Review by Frank Plowright

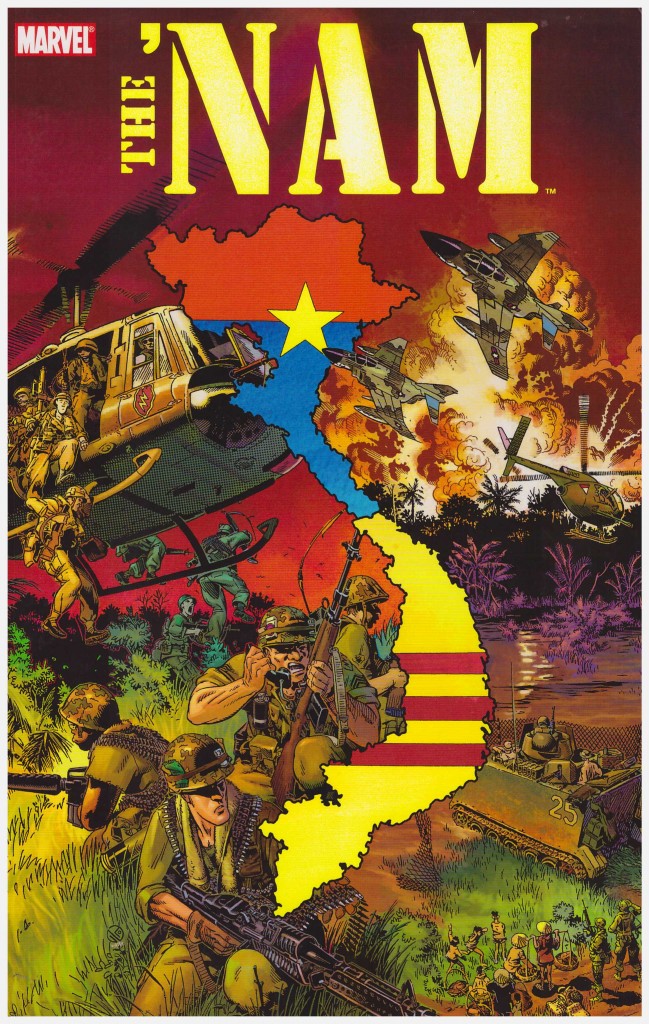

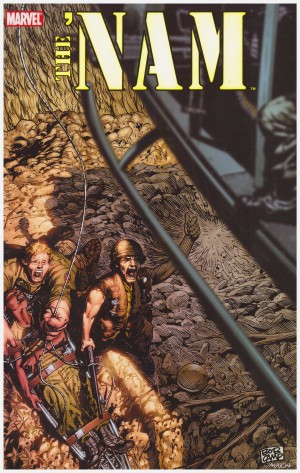

When first published in 1986 The ‘Nam was a massive and surprise hit. Larry Hama notes in his fantastically informative introduction that, although not designed for the purpose, it was a product the publicity department could promote to newspaper editors. Their eyes glazed over when X-Men continuity was explained, but The ‘Nam fell within their reference parameters, and therefore reached a far wider audience than anticipated.

This would have been irrelevant without a top class product that audience could relate to. Handed a brief to create a comic about the Vietnam war, Hama, himself a veteran, began with a viewpoint that content would respect those who fought by remaining as true as possible to the combat experience as it was for those who were there. He also decided that the monthly comic would progress in real time. As a month elapsed for the readers, so it would for the troops depicted, who’d be rotated in and out. Provided they survived.

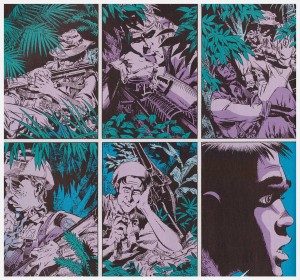

Hama’s chosen writer was Doug Murray, also a veteran who’d written Vietnam stories for a Marvel magazine, co-incidentally drawn by Michael Golden, and reprinted here. Golden is an extraordinarily talented artist who preferred heading off on his bike into the wilderness, but what characterised both the previous stories and this material was his love of hardware. He didn’t draw the troops with generic firearms. Anyone familiar with the Browning M-2 .50 caliber machine gun or the Huey helicopter would recognise them. For all that, his depiction of the Vietnam countryside is lush and alluring, and his cartoon-based style applied to the troops, their posture and facial reactions is extraordinarily expressive.

The narrative focus is Ed Marks, nineteen and a new arrival in Vietnam, reflecting much of the readership, and permitting early dialogue-based information dumps. He hooks up with the 23rd infantry division and progresses from newbie to vet over ten chapters. Murray’s writing style is naturalistic, depicting the perpetual undercurrent of fear, and the tedium, exhaustion and routine punctuated by moments of sheer terror and adrenaline. It’s very effective. He’s also a rare writer happy to leave some storytelling to the art, so greater than usual attention is needed.

There are occasional problems where the desire to convey realism to one segment of the audience results in the novice being bombarded with multiple acronyms and nicknames. Consulting the exhaustive glossary in the rear of the book, isn’t ideal, but Murray also slips a wealth of information into the dialogue, necessary as a lack of expository captions was editorial policy.

Plots cover much routine, a corrupt allocation sergeant, visiting TV journalists, tunnel warfare, accompanying the South Vietnamese in Saigon, a break there, and how a Vietnamese came to be working for the US Army. That chapter was a trial run for artist Wayne Vansant, who would illustrate most of the next two volumes.

In the 1990s Marvel released three graphic novels each collecting four issues of the original title. The colour reproduction was hideous, almost dayglo, and is thankfully corrected for this and the two succeeding volumes.