Review by Frank Plowright

Starting this concluding Unknown Soldier volume in World War II Russia appears strange until the relevance is explained. The Kalashnikov rifle was inspired by the desperate wartime siege of Starlingrad where conventional rifles were all-but useless at close quarters, and ever since has been the weapon of choice for invaders and defenders alike. Joshua Dysart’s clever piece is the history of a single gun as it transfers from owner to owner across East Africa. Should we believe the ending? It takes another four chapters to find out.

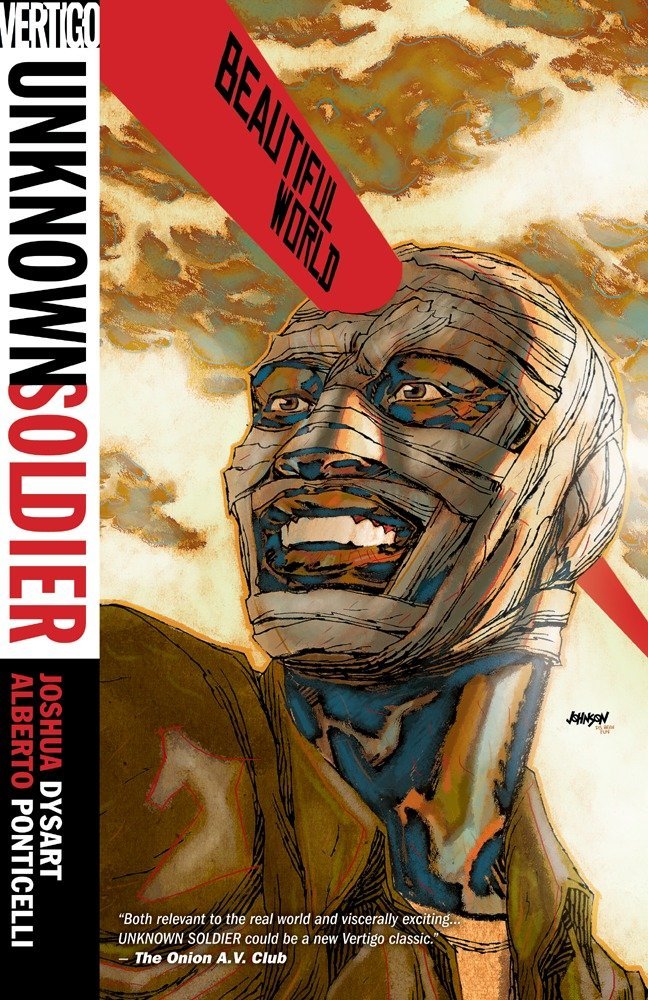

Beautiful World wasn’t always intended to complete Joshua Dysart’s version of Unknown Soldier, yet such is his skill in moving events so naturally to a conclusion, you wouldn’t know if it wasn’t highlighted. As it stands, Moses Lwanga’s story rolls out as a beginning, middle and end over four graphic novels. So, why is it that a doctor providing humanitarian aid to Ugandans during their war in 2002 so readily adapted to combat techniques, becoming almost a force of nature? It’s a clever transformation that played out naturally enough for no-one to question over the course of Easy Kill, but there’s more to it. Much more. In keeping with the tone established this far, there is no great info-dump, but the truth is sifted among the details of a final mission. By the nature of the revelations alone Beautiful World is a different kind of story, humane and in places spiritual, but it’s also an exercise in connection, attaching Moses to previous versions of Unknown Soldier.

After the watercolour exercises in the previous Dry Season, Alberto Ponticelli reverts to the gritty pencil and ink of the earlier graphic novels, more suited to the events and revelations of Beautiful World. While his art can in no way be called decorative, it’s something better: effective. Unknown Soldier requires carnage and atrocity, and Ponticelli’s scratchy lines supply this almost dispassionately, delivering Moses as iconicly striding through the devastation he’s created. The Kalashnikov chapter is drawn by Rick Veitch, at home skipping around the world for the one and two page segments from which the story is constructed.

Central to Unknown Soldier, but rarely seen, is the wretched Joseph Kony, real world abuser of children and responsible for tens of thousands of deaths across Uganda over a twenty year period. Dysart provides a brief essay on his crimes after the story. Disappointingly there is no natural justice, international interest in arresting him having diminished as his influence did, in a country that can provide no oil to the Western world. As of 2019 he remains at large.

The actual final chapter doesn’t quite work, the truth being apparent sooner than intended. While any overly joyful conclusion would betray what Dysart previously presented, what we get isn’t very imaginative. Still, that’s only a dozen pages of an otherwise very readable graphic novel. The final comic page is very clever, set in Sudan several years later, with a real ethical ambivalence about it. Is it a good thing or a bad thing? Every reader will drop to one side or the other.

It’s a rare writer who’ll conceive a better and more memorable take on any war-related character than Garth Ennis, but if you’re limited to just the one version of Unknown Soldier, it ought to be Dysart’s.