Review by Woodrow Phoenix

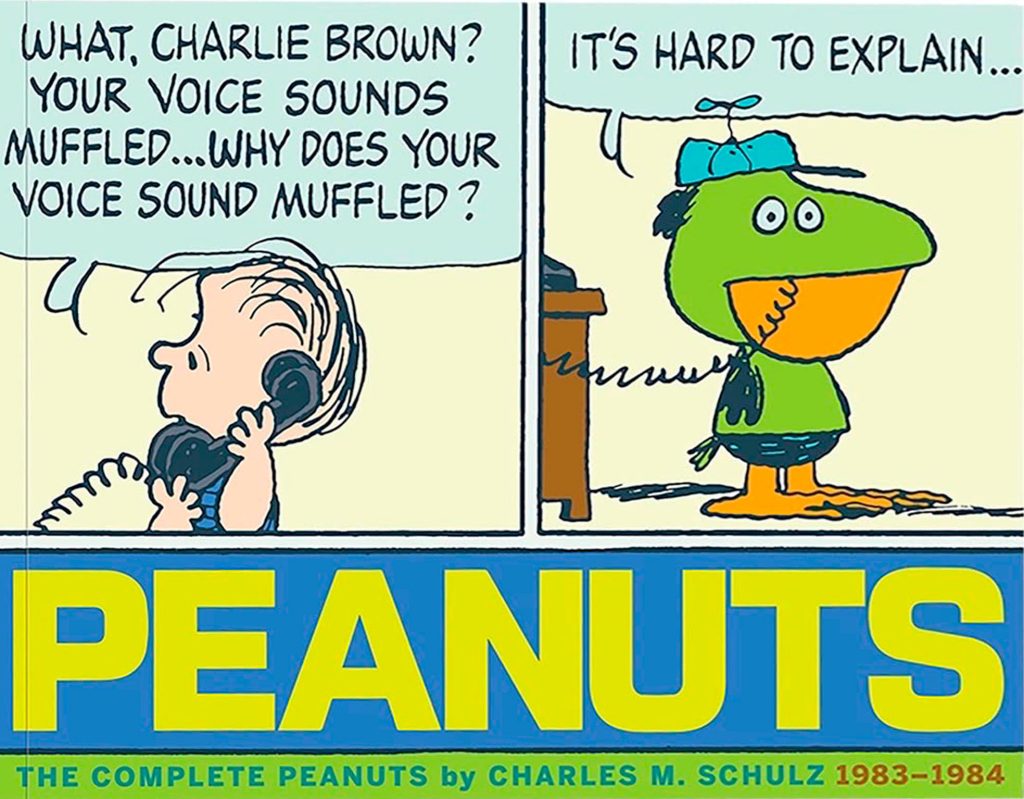

Volume seventeen of this definitive collection of The Complete Peanuts features every single daily and Sunday strip produced by Charles M. Schulz between 1983 and 1984. As Peanuts passes its thirtieth year Schulz is still shaking up his routines and giving his cast different things to think and do that play off what we know about them. Some of those variations prove to be surprisingly funny, as in an extended sequence where Peppermint Patty’s continual D-minuses, constant sleeping at her desk, terrible or incomplete homework and worthless book reports finally result in disaster. Or a variant of disaster that turns out pretty well for her, to Marcie’s exasperation. “Years ago, there used to be a radio program called ‘It pays to be Ignorant’”, she tells Patty. The jokes continue when Patty’s personality turns out to be so powerfully imprinted on her empty seat in front of Marcie that her absence is as annoying to everyone as her presence.

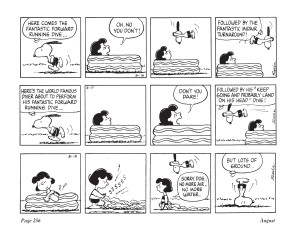

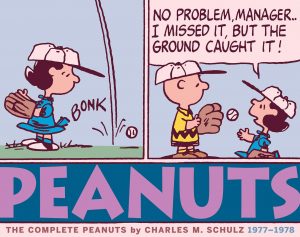

Less successful are the interludes with Snoopy’s droopy brother Spike, out in the desert with his only friend, a large cactus. It’s hard to know whether the repetitive and underwhelming philosophy and the mildly downbeat situations are supposed to be deliberately flat, as an experiment in contrast to Snoopy’s parade of brasher, always popular, always winning personas. It might work in small doses, but the idea can’t sustain extended exposure and interest wears off very quickly. Sally’s insistence on Linus being her ‘Sweet Babboo’ is wearing thin by this point too, although there is a great exchange between Charlie Brown and Lucy in the middle of it all. Charlie Brown also suffers his most humiliating baseball experience yet at the hands of Peppermint Patty, after he excitedly agrees to join her team without thinking through what use she might have for someone who consistently fails to ever win a match. There’s also a promising progression for Linus when he gives up his security blanket and then starts a support group for other kids who are trying to get away from theirs.

The introduction to this volume is by writer Leonard Maltin.