Review by Frank Plowright

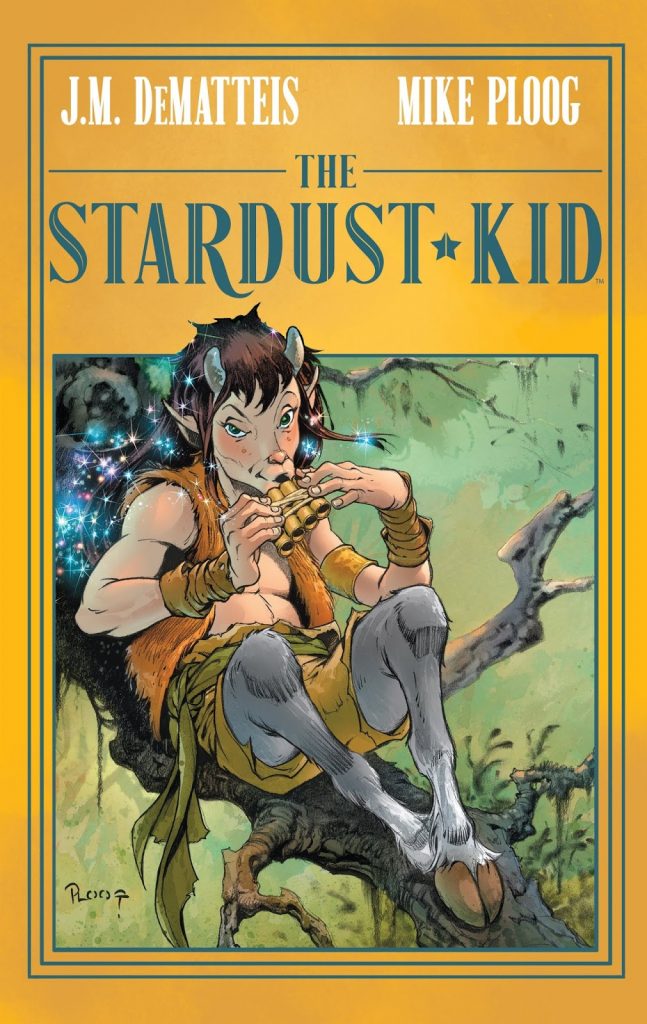

A heartwarming introduction from writer J.M. DeMatteis reveals how he first conceived The Stardust Kid as a way of mythologising adventures of his then young son. When it finally saw print almost thirty years later his son was the book’s editor.

The Stardust Kid is Paul Brightfield, thirteen, best friend of Cody DiMarco, almost thirteen, concern to Cody’s mother for instinctual reasons she’s unable to verbalise, and with good reason. He’s magical, an aggregation of dreams made real, and in various forms has always known Cody.

His introduction makes clear how close to DeMatteis’ heart The Stardust Kid is, a project he’s wanted to see the light of day in various forms for so long, and in one way he’s been blessed by delay as it enabled him to hook up with Mike Ploog as artist. Ploog’s cartooning is child-friendly, oozes charm and has the benefit of decades of experience behind it, ensuring every page is crafted beautifully by an artist who remains at his peak. He knows how to induce a shiver without terrifying and every character has a life to them, whether you’d want to know them personally or not. The Stardust Kid veers between traditional comics and illustrations with captions, and this format enables Ploog to shine even more than usual, with some beautiful full page portraits. His lumpy tree beasts stand out as wonderful creations.

The story itself is also wonderful, imaginative and unpredictable. It’s the well trodden path of a few children completely out of their depth desperate to do the right thing against all the odds, but with enough originality about their circumstances to ensure The Stardust Kid is thrilling. We feel for Paul, whose confusion about growing up is well handled by DeMatteis, and the confusion among his friends. However, the way DeMatteis chooses to tell the story, and has chosen to tell others in the past, is via an all-knowing narrative voice, and that narrator can be smug and irritating. All too often there are diversions into unnecessary explanations about shifts of tense, or reiterations of a lack of belief in time, eccentricities that have little bearing on events. There are similarities to The Princess Bride, where narration worked so well, and this narration eventually has a purpose, but when everything else is so endearing, it’s intrusive and misjudged.

If you choose to see it that way DeMatteis has crafted a metaphor for growing up, advocating that sometimes you have to face the unknown and you’ll come out the better for it. Don’t bother with that sort of analysis, though, and there’s still a thoroughly engaging fable that would have been better with less narration.