Review by Frank Plowright

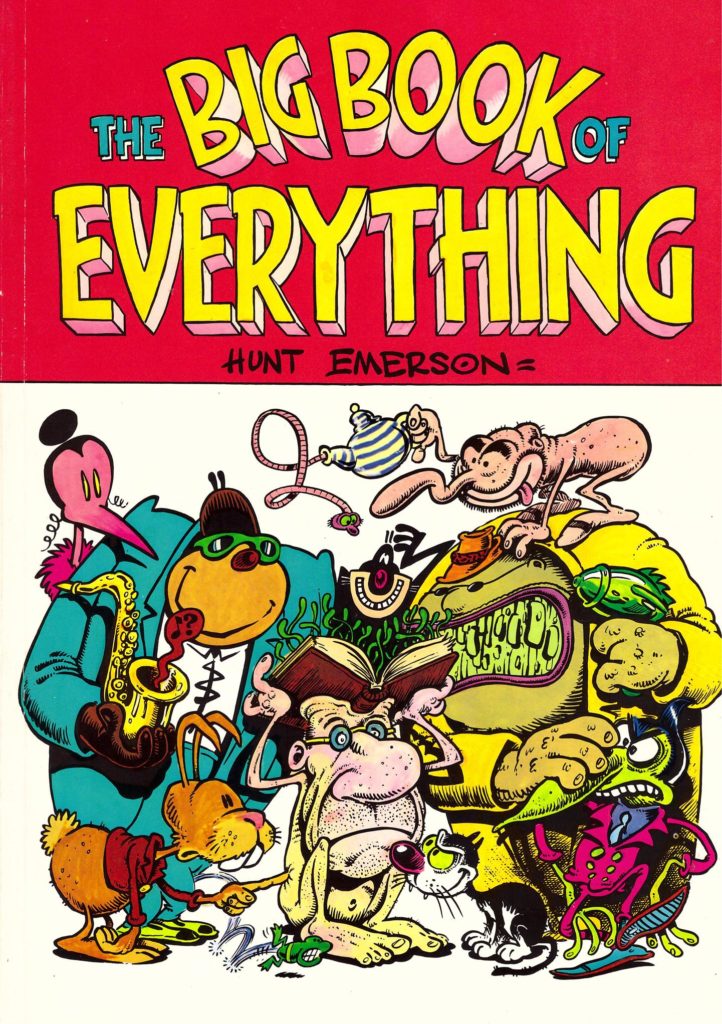

By 1983 Hunt Emerson was already head and shoulders above his fellow British underground cartoonists, actually a fairly select group, most of them published by Knockabout. A retrospective was a more than viable creative and commercial proposition, and The Big Book of Everything was the result. Just as the running order was a matter of considerable debate for bands in the pre-digital era, so a choice is made here. A vague thematic succession is prioritised above chronological sequencing, but strangely coincidental pointers to later work appear.

Around a decade of contributions to anthologies both British and American are gathered, and what they show collectively is that while Emerson was a wildly inventive artist from the start, his writing took far longer to develop. The cartooning carries slim, often surreal stories a long way, and Emerson’s influences are there to see, almost all anarchic. Given the publications he contributed to, it’s only to be expected that American underground artists are a big influence, particularly Gilbert Shelton. However, being British, and growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, Emerson couldn’t have failed to be influenced by Leo Baxendale, and the Warner Brothers cartoons regularly screened on British television. His earliest work takes a lot from George Herriman’s Krazy Kat also. This shouldn’t suggest Emerson’s only skill is pastiche, he quickly develops his own style, or styles, actually. Stories of perpetual sad sack sax player Max Zillion are densely packed, vibrantly kinetic and doused in ink, while others are leading figures set against constantly shifting backgrounds, that Herriman influence shining through. It’s now strange to see Emerson attempting a more realistic style for the likes of 1950s sci-fi pastiche ‘Stir Crazy’

As noted, the writing lags behind, Emerson already knee deep in slapstick, but his comedy timing not fully developed. Pretty well all the humour is in the funny drawings, with the Max Zillion strips having a pathos lifting them above the frenetic nature of much else. Calculus Cat transmits as the most personal work, a character forced to conform to expectation outside his house and constantly tormented within.

Although possibly not designed as such, The Big Book of Everything draws a line. Alan Rabbit, also known as Bill the Bunny, would disappear while Emerson concentrated on Max Zillion, Calculus Cat and adapting literary giants, providing the slapstick they’d inconsiderately excised from their works. Collaborations also followed, crucially with Tym Manley for men’s magazine Fiesta actually providing an income, and those collaborations with others are gathered in the 1990 collection, Rapid Reflexes.

This is a timepiece, the earlier cartooning rough and unfocussed, but already with the spark of comic genius, the later strips amazingly well drawn, of considerable value irrespective of the scripts. It’s astounding now to see the original cover price of £3.95. It was worth more then, and certainly much more now.