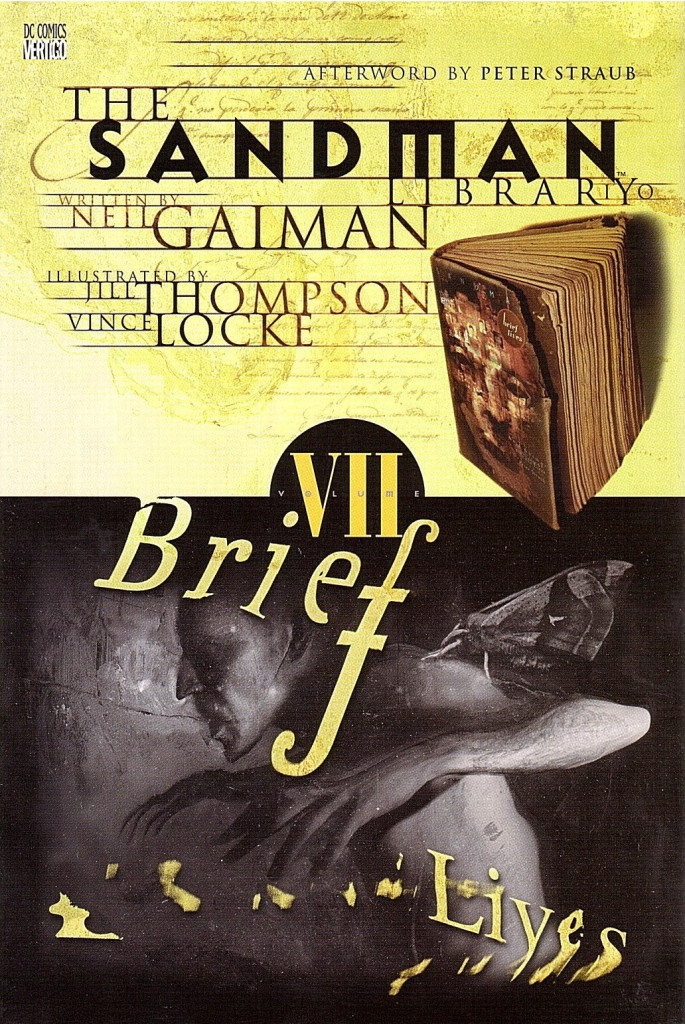

Review by Karl Verhoven

Much of Sandman beyond the earliest two volumes has presented Dream in passing, as the deus ex machina, the pithy observer, or the distanced icon, but in Brief Lives he takes a central role. Within several characters offer their assessment of Morpheus: “A romantic fool. Self-pitying, but with a certain amount of personal charm.” or “He’s a good guy, y’know, but he overreacts. One little thing goes wrong and he acts like the sky is falling.” The latter is intended as an ironic counterpoint, but is nonetheless valid.

Delirium decides the time has come to locate their missing brother Destruction, and being at somewhat of a loose end, Dream decides to accompany her. This is one long shaggy dog tale, the joy being entirely in the telling, a meta-fictional point made within, but for maximum enjoyment much will depend on whether Gaiman’s characterisation of Delirium as a constantly addled naif is perceived as sympathetic and relevant to her representation. In small doses, she’s a diversion, but as a lead character she can strain the patience.

Countering this is that Brief Lives is the most ambitious Sandman tale of the original run. Gaiman delves right into the myth he’s created, and emerges with his hands dirty, having deconstructed much of the foundation. It’s a dense and complex exploration of what the Endless represent, how they can change and whether in another context the title applies as much to them as humanity. It’s certainly instrumental in setting up how the series progresses, and is the first indication of that, although in extremely oblique fashion. The centrepiece conversation on a Greek island is masterfully constructed, and for the first time Dream is portrayed as somewhat out of his depth in the presence of someone with far greater self-awareness and a less insular view.

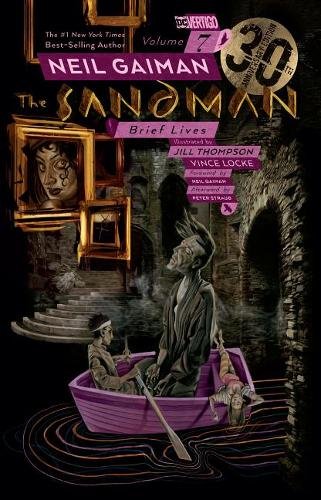

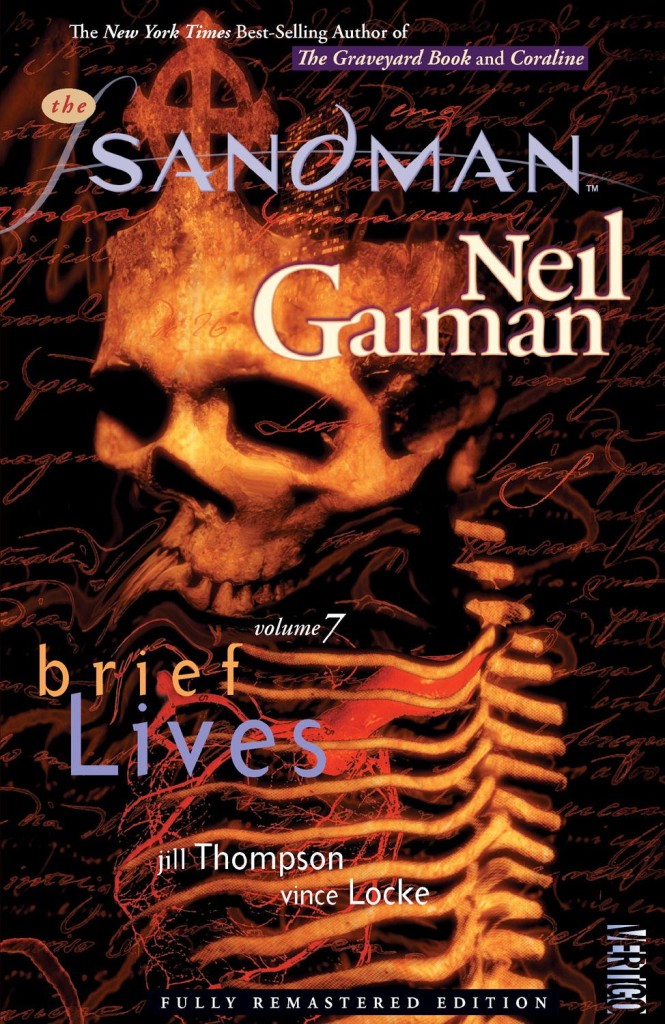

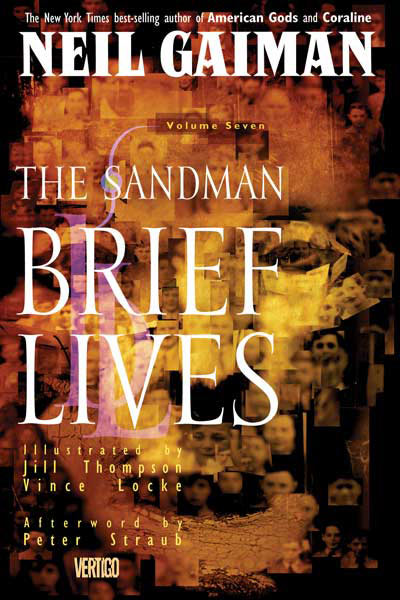

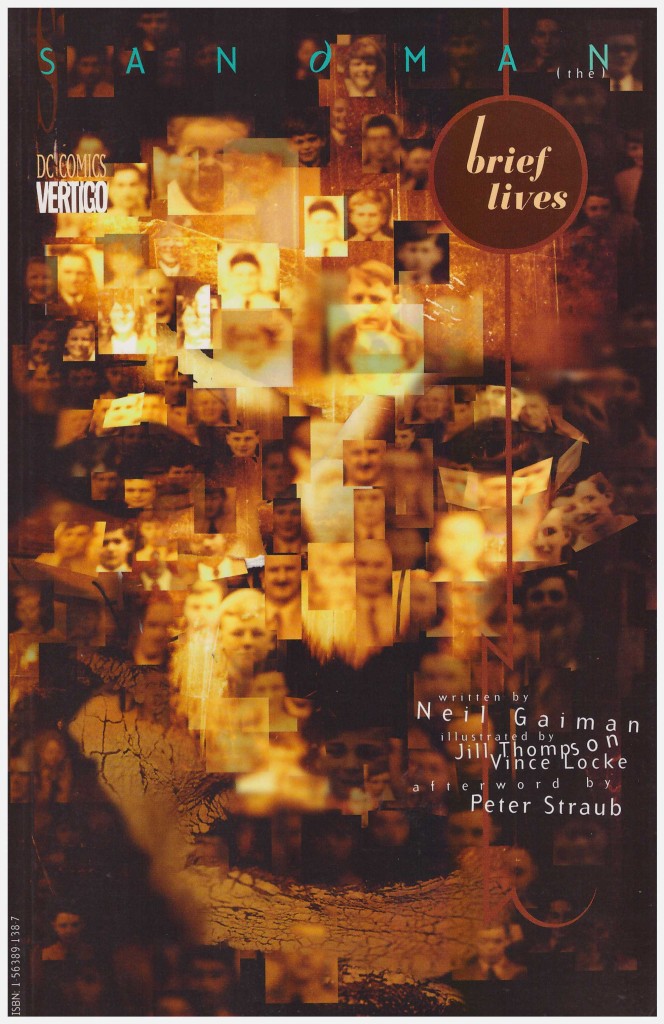

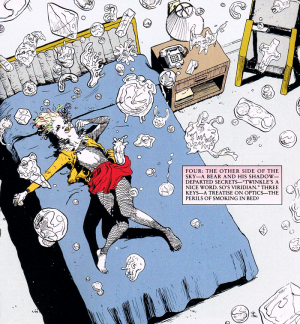

Jill Thompson’s pencils as inked by Vince Locke are a fine combination. She doesn’t shy from detail, nor from several gruesome scenes, even to the point of drawing her own likeness as a potentially doomed character. There’s a fine emotional intelligence to the art, and while Delirium may be a twee irritant in concentrated doses, Thompson’s portrayal of her casual eccentricity, variable moods and constantly shifting appearance is fascinating.

A consistent delight of the best Sandman material is the way Gaiman will just drop the unexpected consideration into a caption, seemingly in passing: “There are for example less than ten thousand humanoid individuals alive on this planet today who have personal memories of the saber-toothed tiger”. Parse that! And he makes a special distinction for “humanoid”. Immortality as a thread runs through the series and extends, now to the material presented, at least in terms of graphic novel history, and this is probably the best Sandman graphic novel.

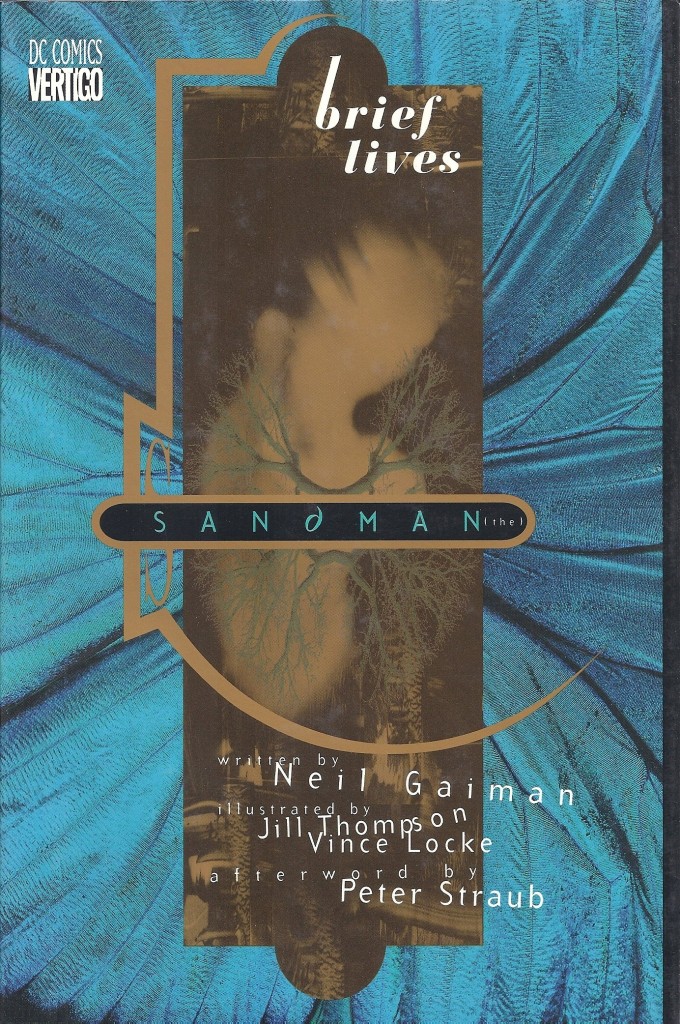

The content here has been re-mastered for volume three of Absolute Sandman, where it’s presented in an oversize format in a hardcover book and accompanying slipcase. Those re-mastered pages also appear in volume two of the bulky Sandman Omnibus, which also includes World’s End and The Kindly Ones. Volume three of The Annotated Sandman features this accompanied by Gaiman’s inspirations and references on a page by page, and sometimes panel by panel basis. There the pages are in black and white.

For those on a budget whose preferred choice is the traditional paperback format, the production tinkering is relatively minimal, so the choice amounts to preference regarding the original colouring or the updated palette in post 2010 editions.