Review by Ian Keogh

As The Encyclopedia of Early Earth proved, Isabel Greenberg is a natural storyteller who invests her tales of human drama with a mythical and sometimes mystical quality. She begins The One Hundred Nights of Hero with an alternative version of the creation myth, replacing the old bearded god with a young girl creating humanity as a plaything to be observed for enjoyment, who is supplanted by her father. It expands on the world of Early Earth and contextualises the humans then explored over six stories, set across various cultures and periods of history. These are wrapped in a second framing sequence. Just as Scheherezade in Arabian Nights postponed her execution by spinning compelling stories, so Cherry delays her would-be suitor’s advances by having her maid Hero tell equally entrancing tales.

One story leads into the next as a succession of narrators beguile. What stories they are! Dramatic, poignant, tragic, plumbing depths and rising to crescendos while all the time keeping invention at the forefront. Some tales have a slight familiarity, such as the princesses escaping to dance at night, but Greenberg weaves her own interpretations. She introduces concepts we recognise, such as trees with man-made objects hanging from the branches, which she names Thing Trees, and gives them new and deeper meanings, while also harkening back to the conveniences of myths. She’ll sometimes highlight these with a sardonic footnote, but they’re perfectly legitimate in context, and fit her application of modern language to ancient forms of storytelling.

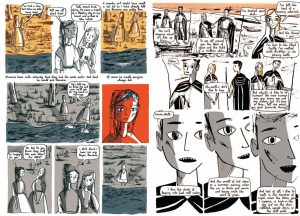

There’s a sketchiness and simplicity to Greenberg’s art accompanied by people drawn as if from ancient frescoes, but also great depth to the design and an exceptional provision of nature. It’s jagged, and often sparse, but very thoughtful in the small details. The same applies to the people, who at first glance seem crudely drawn, but the emotional resonance is there in posture and glances.

Small details dropped along the way show Greenberg well aware of the structure and boundaries of the world she’s creating. The stories are united by the city of Migdal Bavel and the bird god people worship. A strong theme throughout is women as second class citizens, whether cosseted for alleged protective purposes or plain subjugated by men. Any of them daring to question the validity of such arbitrary rules as women being prevented from reading suffer, and although there are some happy ever afters, don’t expect it all the time.

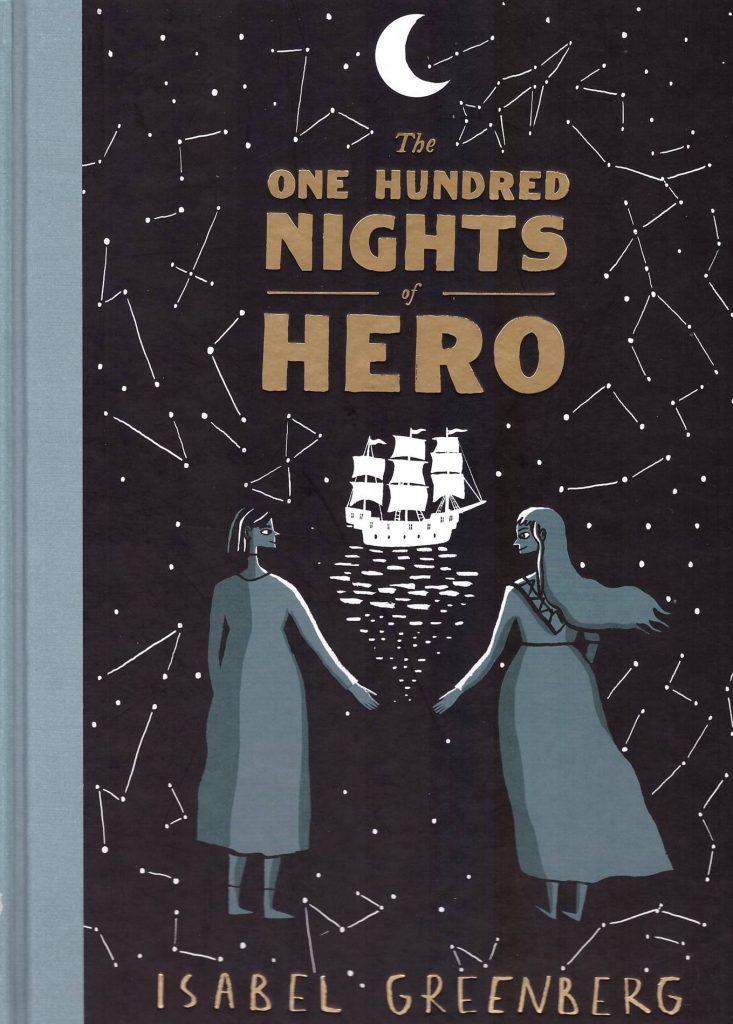

The One Hundred Nights of Hero is a constant joy and designed to resemble the storybooks of the early 20th century, being an oversized hardcover in cloth binding and pasted on cover illustration.