Review by Frank Plowright

Adam and Sarah are in their thirties, comfortable enough not to be married despite their long commitment, and seemingly an ideally suited couple. Adam, however, sabotages the relationship as part of his nagging dissatisfaction with life. He puffs up his CV, but the truth is that the few music videos he directed didn’t prove a stepping stone to film, and the hollow feeling within him leads him to other poor choices.

John Harris Dunning’s script is unusually introspective in presenting a deliberately unlikeable and shallow lead who’s metaphorically dragged to the floor and given a good kicking, but what for a long time appears to be Adam entering his mid-life crisis early is actually a dead end. Until that revelation Dunning pulls us along as voyeurs to Adam’s disintegrating life, fuelled by an obsession with a woman he met at a party, and sees in others. Dunning keeps introducing distractions, such as dissections of films, the medium Adam applies to the world, and accompanying this is a neat use of metaphors. Adam’s aware he holds himself back, and his reference for this is a teenage game of dungeons and dragons when he saved the master spell for the final confrontation, only for it not to be needed as someone else stepped in to save the day. Adam’s also contrasted with his even more self-obsessed mate and sounding board Marek, the more imaginative of the pair.

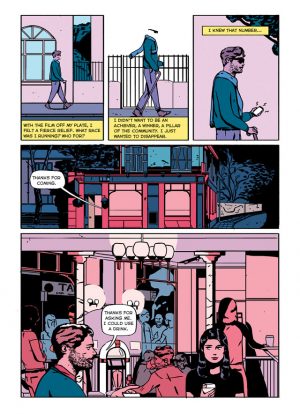

A question that needs to be raised is whether or not a graphic novel is the ideal format for the story Dunning is telling. The theme of lost personalities seems influenced by the work of Daniel Clowes, and that leaves Michael Kennedy drawing banal everyday scenes accompanied by blocks of descriptive text, lapsing into passing film stills and the occasional abstraction. He does this with a distanced passivity, yet there is connection as his eye-catching cover distils Tumult remarkably well into a single illustration. It’s the disturbing aspects of the art that resonate, the times when the plot switches into something almost surreal, such as the manner various personalities see themselves. His bold use of colour is also eye-catching, but occasionally too random.

When Tumult turns, it’s into a cinematic plot of multiple identities, possible brainwashing experimentation and mysterious deaths. Alfred Hitchcock is the model here, and Adam takes the role of Cary Grant-like innocent thrown into fantastic circumstances that swerve beyond him, a modicum of caring emerging from the wreck he’s become. Having been driven into that role, he drops into the background, secondary to the woman from the party and her increasingly complex issues.

There’s no lack of ambition on Dunning’s part, but too much is derivative for anyone with experience of fiction beyond comics, and self-awareness is a constant knowing accompaniment to what feels like two plots fused, leaving Tumult structurally awkward. Adam increasingly means less, his troubles almost incidental once he’s been deconstructed, yet not worth putting back together again. Instead sinister circumstances play out around him. If redemption was to be the issue, a cause worth fighting, then Adam required the level of detailed consideration he receives to begin Tumult. The over-riding noir strangeness means we’re never far from something interesting, but it’s not a cohesive experience that captivates in sustained manner either as character study or crime story.