Review by Ian Keogh

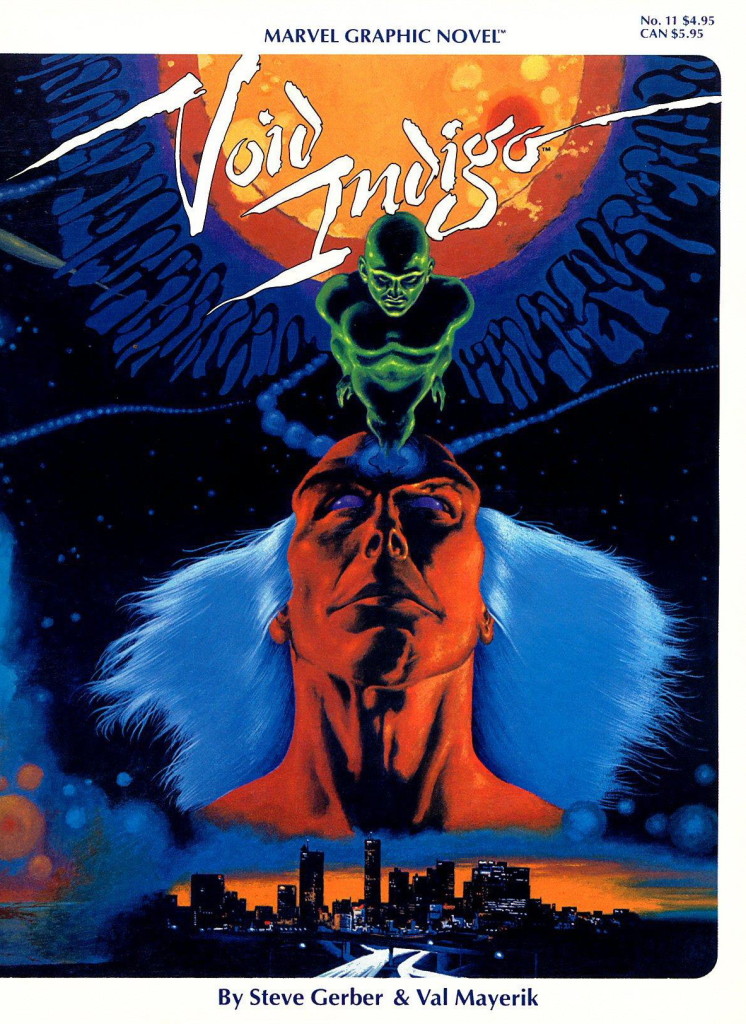

Steve Gerber was always one of Marvel’s most imaginative writers, and given the chance to supply a creator-owned series he certainly didn’t lack ambition. Void Indigo begins with an extended prologue in pre-history, in the age of barbarians, depicted in a spectacular painted spread by Val Mayerik, before moving to the 20th century.

At the dawn of time four old sorcerers meet to seek renewal, to reverse the ravages of age, but being merciless and selfish beings their means of doing so is horrific. Half the book deals with their machinations, necessary background information for the sequences set in the present day. The Void Indigo of the title is the spiritual plane toward which all dead souls gravitate for reincarnation, and the dabblings of the sorcerers have upset a delicate balance that must be rectified. An agent emerges to ensure this occurs, and one of the pertinent players has been reincarnated as an alien spacecraft captain, capriciously named Jhagur.

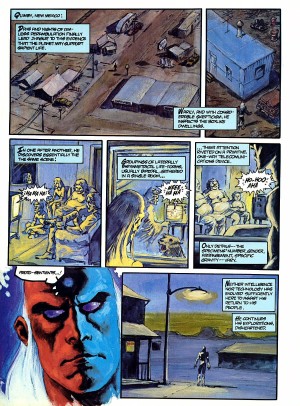

The narrative switch to the present day is still unusual decades on, and characterises the experimental nature of Void Indigo, which at times has the feeling of early Heavy Metal rather than Marvel. Jhagur crash lands on Earth, having been made aware of a mission outstanding for millennia, and quickly hooks up with a young woman who’s attracted to his oddness. Gerber used this device several times in his features, and it’s less effective here as Linette is barely explored as a character.

Much the same could be said of Jhagur. We see him assimilating to Earth culture of the 1980s, but a multitude of descriptive captions do little more than set a story up, which isn’t very satisfactory for what at the time was a prestige production. It’s a shame as there are enough springboards to send Void Indigo spinning off in any number of directions. Instead it resulted in two further standard comics before cancellation. Only Gerber’s very earliest work can be classified as entirely lacking in interest, but Void Indigo’s lack of focus skates it close to that level.

Time hasn’t been kind to Val Mayerik’s art either. He’s a limited storyteller, and the spectacular spreads of the opening sequences soon give way to sketchier and sketchier montages, and a decision to paint the book is soon revealed as misguided. This is compounded by Mayerik’s very primitive use of colour.

When originally published Void Indigo shocked with its graphic depiction of violence, and while this still merits an adult rating, time has passed and it’s no longer as shocking, primarily as it’s no longer the isolated example.