Review by Frank Plowright

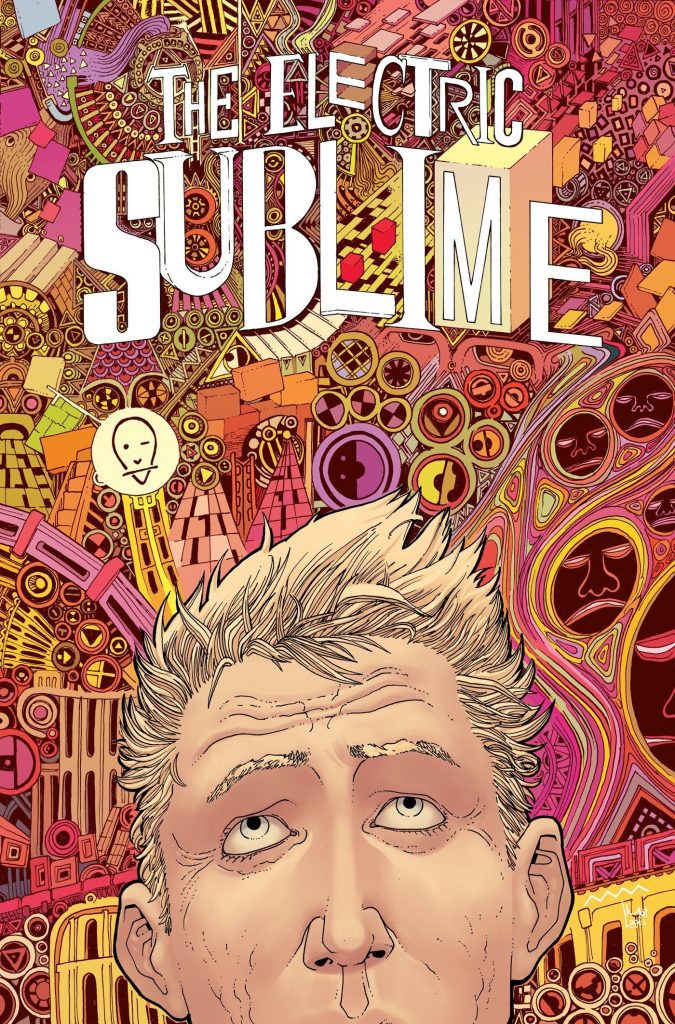

Considering art is so important to the comic form it’s surprising how few graphic novels tackle it head on. Biographies of artists are plentiful, but are frequently concerned more with the details of a life lived than a painting produced, but for The Electric Sublime W. Maxwell Prince and Martín Morazzo concoct a world around art. Unhinged visionaries are confined to sanatoriums, yet when paintings mutate only they can connect with the soul of the painting, and in some cases restore it. Others are lost forever.

Although he’s writing about art, Prince’s meditation are applicable to any creative endeavour when it comes to the creator’s dissatisfaction with their creation. The best artists strive for perfection, while imperfection is something to be rooted out and destroyed. It’s a dangerous line to tread, and yet one that fuels a plot about crimes either affecting art or destroying artists, with art itself developing the power to fight back. When passion and authenticity is all, Matisse’s daft comment that every painter should cut out their tongue is something to be followed through, and that’s when Inspector Breslin of the Bureau for Artistic Integrity becomes involved.

Given the theme, it takes a talented artist to ensure it comes to life. Sure, Morazzo can shop in a copy of Mona Lisa or the background swirls from The Scream, but most of the remainder is down to him, be it figurative or abstract work, and it’s remarkably good. Morazzo has a refined sense of composition, a delicate line and is adaptable enough to set scenes within pastiches of known artwork. He’s also responsible for some engagingly strange looking people. Not all art is about beauty. In order for the plot to have maximum engagement the real world art involved is perhaps too obvious, but using Mona Lisa, for instance, also enables Morazzo’s line perfect reconstruction of the Louvre. When it comes to the surreal, colourist Mat Lopes acquires a greater importance, yet there’s no little irony about the art illustrating a story about art being a collaboration.

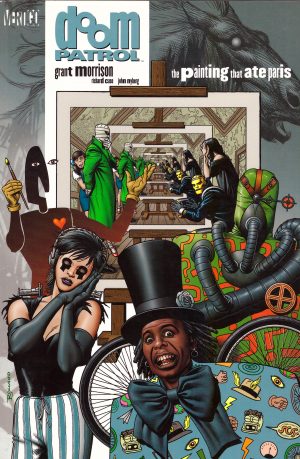

The Electric Sublime owes some debt to a Grant Morrison Doom Patrol story ‘The Painting That Ate Paris’, exploring similar ideas from a dadaist perspective. While it’s violent, silly and interesting, and a demented Andy Warhol is great, it also feels compromised, the action sequences contrived to deliver the meditations on art. That’s a pragmatic commercial decision, but it sets up an uneasy creative conflict. The ambition from a largely unknown creative team is praiseworthy, and by the standards of most action graphic novels The Electric Sublime is a success, but it’s not the full monty.

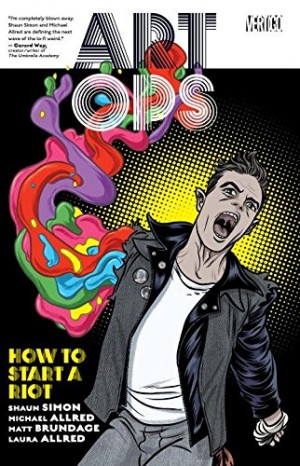

However, Prince seems to have realised that, and when the rights reverted he tinkered slightly, adding background strips, and as Art Brut the hardcover reissue is more satisfying.