Review by Ian Keogh

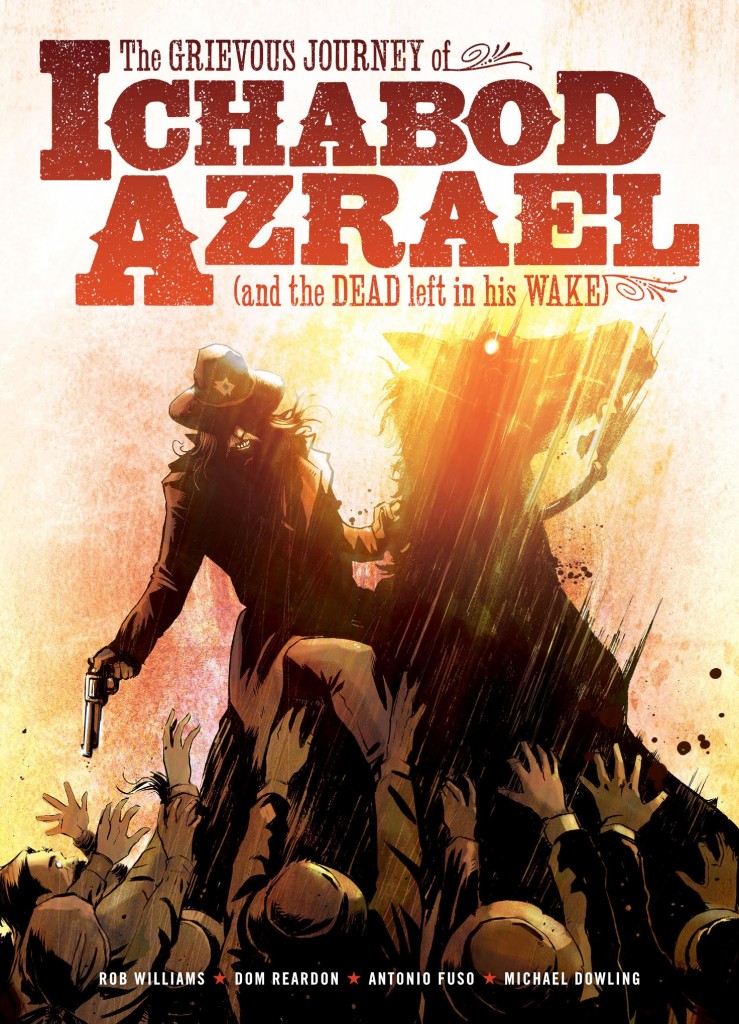

The myth of the immortal killer stalking America’s wild west is a genre well exploited in numerous media, most effectively by Clint Eastwood, an influence strangely absent from Rob Williams’ introductory list. Such is Ichabod Azreal, rotten to the core, yet a deadshot feared by all until his timely demise. Death, however, is not the end for Ichabod who arrives in a new environment his pistols still working, and his mean and spiteful personality unrepentant.

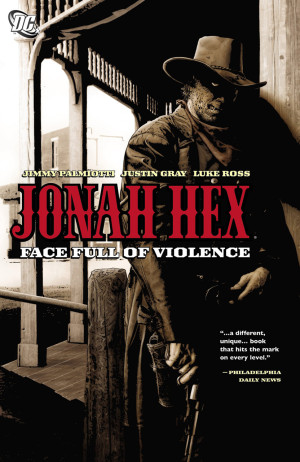

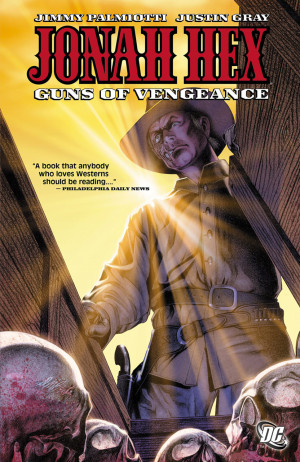

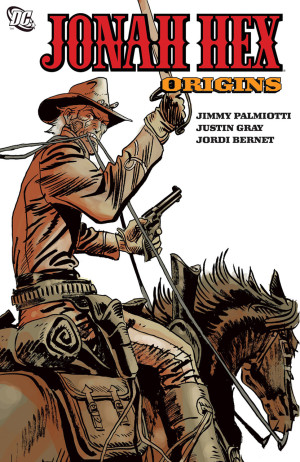

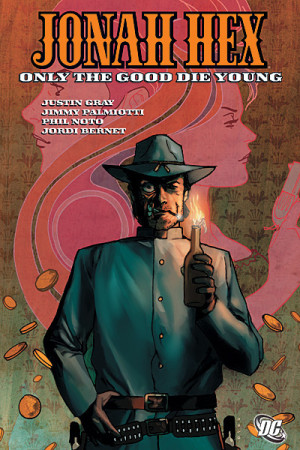

As he also mentions in his introduction, Williams really enjoys himself toying with complexity of archaic sentence formulation, both in the narrative captions and Ichabod’s dialogue. He’s a man of his time given to expressing himself in grandiose fashion, his lexicon almost as much a weapon as his guns, yet in this he’s similar to characters found in Jonah Hex, except not quite as pithy with his comebacks. He’s deposited in a version of hell and determines to find his way back to the land of the living, something only possible via possession of a rogue spirit.

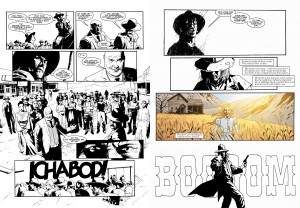

Where Ichabod departs from variations on the familiar is with the anomalies he encounters. Williams is greatly imaginative when it comes to these, raising questions and providing visual spectacle for Dom Reardon to illustrate in his scratchy and jagged fashion. This is distinctively carried out, separating Ichabod’s netherworld experiences from life on 19th century planet Earth via a drift into black and white artwork.

This quest, however, is but the start of Ichabod’s journey, and when it continues Williams removes him from his influences by jumping forward to World War I then a decade further. Distancing those influences, however, diminishes Ichabod as a character. Williams ends his opening story with a clever explanation as to what’s been happening, but despite still providing Reardon and joint artist Antonio Fuso with memorable visual imagery, and introducing a viable new catastrophe, his continuation isn’t as gripping.

‘One Last Bullet’ ends Ichabod’s story, now with Michael Dowling illustrating. In terms of shadowy monochrome his style is similar to that of Reardon, but based more in naturalism, and very impressive. He’s helped by Williams restoring Ichabod to a more natural habitat, and adding some extra visual trickery to his script.

Over the trilogy Ichabod’s tale is ultimately that of redemption via the surmounting of insurmountable odds, Williams’ positing that even the most intransigent of killers can be transformed by necessary circumstance. Not every aspect works, but it’s never less than visually stimulating, with space well used and very much something different for 2000AD.