Review by Graham Johnstone

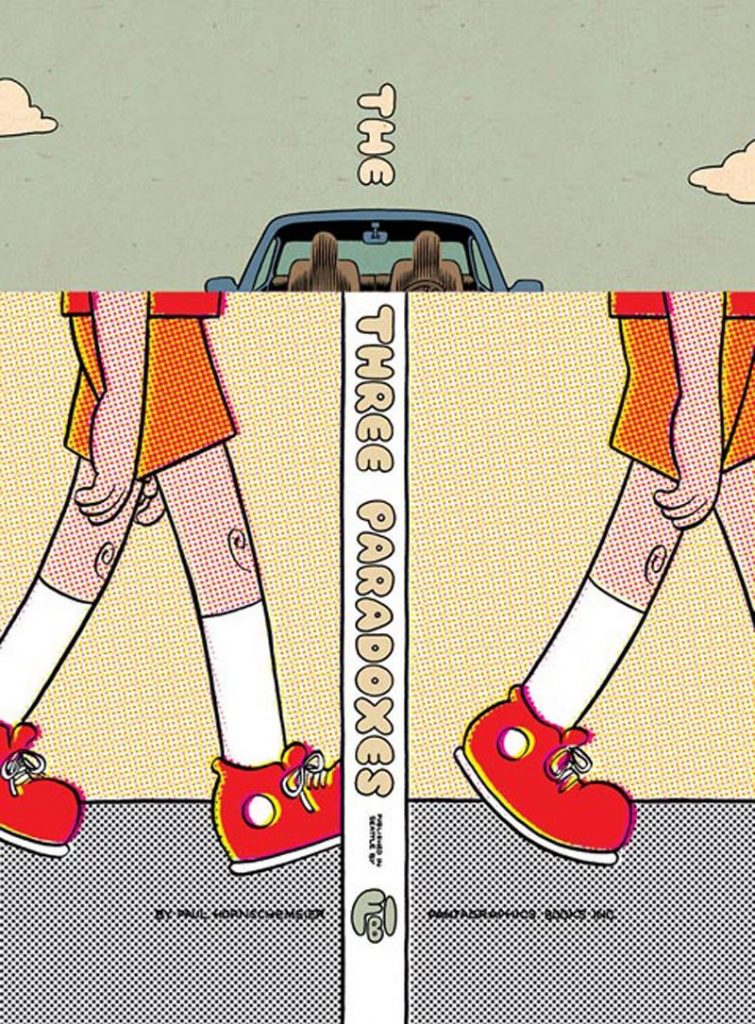

The Three Paradoxes are credited to ancient Greek philosopher Zeno. He imagined time as a series of frozen ‘moments’, with movement therefore an illusion. That could be a description of comics, suggesting the appeal for Paul Hornschemeier, the creator of philosophical and formalist comics collected in Let Us Be Perfectly Clear.

Hornschemeier combines several narrative strands. In a frame story, author avatar Paul visits his Ohio hometown, drawn into his past while contemplating his romantic future. He’s distracted by his work-in-progress comic ‘Paul and the Magic Pencil’, about a toddler walking alone into the woods. ‘Summer School’ involves the misadventures of an older child Paul, and ‘The Scar’ involves teenage boys, again in a wood, and a terrible accident. Finally ‘Zeno and his Friends’ has the philosopher presenting his ideas, including that of a journey being cut in half infinitely, until it becomes impossible to reach the destination. This prompts reconsideration of the preceding material. The perils escalate with the age of Paul’s avatars, teasing what awaits adult Paul.

These narrative strands are elegantly woven. The book opens with Paul’s pencilled pages about toddler Paul, and cuts to adult Paul trying to write the next line, then a panel of Paul’s comic with an empty word balloon (pictured), and back to Paul wondering, Zeno-like, if his comic is “going anywhere”. As adult Paul walks with his father, his work-in-progress encroaches on his mind, first in visual ‘thinks balloons’, then intercut panels, and his thoughts obscuring his father’s word balloons. Paul photographing locations of the ‘Summer School’ prompts flashbacks to experiences there. Adult Paul notices the boy with ‘The Scar’, triggering his memory of that story, and Paul’s resulting frozen moment prompts thoughts of the paradoxes. Zeno himself is then introduced, to explain the paradoxes playing out in the preceding pages. Such elegant transitions make an ambitious book flow well.

Each strand is stylistically different, specifically in higher or lower definition versions of (American) comics’ classic black lines with flat colours. Adult Paul’s visit home (pictured, right) is the most high definition; ‘The Scar’ has a cruder 1970s inking and palette; the toddler Paul comic is in cute cartoon style (pictured left); and, ‘Summer School’ resembles the crudest kids comics with exaggerated Ben-Day dots. These different approaches distinguish different strands, with their levels of definition also signifying their distance from present reality, in time, and so in fidelity of memory.

Hornschemeier delights in metafictional references to the methodologies of comics generally (the pastiches of period styles and production), and the creation of this specific book. For example, we see ‘real Paul’ taking a reference photo of his father (‘looking at the camera’), foregrounding it’s use in creating that drawing. The cartooned ‘Paul and the Magic Pencil’ is in the ‘non-photo blue’ pencil technique, so revealing the guidelines, mistakes, and imperfect erasures – usually unseen.

The resulting book transcends the paradoxes, for a poetic exploration of time and movement, both literal and figurative. There are powerful human stories here, encompassing childhood terrors, teenage accidents, and adult dilemmas. Yet, analysing the book is like Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise, we can run and get forever closer without actually catching up. The ‘Magic Pencil’ raises the idea of erasability: with all the foreshadowing of death on his journey – did something go wrong that ‘Paul’ has erased, or does the idea of erasability empower him to move forward with the new woman… ?

As with Zeno’s paradoxes, there may never be a definitive answer, but readers reaching the book’s end are left with a lingering, intriguing conundrum.