Review by Graham Johnstone

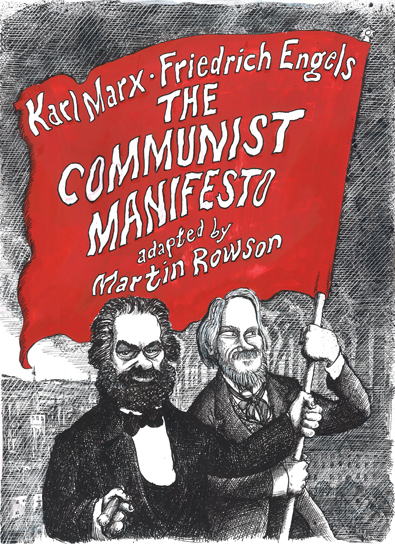

Martin Rowson is famous, in Britain at least, for his acerbic political cartoons. He’s perhaps less well-known for his comics adaptations of classic literature – including pioneering experimental novel Tristram Shandy and modernist poem The Waste Land. His move into non-fiction, with Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto, is both brilliantly inspired and perfectly logical.

Rowson’s previous adaptations have been loose: vehicles for his own improvisation, parody and commentary. In contrast, Rowson’s adaption of The Communist Manifesto is faithful and complete, his commentary on the source, confined to an illustrated introduction. This bulks the contents up to viable book length, yet proves a welcome addition that roots the adaptation in Rowson’s personal experience, providing context on the manifesto’s creation, and considering it from the perspective of the 21st Century. It’s illustrated with panoramic spreads of mankind’s collective struggles, from pre-history to mid 19th Century – the time of the Manifesto’s creation.

The Manifesto itself might seem, even to the politically sympathetic, a dry and difficult text to visualise. In fact, it’s a gift. Marx uses gripping, colourful language, perhaps to connect with the ‘proletariat’ – working people, generally excluded from education. He compares, for example, contemporary means of production with “a sorcerer… who is no longer able to control […] the powers he has called up by his spells!”

Rowson’s background in literature rather than art, has been typically evident in weak composition, lacklustre rendering, passable figures, and caricatures, (the jut-eared, grinning, Tony Blair in Gulliver), surely borrowed from his Guardian colleague, Steve Bell. Instead of investing time in refining these key visual elements, Rowson seemed to have diverted his energy into over-wrought inking that – given his own overuse of faecal imagery – could fairly be called anal. Rowson’s great strength, though, has been his cartoonist’s ability to encapsulate abstract and political ideas in symbolic imagery.

This look at Rowson’s past aims, (in the manner of Marx), is to make sense of the present. Here he plays to his visual strengths while addressing his weaknesses. The pages of traditional line-art comics panels are easier on the eye, and his caricatured likenesses (cover image) more finessed. Where he really takes flight, though, is the panoramic spreads. These take obvious inspiration from the symbolic cartoons of James Gillray but less obviously, the apocalyptic visions of painter John Martin. In the Manifesto’s terms, Rowson’s use of this ‘technology’ maximises his labour power, and adds considerable value. One of the best images depicts Marx’s ‘conjured’ forces now out of control: industry – a steam-powered behemoth – is toppled by ticker-tape machines with demon wings, that spew out reports of the new stock-market capitalism.

We’re guided through this burlesque show of capitalism by Marx and Engels’ cartoon avatars – gas-masked against the pollution, or astride a flying pig. Their speech balloons narrate the entire text. This adds a sense of immediacy, though also some unwieldy balloon chains, resulting in a breathless read, without convenient pause to absorb the visuals.

Published on the bicentenary of Marx’s birth, Rowson’s adaptation is timely in a more profound way – as people around the world increasingly see their political systems failing, and hunger for alternatives. Despite some niggles, Rowson’s bold adaptation deserves to bring these important ideas to a new audience.