Review by Ian Keogh

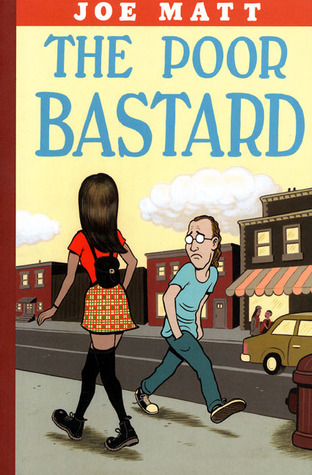

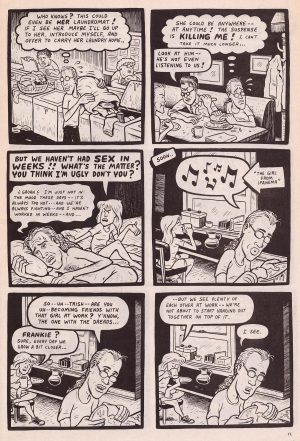

With The Poor Bastard Joe Matt moved from ornately designed one page autobiographical and observational humour strips to longer form autobiography, and it’s an awkward change. As with all autobiography, only the creator knows the full extent of the truth, but Matt begins by presenting a supportive and caring girlfriend whose insecurities he barely bothers to assuage, while casting himself as a tight-fisted misanthrope who considers punching his girlfriend is teaching her a lesson. It’s not mitigated by a later disclosure of theirs, on occasion, being a violent relationship. By admitting assault less than ten pages in, the phrase ‘warts and all’ somehow seems a woefully inadequate description. Matt follows that with pages of pitifully attempting to cop-off with his girlfriend’s workmate, and never mind the pornography addiction. The wonder is that girlfriend Trish stays, because if he has likeable qualities few of them are displayed.

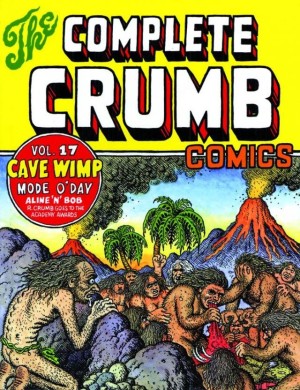

In terms of style Matt very much follows Robert Crumb’s lead with a compulsive confessional approach laying his inner thoughts bare in the full knowledge that they cast him as resolutely unpleasant. The fascination is in reading about Matt behaving in appalling fashion while justifying it with speeches about being accepted for the way he is, yet being entirely unable to apply that standard to anyone else. This alternates with self-pity mode, whining about minor elements of his life that don’t go to plan. There is a self-awareness, and a Jiminy Cricket form of conscience in the presence of fellow cartoonist Seth, portrayed here as constantly calling Matt on his wretched double standards.

This material isn’t as engaging as the shorter strips in Peepshow. Given more space, Matt becomes more indulgent, and the comedy is repetitive, originating almost entirely in admonishment or Matt’s cartoon-like scheming being undone by fate. It’s taken over four years, but Trish finally dumps Matt, and the remainder of the book vacillates between somehow never very convincing realisations that perhaps he ought to have made an effort, solo furtive beneath the sheets fumbling, and assorted attempts to begin a new relationship. These are half-hearted and fantasy led, although they result in such a convenient pay off it induces speculation about where fact and fantasy intersect. Has this been contrived for inclusion in the comics on the chance Trish might see them?

Ultimately it’s the cartooning that’s the most memorable aspect of this ironically titled graphic novel. There’s barely a panel in which he doesn’t feature, and Matt’s assorted self-portraits range from the grinning huckster to the despondent romeo with plenty of cum faces along the way. His tidy line is expressive and for a man who portrays himself skimping so much in real life, there’s no shortage of detail to the individual panels.

It’s difficult to locate a single redeeming feature about Matt as he presents himself, and the letters pages in the original comics gathered here contained one succinct note of thanks for making every other guy look good. The car crash persona doesn’t provide substance enough to sustain The Poor Bastard, and perhaps aware of that Matt returns to childhood for the subsequent Fair Weather.