Review by Ian Keogh

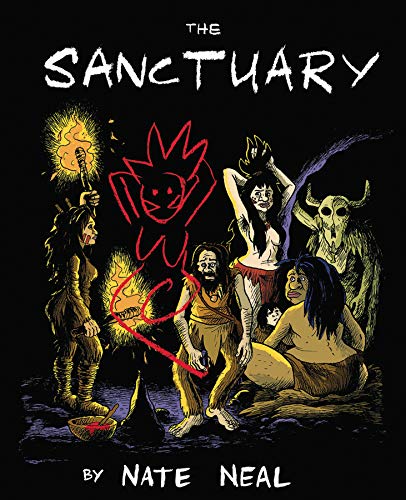

The Sanctuary is a drama set in Paleolithic times supplied without the use of recognisable dialogue to comment on the place of art in society.

The central figure is a thin artistic type, not greatly valued by a tribe whose survival depends on the bravery of hunters bringing their killings to feed the cave-dwelling collective. Their kills are recorded by the cave painter. His only understanding comes from the former alpha male whose status has been reduced by losing an arm. To the current alpha male, and those who suck up to him, the artist is a barely tolerated deadweight, consigned to his own solitary area deep in the cave system and perpetually hungry. His only use to the community is to record the glory of a successful kill, yet in his own hidden area he draws his own stories on the cave walls.

While no-one knows exactly how humans lived in caves several thousand millennia ago, there’s no doubt that basic survival from year to year was the priority. Nate Neal, therefore, makes no revisionist concessions to life in a far from ideal world. The brutal reality is that the most powerful can do what they like, and do, with that behaviour trickling down the pecking order. That feeds into change for the artist, when a woman is traded by a neighbouring tribe.

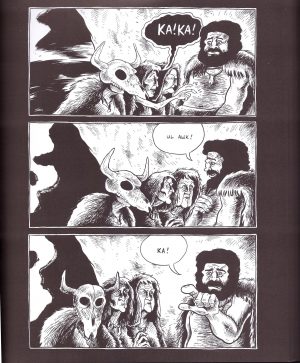

Neal draws everything simply, necessary for clarity as the dialogue is largely absent, and as so much is set within the caves there’s far more black than white, the darkness accentuated by having the pages black also. Atmosphere is important, what illumination there is coming from fires, and Neal using that for effective abstract panels with brief flashes of light. Because there’s no immediately comprehensible dialogue, posture and expressions become extremely important, and Neal ensures the story is understood without the dialogue.

Online reviews mention deeper understanding from repeated reading, and it’s apparently possible to decode the simple words used by the cave people, although given the time involved, the likelihood is that few readers will make the effort. Likewise, while The Sanctuary definitely comments on the value of art, it’s possible to read a more specific allegory about comics that may or may not have been intended. Ultimately, though, the truth of what the artist records does bring about change, reflection prompting progress, although also uncertainty. Read The Sanctuary twice as some online commentators advise and perhaps there is even greater meaning, but just the single reading is satisfying for a graphic novel unlike any you’re likely to have encountered before.