Review by Ian Keogh

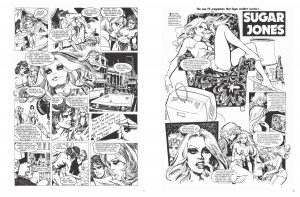

The typeset paragraph introducing each Sugar Jones episode just oozes Pat Mills’ personality, describing a much loved and glamorous TV star in truth completely selfish, over forty and made-up to pass for a woman half her age. It’s probably not what was expected for the generally safe and compliant girls’ stories of the 1970s. Mills then proceeds to put the hateful woman through a succession of cleverly plotted embarrassments as all her deceit comes to nothing, with her long-suffering assistant Susie providing the reactions of readers. It’s easy to imagine Mills chuckling away over his typewriter as he wrote the scripts.

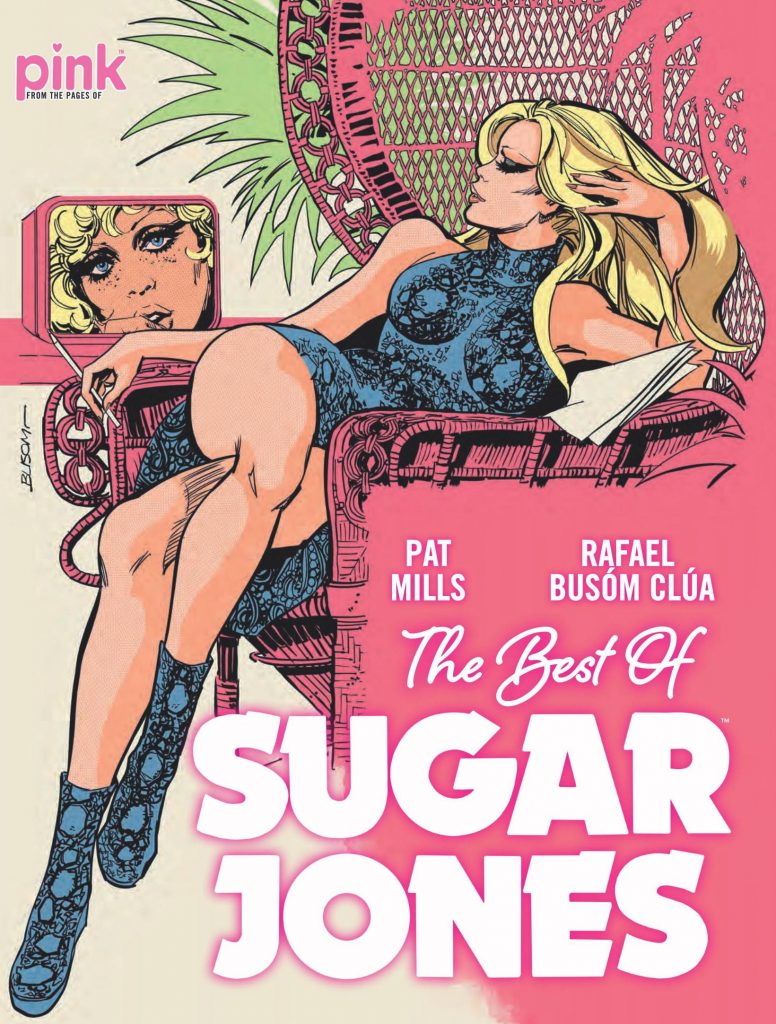

As funny as the stories still are, they’re elevated by the stunning art of Rafael Busóm Clúa. Spanish artists working for IPC through an agency in the 1970s used a similar style characterised by ambitious layouts allowing for an eye-catching larger lead-in panel and great attention paid to hair, fashions and make-up. Clúa’s variation includes what were for the time and intended age group quite sexually provocative poses, draping Sugar seductively in chairs and across beds. Many a young lad surely sneaked a look at their sister’s Pink comic where Sugar Jones originally appeared. Artistically, part of the joke is that the long-suffering Susie, frequently insulted by Sugar, is every bit as attractively drawn.

Older readers will recognise the thinly disguised celebrities, TV shows and social situations Mills feeds into the stories, but not knowing who they are will hardly spoil the enjoyment of a few episodes at a time. That’s the best way to work through The Best of Sugar Jones, admiring the art as you go. Because he was only allocated three pages an episode, Mills resorts to formula. Each episode begins with Sugar’s latest campaign, desire or scheme, and three pages later, largely through her own manipulative poor judgement and selfishness, she’s deservedly come a cropper. The primary variation is Susie managing to undermine or derail Sugar’s conniving, but Sugar remains vain and manipulative. It’s a clever formula in subverting whatever wholesome editorial strictures were in place at the time, as while every episode underlines that cheats don’t prosper, Mills knows the audience delight is in Sugar’s appalling behaviour. The original weekly publication prevented the repetition being so obvious.

The glimpse behind the curtain at Sugar’s unprincipled greed for fame and money was very much ahead of its time, with some current TV stars not even bothering to disguise their similar personalities. The final episode is even set on a baking show. Taking a random story, Sugar is impressed with American TV cop show Lady Law, and decides there ought to be a British version starring her. Fortunately the producer is in London, staying in a hotel surrounded by banks. Uncannily, they’re all being robbed within sight of the producer’s hotel window, and Sugar is on hand to stop the crooks before they make their escape. As this escapade occurs halfway through the collection readers will be wise to the likelihood of Sugar having arranged the robberies, and for once Susie can’t foil the plan by contacting the producer to tell him the truth. A triumphant Sugar announces she’s been booked as the star of a new TV drama. The way Mills subverts the triumph in the final panel is contrived, but well set-up and nicely paced, and the same level of attention applies to every other strip.