Review by Frank Plowright

The Fade Out is essentially the story of two men needing different forms of redemption and how it might be provided by the secret they know about an actress who supposedly committed suicide.

The Hollywood setting in 1948 binds everything together. It allows World War II to have been recent, while the end of the studio system is imminent, the FBI have begun their anti-Communist witch hunt, prejudice is rife and the era of kid gang adventure films is within living memory. Ed Brubaker uses them all in his focus on screenwriter Charlie Parish, who has problems even before the first page, having been unable to write since returning from his World War II service. Brubaker is smart in never spelling out the circumstances, as they’re narratively irrelevant and would only distract from the ongoing plot. He’s come to an arrangement with blacklisted and alcoholic writer Gil Mason, who produces the scripts under Charlie’s name, keeping them both employed.

Sparking events is Charlie awakening in a bath, stumbling through to a living room and seeing the corpse of Valeria Sommers, the leading actress in the film he’s working on. He knows he couldn’t have killed her, but his memory is otherwise foggy about the events of the previous night. His sense of self-preservation, though, is still operating, and he vacates the premises. When Valeria’s death becomes public it’s as suicide, complete with police pictures of her hanging. Charlie and Gil are both outraged, but what can they do when the system ensures the studio version is always gospel.

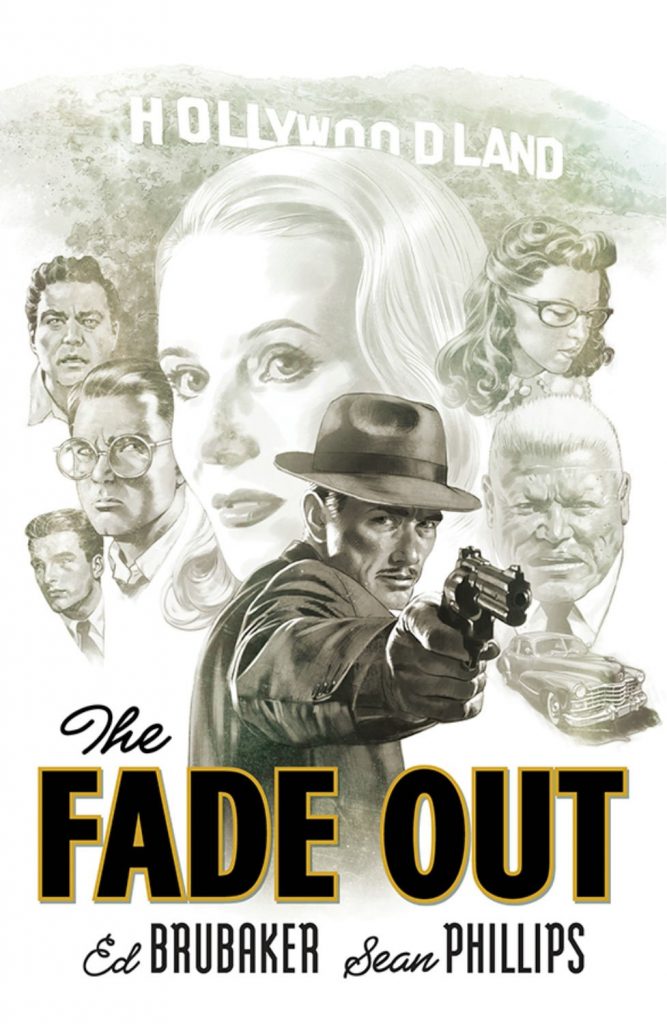

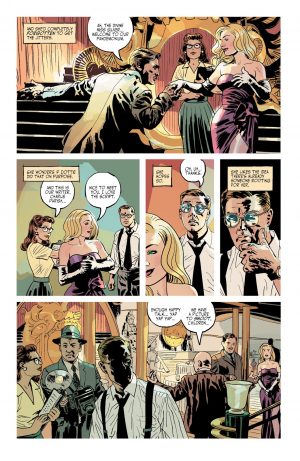

While Brubaker supplies the opportunity, it’s the art of Sean Phillips that nails the seedy atmosphere of uncomfortable people, tarnished glamour and filmed artifice. The story is prefaced by eighteen portraits of the ensemble cast, each given a different expression and a slightly different pose by Phillips, and each of them superb and defining a personality. That’s the work Phillips has put in before the story even begins, and his diligence continues throughout, defining emotions, locations and accessories, the era’s cars standing out.

The Fade Out is styled as a cinematic noir mystery, but the strength is the fully rounded cast, even those with smaller roles having motivations fully understood. An example of those is Dotty, the studio publicist who stages events for the press. Readers realise she’s attracted to Charlie, but he doesn’t. Those who know their cinema history are aware a new dawn is coming, but Charlie lives his past and present and doesn’t see much of a future. Stylishly downbeat, The Fade Out shreds cinematic myth and reveals the grim underbelly with a consistent lack of sentimentality. It’s brilliant.