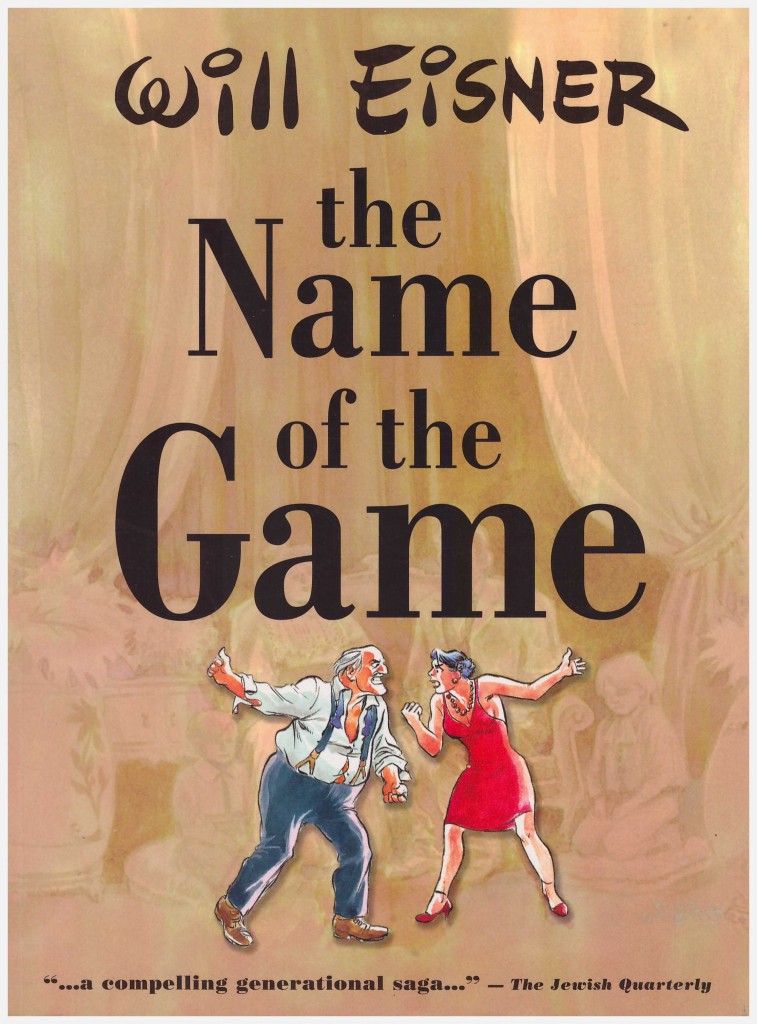

Review by Frank Plowright

This numbers among Will Eisner’s later graphic novels, and studies the old European tradition of a family acquiring greater social status through what’s perceived as a good marriage, and how this transferred to the USA via 19th and early 20th century immigration. In a society where anti-semitic prejudice was open and insidious, the Jewish community believed acceptance lay in maintaining the highest standards of social propriety. This topic was addressed far less savagely, in part, in Eisner’s preceding work Minor Miracles.

This generational epic spans a period of roughly eighty years from the 1880s onwards with the central focus being Conrad Arnheim. He’s spoiled and pampered as a child, when money could cover any indiscretion, so is totally unfit to run the family corset business in which he has no interest anyway. He maintains social status by frittering the family assets, is blessed with an anti-karmic run of good fortune, and as the decades progress prestige is maintained in a burgeoning society by reinforcing the hollow distinction of ‘old money’.

Eisner delivers a depressing portrait of ambitious wastrels who trade unscrupulously on the family name while caring little about those left ruined in their wake. It covers several generations, adapting well to the differing attitudes of youngsters, yet detailing how some are co-opted.

There’s a broad streak of discontent running though The Name of the Game, and Eisner based elements of the story on his wife’s family. This possibly contributes to characters lacking the depth of his other work. Conrad is a monstrous creation, selfish, self-entitled and too cynical to be in thrall to the family illusion, yet manipulating it for his needs, but even he has his moments of caricature. Abducting the daughter he discarded as an infant is one. His brother Alex never transcends caricature, portrayed as an ever more dissolute shambling wreck, while others are reliant on a single defining characteristic.

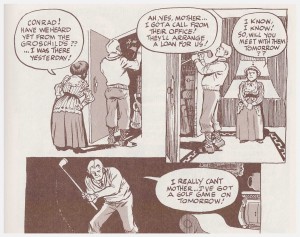

There has been no such thing as a bad Eisner story for fifty years, and this doesn’t break the run, but it’s uncomfortable reading with few likeable characters that emphatically answers any criticism that sentimentality underscores all Eisner’s work. Artistically, though, Eisner is on top of his game. His cast can be read without text, their posture and expression alone revealing them. Oddly, though, rather than relate his entire story in comic form, Eisner punctuates it with slabs of text covering the passage of time between important incidents or complex emotional issues. It’s a strange intrusion so near the end of a long career from a man who proselytised for the comic form his entire life.

This is collected along with the autobiographical To the Heart of the Storm and The Dreamer, within the larger Life, in Pictures.