Review by Jack Kibble-White

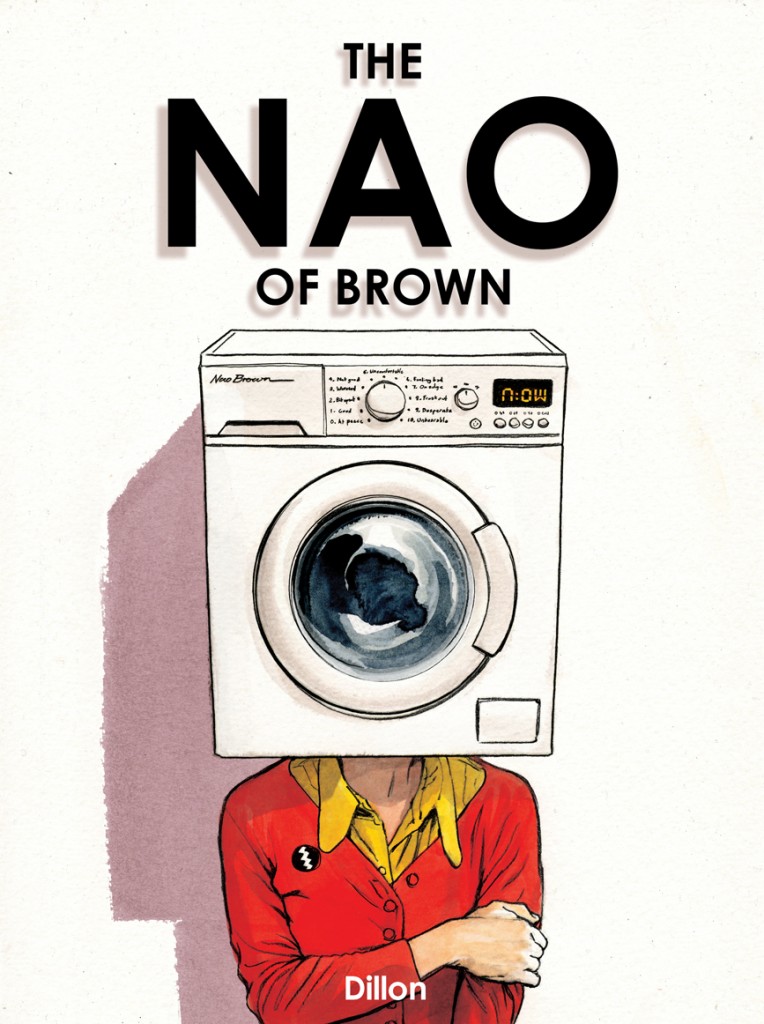

The front cover for The Nao of Brown really doesn’t do the job. It consists of a simple portrait, albeit with a washing machine filling the gap above the shoulders where a head should be. It makes for an arresting image, but it’s not in keeping with the subtle visual grammar of the rest of the book. The inset image on the inside leaf of a horse chestnut is far more appropriate.

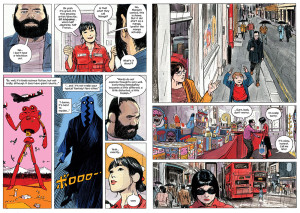

The Nao of Brown is a story that relies heavily on writer/artist Glyn Dillon’s ability to capture naturalistic body language. In movement, conversation and quiet contemplation, Dillon’s characters possess a physical authenticity that is extremely pleasing. The narrative follows OCD-suffering Nao Brown, as she seeks to conquer her obsessional behaviour and establish a meaningful relationship with Gregory, a washing machine repairman. Add to the mix Nao’s long-suffering platonic male friend, Steve, who is quietly and unrequitedly in love with her, and Dillon has constructed a romantic story with a familiar geometry.

The world of Nao – of cutesy toy shops, West London pubs, shared cultural reference points, copies of G2 used as makeshift fly swatters and the accepted importance of C90 mix tapes – can be quite off-putting, if you don’t wholesale buy into what feels like a very metropolitan set of values. Yet, it’s difficult not to be at least partially seduced by this story.

This is largely thanks to Dillon’s superb visual storytelling. Quite apart from his seemingly innate knack of understanding how human bodies and faces behave, his sense of pacing is immaculate, making a reasonably slight story a pleasure to read. Dillon’s style taps into European, rather than American influences, with his page layout’s resembling stalwart artists such as John Burns. You can imagine that had he been working some forty or so years ago, Dillon would have made a brilliant fist of drawing for TV tie-in comics, such as the British weekly Look-In.

So it’s Dillon the artist who wins out over Dillon the writer. Although he has a good ear for realistic-sounding dialogue, the motors that drive Nao, Gregory and Steve somehow lack that satisfying clunk of authenticity. Perhaps it’s that each one occupies an all too readily identifiable archetype, with Nao herself being a pretty close personification of a “pixie dream girl” – albeit one with barely controllable urges to inflict violence upon others. Dillon feels as if he’s writing from well within his comfort zone and it’s difficult not to conclude we are reading a cosy approximation of real life.

Still with pages and pages of gloriously confident ink and water colour images, there are far worse ways to spend a few hours than curled up within the restless mind of Nao Brown, even if it’s a mind you can’t wholly believe in.