Review by Frank Plowright

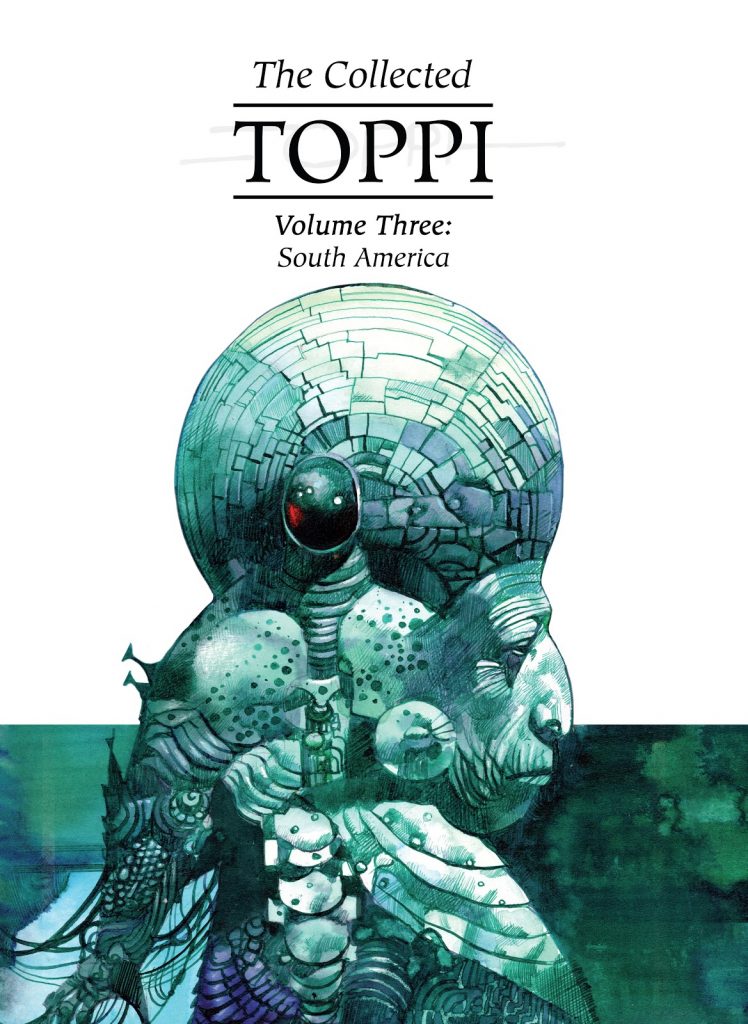

The immediate difference between South America and all other volumes of The Collected Toppi is that half the pages are coloured. A single short colour story featured in North America, but otherwise in the other books internal colour is restricted to reproduction of covers from earlier collections of Toppi’s work. It’s a strange experience, and almost distracts from his virtuosity. That, though, is underlined in Dave McKean’s introduction, which among other erudite and insightful observations notes the importance of abstract design in the creation of Toppi’s imagery, which is something the colour brings through. There are numerous examples throughout this collection of the fantastic way Toppi constructs rocks, but the look of them on the colour art toys with the eye, deceiving it into visual misrepresentation and abstraction. That effect is further apparent on the outstanding cover portrait.

Although having the shortest timespan encompassing the creation of these stories (1976 to 1992), the past remains Toppi’s canvas, opening with a curious tale set during the Spanish invasion of Central America. Horrific by our standards, and fatalistic, it certainly sets the tone of what follows. The volume title, by the way, strangely refers to anything south of the USA.

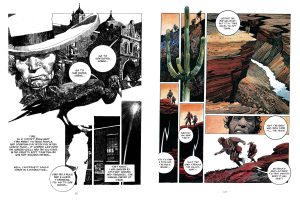

‘Chapungo’ is titled after the lead character, and Toppi echoes The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in showing how a lust for something can transform a person, and acknowledges the inspiration via naming a mining company after it. He also echoes the past via emphasising that winning a battle isn’t the same as winning a war. We first hear from American pilots of a plane that’s rumoured to have crashed in a remote and dangerous area carrying a lot of gold. Chapungo learns the story also, and is determined to find the treasure. The ending is slightly sting in the tail, weaker than it might have been, but Chapungo’s single-mindedness is frightening.

Over 46 pages ‘The Legend of Potosi’ meanders, Toppi returning in 1992 to the theme of a man motivated by riches, but with a more abstract desire. It’s magnificently drawn, although slightly simpler to accommodate the colour, which varies considerably from page to page. There are some magnificent scenes of Inca culture, of wildlife and beautifully drawn people, but it’s also episodic, and doesn’t hang together as well as Toppi’s shorter material, switching location according to what Toppi wants to draw. It’s enigmatic. Do the half dozen incidents seen of Potosi’s life add up to a wasted existence, or has he been given direction he would otherwise lack, and experienced so much more? His legend is revealed at the end, cleverly anonymous to conclude a story in which Potosi is only once called by his name.

All bar the opening story are considerations of desire as a driving force, and ‘The Treasure of Cibola’ is the most complete. A masterpiece, in fact. The colour is more strikingly applied, and there’s a far greater strength to the story of a middle-aged soldier given one last chance of realising his dreams. Toppi accentuates the vastness of nature, provides some startling images and he sets a melancholy mood from the opening pages, establishing that Cuchillo’s life has been one of expectations unfulfilled. Is this to be his redemption or a final failure? Emotionally rich, surprising and tragic, in a lifetime of noteworthy work, this stands among the contenders for Toppi’s best story, so while some of the earlier content doesn’t always hit the bullseye, these 46 pages make South America an essential purchase.

Next is The Cradle of Life, considering the areas of Earth’s oldest cultures.