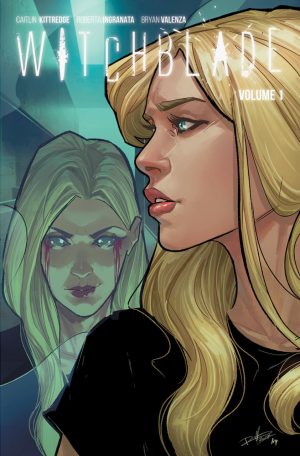

Review by Frank Plowright

Abby is a disgruntled army veteran who’s seen action in Afghanistan, but who’s been reluctant to address her repressed issues. Given what occurs when she finally attends a veterans’ therapy group, perhaps that was an advisable decision. She rapidly finds herself in the company of Doug, younger, but also damaged and capable of mentally moving objects with great finesse. Both are targets, but for whom?

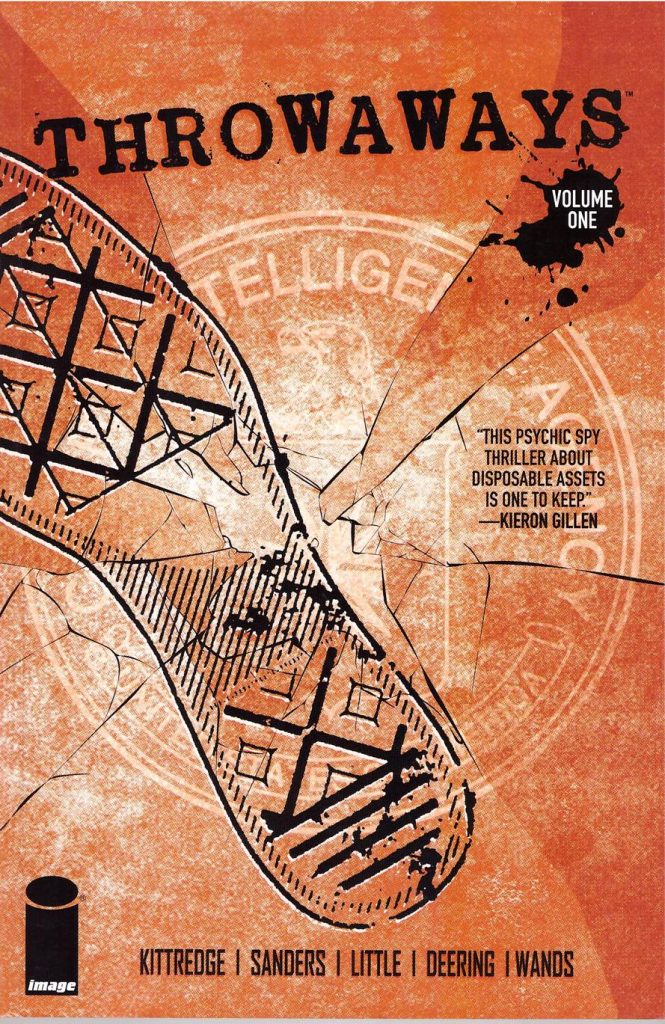

Caitlin Kittredge institutes a policy of keeping readers on their feet, and continues it throughout this first volume of Throwaways by blurring past and present, reality and hallucination, and shock and awe. She might not be best pleased with the back cover blurb disclosing more than she does over the first two chapters. Those end with the introduction of pallid Alice, also very capable and with considerable resources, and the primary cast is completed by Kimmie, revealed to the readers also to be a covert operative of some type, but believed by Dean just to be his girlfriend. After she’s explained as compromised, she becomes the nearest Throwaways provides to a sympathetic person.

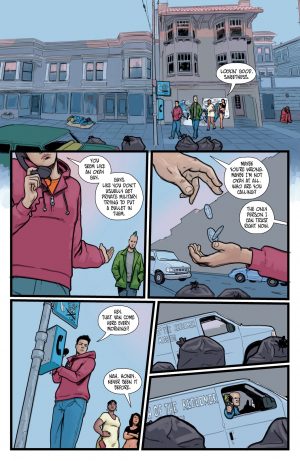

Steven Sanders was an experienced artist with a fair track record before beginning Throwaways. It’s therefore puzzling that on so many occasions his choreography of action scenes is confusing and features errors of people who shouldn’t be able to move to their new position in the time elapsing between panels, given what else is shown. There are also far too many pages where it seems no-one other than the cast members exist, which shouldn’t be the case for the locations used.

A vague sense of disappointment comes once the revelations coming rolling out, and it turns out that the basis for Throwaways isn’t too far removed from the us against the world of the X-Men, except here the powers have been genetically engineered. Gifted individuals are needed by a deep covert spin-off from the CIA, and much of the cast are of the entitled opinion that whatever their purpose it’s of ultimate importance, with any people obstructing it just unfortunate but justifiable victims. This ends justifying means approach doesn’t make for a likeable cast, and the people we are supposed to like have a default setting of surly that occasionally ramps up to livid. It’s partly due to what Kittredge explains as she goes along, but she hasn’t achieved the correct balance for narrative satisfaction. Perhaps volume two will rectify that.