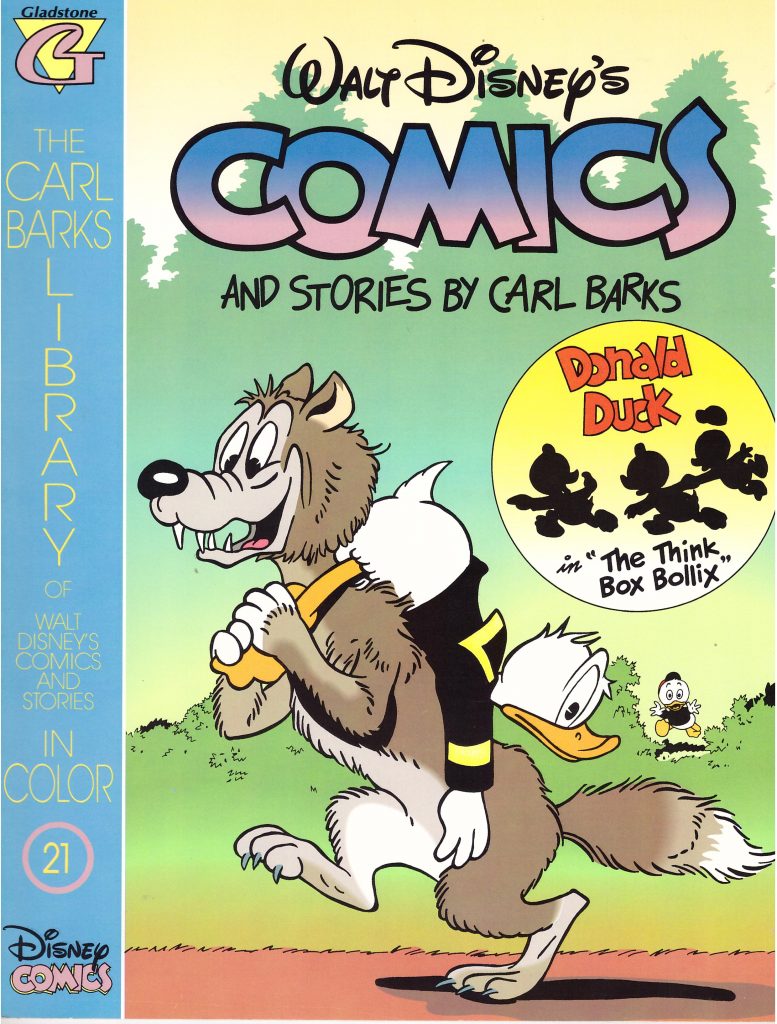

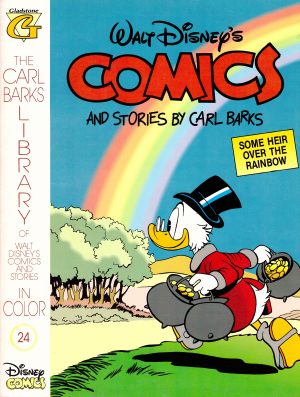

Elsewhere he’s attempting to trick Gladstone Gander, he of the supernatural luck, spend Uncle Scrooge’s money or scare his nephews. As per Barks’ strict moral code, no reward comes from Donald being up to no good. The best story is the opener in which Donald and his nephews follow Gladstone to discover the source of his luck. They obtain his shopping list, which is a collection of incompatible and seemingly impossible items to scrounge for free, yet the polished manner in which Barks has Gladstone acquire these items is beautifully plotted. That, however, is only the opening sequence, as Gladstone’s luck is really put to the test with a seemingly impossible task.

A second seemingly impossible task occurs in the final story where Scrooge is persuaded that the only solution to his money storage problem is to spend and to spend a lot. Against his natural instincts he takes Donald’s advice, although not to the point of accepting a demand of a fifty cent hourly wage. That’s rapidly knocked back to the more customary thirty cents. The pay-off appears to have been devised after receiving a letter in response to a story in the previous collection, in which a reader complained about the bad example set by the excessive spending of Scrooge and Flintheart Glomgold.

Gyro Gearloose also appears twice, once as a gag payoff, and once playing a more central role, having invented a device that will enable animals to think and talk. Rather wonderfully, he just plonks it in the forest to test it, with no thought as to the possible consequences. By 1952 Barks had become comfortable with using the full range of Duckburg’s inhabitants in his short stories, and that would be the norm from now on.