Review by Frank Plowright

Every now and then an ambitious wrong’un with access to most influential levels of Trigan society features, and so it is with the pilot Vella, owing considerable amounts of money to a gangster, and willing to subject himself to a process that its devisor considers utterly evil. Chief scientist Peric is being made to exaggerate for dramatic purposes near the end of a two page episode, but ‘The Hydro Man’ is the nearest The Trigan Empire comes to involving super powers. Vella becomes able to transform himself into water and then restore his human form, giving him access to otherwise secure places. It’s in passing, but Mike Butterworth provides a chilling reflection of real world politics where allies have weapons aimed at each other, and it’s another story that’s rapidly wrapped up. That was also evident in The Prisoner of Zerss, and it seems by the early 1970s Butterworth had settled on between eight and twelve weeks of continuity as the ideal story length, although that would reduce slightly as the decade continued.

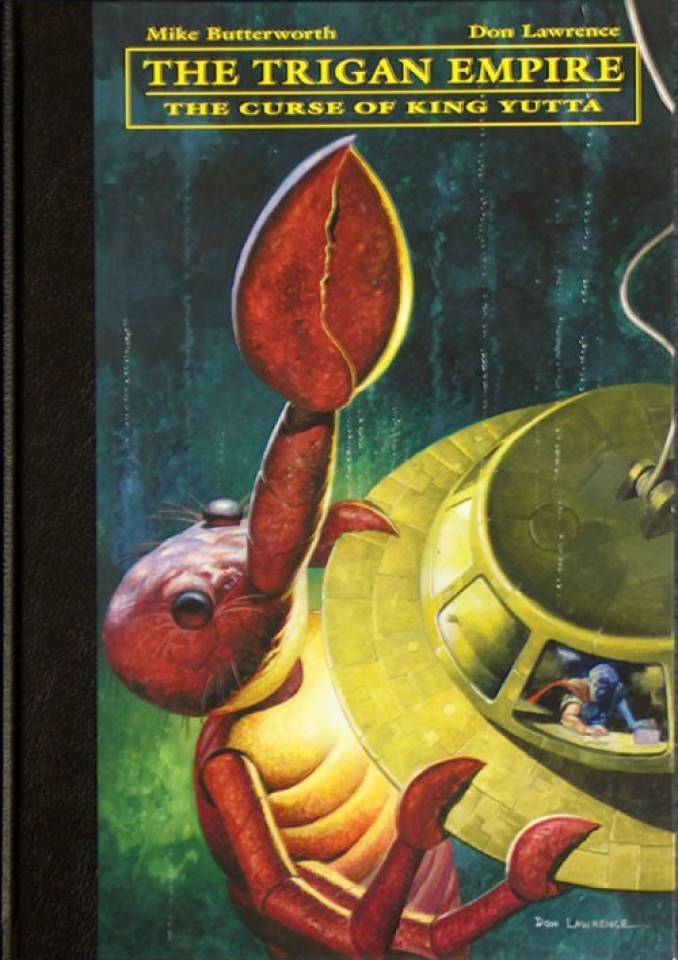

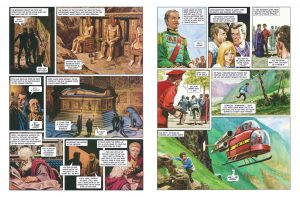

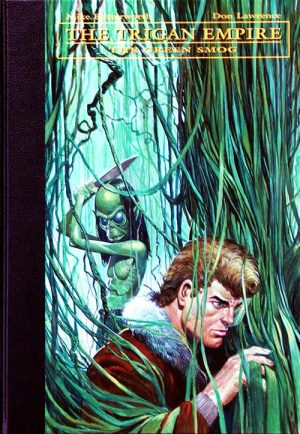

Both Butterworth and Don Lawrence were extremely capable of telling a complete thrilling story in twenty pages, and the benefit of regular switches rather than longer epics was Lawrence being given something new to draw with greater frequency. The title story switches from the Egyptian style culture of the sample art to the frankly bonkers monster of the cover, which is only seen briefly. The former was no doubt spurred by the heavily publicised 1972 Tutankhamun exhibition at the British museum, and for the second consecutive volume the title story is also the weakest, a rambling tale with Lawrence’s mummy disappointingly tame.

Lawrence loved illustrating a military man with a well-waxed moustache, a throwback to an earlier era even in the 1970s. Another features adorning Marshall Ossan, would-be overthrower of the empire in ‘The Lost Years’. Butterworth cooks up a nice conceit for events by having someone visit the future, then attempting to prevent what he’s seen from ever occurring. While Lawrence’s layout skills remain intact, parts of this story have the look of another hand. The faces are less defined on some pages and the poses stiffer, but other pages are sumptuous, and as seen on the sample, Lawrence sneaks in a cameo for Carrie, whose adventures he was illustrating for men’s magazine Mayfair at the time. This is a great story, easily the best in this book, a refined variation on the theme of military officers with ambitions of ruling that keeps the suspense until the end.

So does ‘Journey to Orcadia’, Butterworth’s version of sci-fi classic The Incredible Shrinking Man, with Emperor Trigo becoming ever smaller. As Steve Holland’s introduction notes, he’s fortunate his pants shrink along with him. Lawrence illustrates the threats sumptuously, and if the parallel plot of the public rioting because their Emperor is absent is never quite as convincing, it does prove a viable counterpoint.

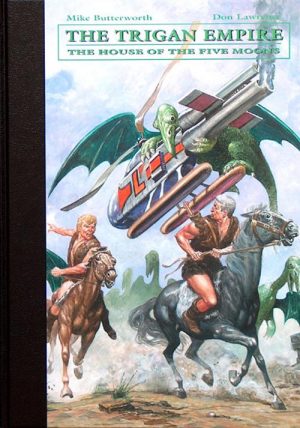

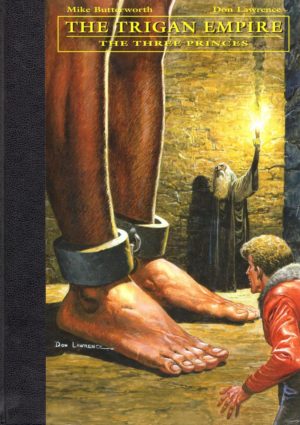

These oversized hardcover collections continue with The House of Five Moons, although it should be stressed that as continuity is almost entirely absent from the series, any volume can be read independently. Most of these stories are also included in the third standard sized paperback Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire.