Review by Frank Plowright

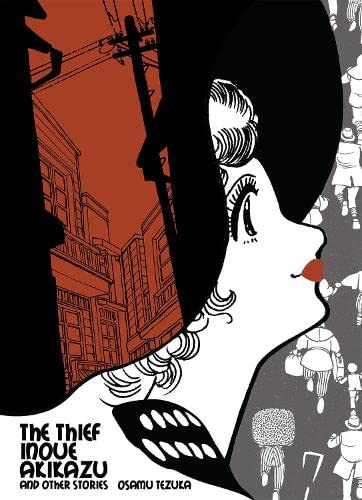

The Thief Inoue and Other Stories collects five graphic novellas produced by Osamu Tezuka, four in 1972 and 1973, and the title story from 1979. As in other collections of his assorted work, they’re themed, in this instance around crime.

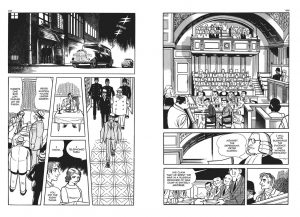

A process Tezuka frequently used was to create his own story around a name or incident that grabbed his attention, yet for the opening tale of Peter Kürten he sticks closely to the facts. Kürten was dubbed “the Düsseldorf Vampire” by the press when he committed his crimes in the late 1920s, and although dramatised via staging, dialogue and cinematic lighting, Tezuka presents broadly what happened. He notes Kürten’s wife having a murder conviction, his trade union activities, and the strangeness of his trial. It has adult themes from the start, and this also applies to other stories.

It’s been mentioned in other reviews of Tezuka’s work, but it’s worth reiterating how his output is simply staggering, even allowing for the employment of studio assistants. This content is only short stories in the sense of each being complete in themselves. Each occupies around sixty pages. While producing them he was also serialising Ayako, Barbara, Buddha, Lion Books and Phoenix, and about to begin work on Black Jack.

That may account for the relative slimness of the stories following Kürten’s. An obsessed and broadly caricatured businessman earns what’s coming to him, a paranoid medieval Lord acquires a double and a woman hankers for revenge on an unfaithful husband. In each case there’s little emotional depth, and rape scenes feature in most, Tezuka uncharacteristically resorting to cheap shock to sell them. They’re all very nicely drawn, though.

At almost a hundred pages, the title story, also referred to as ‘The Mountain of Fire’, is the best. The puzzlingly misleading cover leads one to believe that Inoue is a woman, which isn’t the case. It’s a big, violent man, who ends up in the village of Sobetsu in 1943 just as a series of earthquakes affect the area. Inoue is appointed by the local postmaster to aid a survey that the postmaster hopes could save the village. Inoue just sees his new status as an opportunity to ply his thieving trade, the papers giving him official access to properties.

Tezuka visited a volcanic area shortly after an eruption to cement the artistic authenticity, and the scenes of devastation, and what’s required to traverse areas where the landscape has changed are very convincing. It’s a tale of redemption in one respect, but not the expected redemption, and all the better for its unpredictability. Inoue himself is a peculiar fictional insertion into what’s otherwise recognition of surveyor Mimatsu Masao, on whose memoirs the story is based. Perhaps Tezuka felt a violent thug would distract from what could otherwise be dry material. It’s not anywhere near Tezuka’s best overall, but is the saving grace of this collection, which is otherwise flawed and trivial.