Review by Woodrow Phoenix

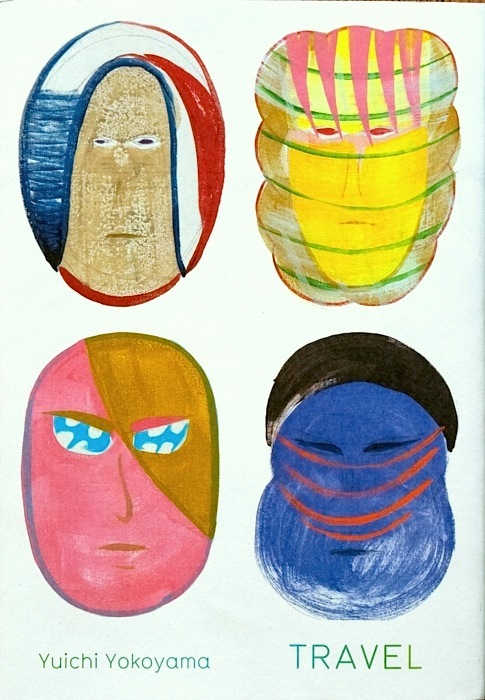

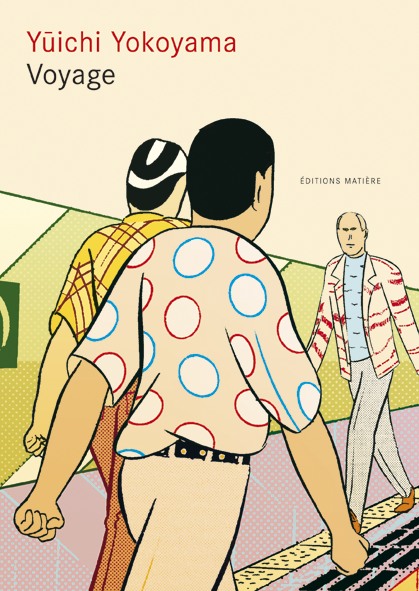

Yuichi Yokoyama’s first book, New Engineering, took the basic components of the comics form, dropped the character-based storytelling and used what remained to dissect time and study how objects move through space. The drawings still had the appearance of typically fantastical science fiction adventure, but what was happening within his forensically detached panels had nothing to do with any conventional ideas about drama. Presented like a graphic novel, it was really an art installation on paper, a non-narrative exhibition of images examining the nature of the physical world.

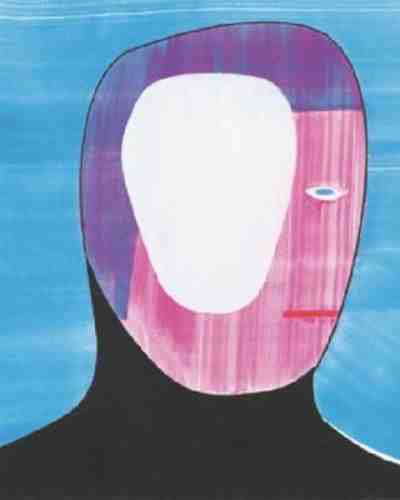

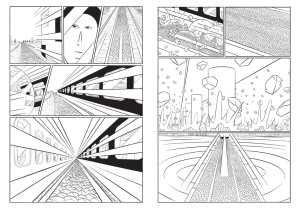

Yokoyama’s second, much longer work, Travel, continues this kind of imagistic exploration. There is one significant difference in the presentation of this next book that changes how the work is read. These comics are wordless, and there are also no sound effects. Three men buy tickets and then board a crowded train, which takes the passengers on a journey through landscapes of strange and complicated vistas, some artificially constructed and others natural and elemental. The speed and forward motion of the first book is now explicitly channelled through a machine combining movement and observation – things seen through windows, continuously changing panoramas to journey through and spectacular perspectives to make sense of. The silent pictures feel far less frenetic without the hard-edged angular graphics of sound effects over them, but also harder to decipher at some points, with fewer clues as to what the lines and shapes represent without the noises to help.

If Travel seems a little too abstract to get to grips with, there is a commentary by the author at the end of the book that helps decipher what you’re looking at. He adds information and observations for each page ranging from one sentence to whole paragraphs about what the images show, who the characters are and what they see. Some of his commentary is droll and not especially useful (“Page 18: the passenger in the second panel is carrying a comb in his pocket”) and he writes as if interpreting someone else’s dream, sometimes questioning the imagery and even speculating on what it might mean. Yet his notes will help you decipher the highly stylised forms that Yokoyama uses.

Further assistance comes from an introduction to this volume written by comics theorist Paul Karasik (writer of the excellent Paul Auster adaptation City of Glass) who advises the reader to “reconsider what plot is or can be” and locates the nature of this work in an experimental tradition that includes Jack Kirby and Bernard Krigstein.

Travel is just as challenging as Yokoyama’s first book but the rewards aren’t as clear cut. It’s not quite as compellingly bizarre as New Engineering, but it’s still a fascinating and brilliantly demanding work, to make you think (sometimes quite intensely) about how we represent the real world with lines and symbols, and what those lines themselves can mean. If you enjoyed his first book you will definitely enjoy this too.