Review by Ian Keogh

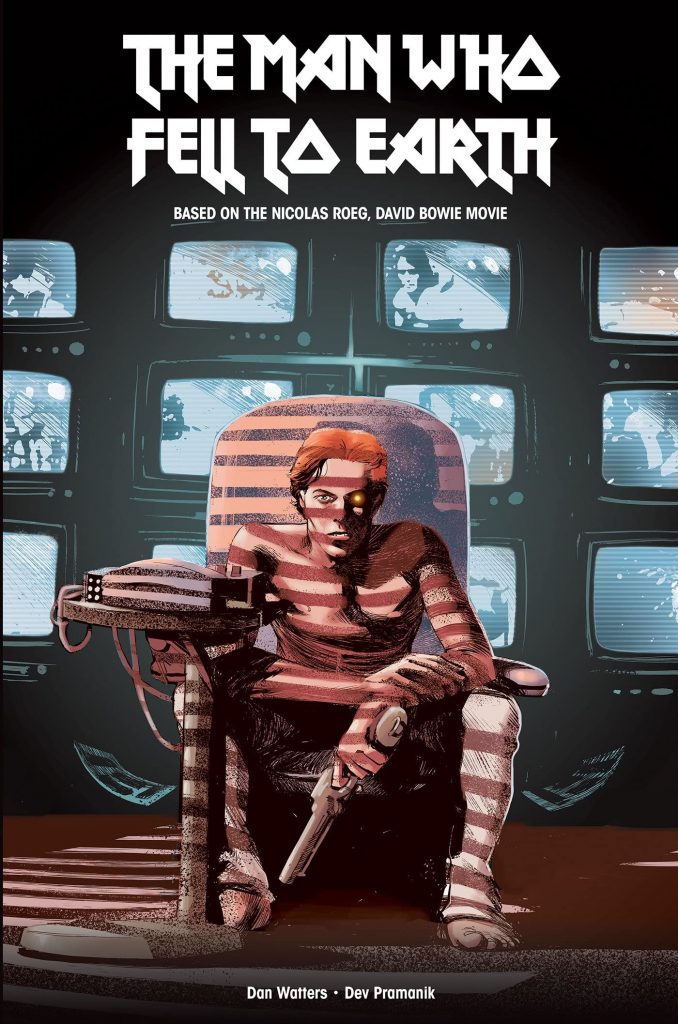

The Man Who Fell to Earth was first conceived by Walter Tevis in his novel of the same name, but is best known for the 1976 movie adaptation by Nicolas Roeg, starring David Bowie. Scripted by Paul Mayersberg, the movie remains polarising, loved by cinema enthusiasts and critics, but not taken to the hearts of the public. The reason Dan Watters and Dev Pramanik’s graphic novel adaptation arrived in 2022 presumably had much to do with the TV series continuing the experiences of alien Thomas Jerome Newton.

Newton arrives in New Mexico, already appearing as human, but masquerading as English as he acquires money by selling gold wedding rings to dealers. The narrative jumps back and forth through time, with Newton’s past commented on by those who’ve met him as if at police interview. They build a picture of someone who needs as much money as possible as rapidly as possible, and sees patenting technology as his best opportunity.

David Bowie’s likeness alone reveals Watters and Pramanik are adapting the movie rather than the novel, but they restore the clarity and relative simplicity of the novel, whereas Roeg, ever the cinematographer, was more concerned with the visual complexity and meditative mood. Newton’s otherness remains, but is conveyed by evasiveness, strange habits and a slightly off-kilter personality. Only Newton’s seeming desire to transport water prevents The Man Who Fell to Earth being a relatively straightforward retelling of Jesus’ life in modern day terms, and just like the story from the gospels, mankind proves disappointing.

Pramanik is a very promising artist, conveying emotional impact in credible locations while keeping likenesses relatively consistent. There’s a slight problem with people being too posed in places, perhaps an inevitable consequence of using the film as extensive visual reference, but this never overwhelms or distracts too much.

Fans of the film ought to enjoy this new interpretation, which is faithful yet speeds up events. As the story itself is relatively short, the book ends with a number of process pages and an essay by Stephen Dalton about the movie.