Review by Frank Plowright

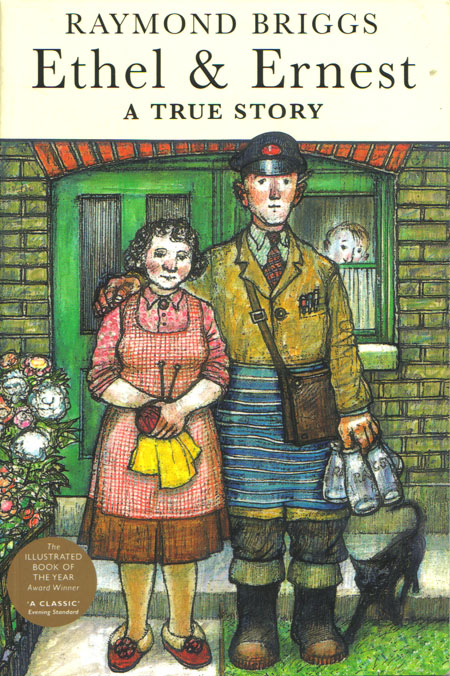

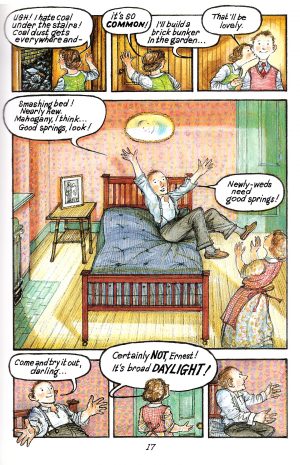

In the 1980s Raymond Briggs satirised elements of his parents’ characters in producing the all-ages Gentleman Jim and the bleak and adult When the Wind Blows. In 1998 he rectified this as Ernest and Ethel Briggs became the subject of this loving biography. It’s far more, though. It’s a fantastic repository of the vanished – costermongers, Victor McLaglen, didicois, guineas – and a glimpse into a byegone era where there was a wonder at the then luxury of the standard two up, two down terraced house. When public baths and outside toilets prevailed, Ernest works ceaselessly to upgrade the property long before DIY became standard.

Without filmed footage, it’s extremely difficult for any child to imagine who their parents were before they came of age, yet Briggs supplies a remarkable representation. When they meet, Ethel is employed as a maid for a pair of ageing war widows (or spinsters) and Ernest waves at her every morning as he cycles past on his way to work. Ernest enjoys his life as a milkman and is resolutely good-natured and optimistic, and Ethel loves him adoringly. It brings a tear to the eye. Really. For all the love and good cheer in the house, Briggs includes a very telling line when Ernest, reading a newspaper, notes the average family require £6 a week to stay above the poverty line. Neither he nor Ethel understand the term, but Ernest wistfully wishes he earned that much.

The longest section deals with ordinary life during World War II, the heartbreak of the young Briggs’ evacuation, the day to day deprivation and indignities, and the tragedy witnessed by Ernest on his rounds as a volunteer fireman. It’s a rare piercing of his resolutely good cheer.

Much praised in the 1980s, as The Snowman has become a national institution Briggs’ other work has rather fallen by the wayside, and that’s an enormous shame. It’s varied, beautifully drawn, amazingly emotional, and Ethel and Ernest proves he knows adults every bit as well as children. The best sequence of the Pixar film Up was the loving relationship detailed over the opening fifteen minutes, and Ethel and Ernest delivers exactly that blend of wistful and idealised love. There’s a broad streak of sentimentality, but, aware of this, Briggs always undercuts his narrative with a succession of intrusions, many involving himself as a youngster.

The way they’re portrayed by Briggs, his parents often failed to grasp how the world worked, but had a strong sense of right and wrong, and of political conviction. Progress largely passes them by, and they’re puzzled by and suspicious of the new, but this honesty never becomes ridicule. This is a heartfelt elegy. Would that we are all recalled so fondly.

A faithful 2016 film version with Briggs’ co-operation expands on many themes and anecdotes, also featuring new material. It doesn’t really add anything, however, and the extended focus on particular times to the curtailment of others disrupts the graphic novel’s careful balance.