Review by Frank Plowright

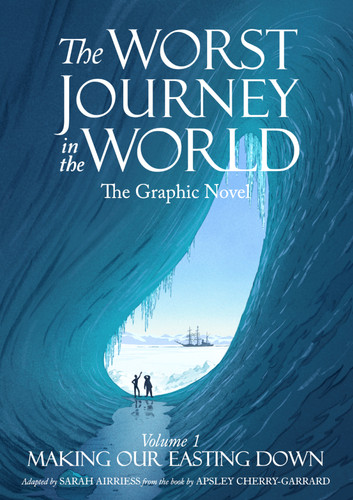

In 1910 Zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard joined Captain Robert Scott’s expedition to become the first humans to reach the South Pole. They reached their destination, but a few weeks after Norwegian explorer Roald Amudsen, and the return journey became a tragedy. Cherry-Garrard survived, though, and ten years later published his account of the trip, titling it The Worst Journey in the World. It remains in print a century later.

Sarah Airriess first came across it via a 2008 radio adaptation, and to say it became an obsession probably understates the case. Such is her dedication to accuracy, she actually visited Antarctica before beginning work on her graphic novel. Over fifty pages of panel by panel notes accompany her version, explaining creative decisions and supplying additional information, either detail or as provided by other accounts. She’s done Cherry-Garrard proud in creating a visual interpretation rich in character, detail and incident, although be warned that Making Our Easting Down relates just the journey to Antarctica on the Terra Nova, a former whaling vessel.

Wherever possible Airriess quotes from Cherry Garrard’s text, noticeable when the expedition crew are introduced, and she’s mindful of generating little dialogue, which is obviously assumed, and primarily used to contract explanations. As she’s both adaptor and artist she’s able to convey much information without words.

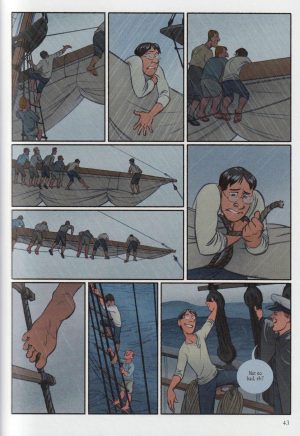

The art is excellent throughout, with storytelling clarity prioritised, which isn’t at the cost of detail. Just because drawings of boats occupy a single panel and are seen from distance, doesn’t diminish the fixtures and fittings visible. When a topic needs in-story explanation, astoundingly neat diagrams or montages are supplied. Because this volume is a long sea journey it’s punctuated by scenes of sunshine and, surprisingly, by the tourist stopovers. Life aboard a ship is related in considerable detail, educating as to the various tasks involved in the day to day running. The sample art details the danger involved in securing sails when they’re not needed. A considerable cast occupy the Terra Nova, and Airriess distinguishes them. However, they also betray her background in children’s animation, reactions being occasionally exaggerated too far, and mouths agape even when not shouting across ship in stormy seas.

If they weren’t already aware of what awaited in Antarctica the crew are given a taster of raw nature as the ship is struck by a storm on the way from New Zealand. As drawn by Airriess, it’s terrifying, the threat to life emphasised, as is the bravery in coping with the conditions. After the losses had been totted up, none human, Cherry-Garrard wistfully notes in his diary that on Monday night he’d been dancing in Port Chalmers.

By late 1910 the crew had reached the moving pack ice surrounding the main Antarctic continent, and they’d not see civilisation again for more than a year. Airriess ends with the dawn of 1911 and the crew finally sighting land. To be continued in Volume Two.

Perhaps you’ve never considered Antarctic exploration a topic of interest. Airriess doesn’t care, and her skill and enthusiasm supplies a first rate historical adventure anyone can enjoy.