Review by Ian Keogh

Many people know The Picture of Dorian Gray’s central premise, but have little further knowledge of Oscar Wilde’s sole novel. It’s strange to think that in more repressed times it was accorded a poor reception. Whimsical, allegorical, and with homoerotic undertones (as far as was permitted in 1890) it’s a thoroughly entertaining gothic pastiche, a fountain of witty epigrams and a plea for decadent indulgence.

We first meet Dorian Gray through the eyes of others, obsessed painter Basil Hallward, and his friend Henry Wooton, whose judgemental opinions of character are based on the portrait Basil is on the verge of completing. Wooton serves as Wilde’s intrusion into his novel, and Roy Thomas packs the opening chapter with his caustic brilliance, surprising with how many sayings from it have trickled down into common usage. Thomas does fudge a little, moving them around in order for a smoother overall read, but better that than omitting any.

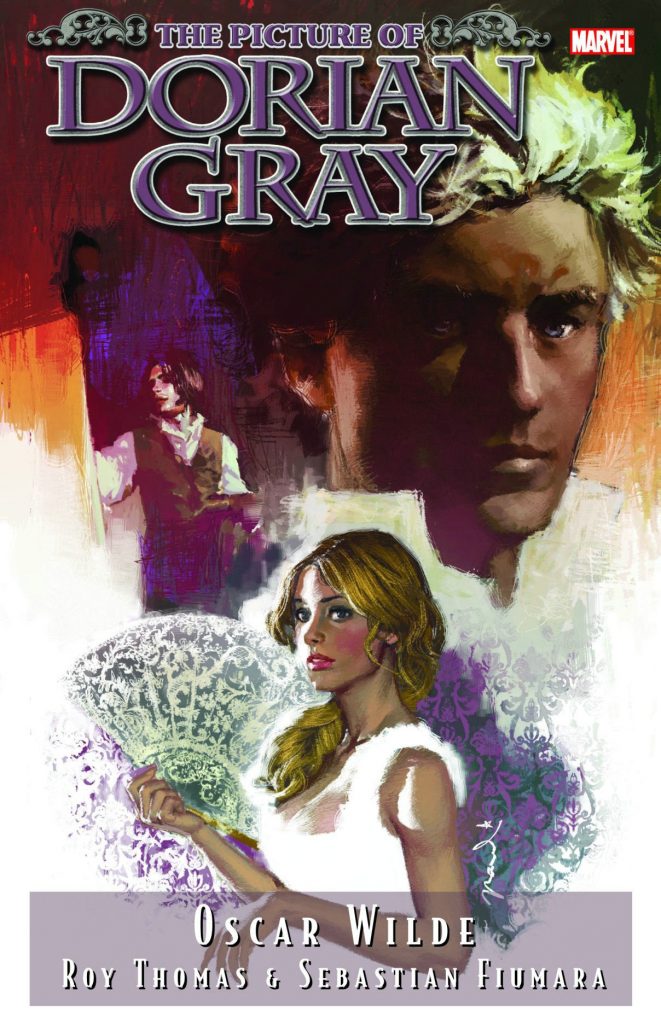

In a story hinging so much on a portrait of beauty, with a side serving of aesthetic discussion, an artist not up to an idealised presentation would sink the adaptation. Thankfully Sebastian Fiumara has a fine art delicacy when it comes to displaying personality. The cast are meant to be desirable men, and Fiumara ensures they are. Unfortunately he falls down with the picture of the title. It’s supposed to be the reflection of Gray’s corrupt soul, but the first time we see it, instead of being shocked we see just a slightly older looking man with a sardonic smile, the kind of portrait John Constantine would kill for. Fiumara’s final attempt is closer to the real deal, and his illustrations of the contrasting Victorian opulence and squalor are suitably decorative and sordid respectively.

It’s a fair way through the story before we see how substantially the Dorian Gray of the picture has altered, the result of an impassioned plea vocalised then forgotten in the opening chapter and subsequent debauchery. By then Wilde and Thomas have introduced us to Wooton and Gray’s circumstances, and to actress Sibyl Vane, by no coincidence specialising in tragic roles, and taken us through several years of scurrilous rumour and objectionable behaviour.

For all the iconoclasm it’s to be speculated whether the weak, moralising toward the end was Wilde’s attempted method of forestalling critics, but it builds toward a great gothic climax during which Thomas and Fiumara stretch out the revelation well. Overall the graphic novel is a spirited and engaging read undiminished by being visualised. Immerse yourself with confidence.