Review by Roy Boyd

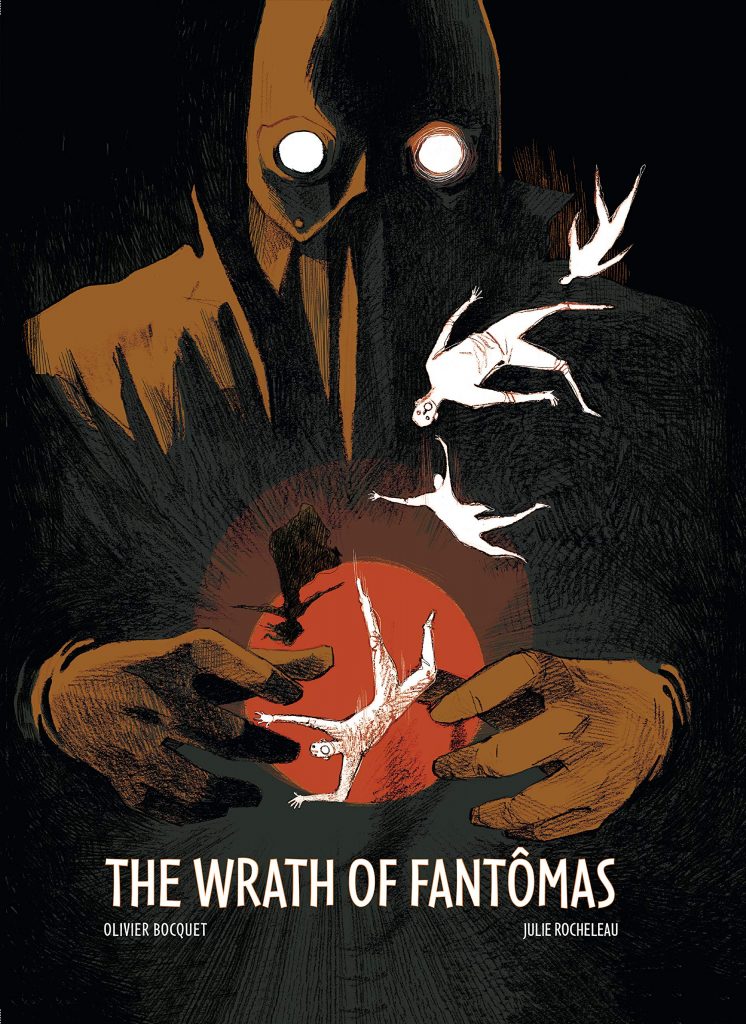

Fantômas, as sci-fi writer James Lovegrove informs us in this book’s introduction, may well be the original masked (anti) hero. The character first appeared in a series of French pulp novels, 32 books between 1911 and 1913 alone, that proved immensely popular, spawning movie serials, plays, paintings and much more. Interestingly, he also pre-dates by a couple of decades Lee Falk’s very similarly named Phantom, often cited as the first super-hero, although it must be said that the French are as bad as the Scots (your reviewer is one) for claims to have invented everything under the sun.

Olivier Bocquet’s plot pits Inspector Juve against his eponymous arch-nemesis. Fantômas is a criminal genius and master of disguise who claims to be fighting for the masses against their oppressors, though his fondness for the common man is called into question throughout the book. He’s absolutely bonkers: displaying sadistic tendencies and a wide streak of evil that would make the Joker blanch. In one memorable scene, his lover’s butler sparks his ire by speaking out of turn, so he rips the man’s tongue from his head with his bare hands (and later feeds it to his lover). Such delightful touches ensure this book deserves its mature readers label.

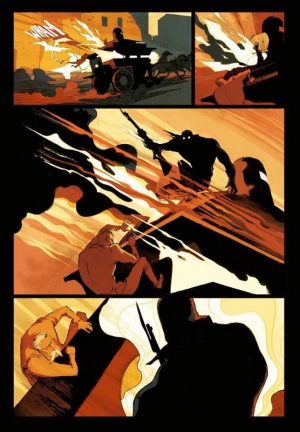

While Fantômas steals all the gold in Paris, Juve and his young assistant try their best to capture or kill him, leading to many violent and action packed encounters, some of them atop moving trains and the like. Bocquet sticks very close to the character’s pulp origins, although there are a few amusing modern references, including a ‘Duran Duran Phonographes’ shop, a droll take on Dirty Harry’s “most powerful handgun in the world” speech, and Juve channelling Danny Glover’s Murtaugh from Lethal Weapon when he says he’s “too old for this merde.” One assumes the “merde” remains un-translated to give the proceedings a Gallic flavour, as it’s certainly not out of consideration for the readers’ delicate sensibilities. The story also puts one in mind of Les Misérables, with Juve’s young assistant believing that Fantômas is responsible for the death of his mother. He wasn’t, although to give more away would be to risk spoiling the story.

Julie Rocheleau’s dynamic art is somewhat reminiscent of French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, eschewing clean lines in favour of something much looser and impressionistic. Although this can make it difficult at times to see exactly what’s happening to whom, this approach allows for some very striking and imaginative pictures. The book won a Joe Schuster award, and deservedly so. Both artist and writer equip themselves really well, and this volume is nicely self-contained, while still leaving ample opportunity for a sequel, in the best pulp tradition.