Review by Ian Keogh

The more time that passes, the greater the Beat writers become swamped in what preceded and followed their mid 1950s to early 1960s peak. However, as Paul Buhle and Harvey Pekar’s introduction notes, they introduced lasting new ideas about art and culture, while resetting the boundaries of what was acceptable.

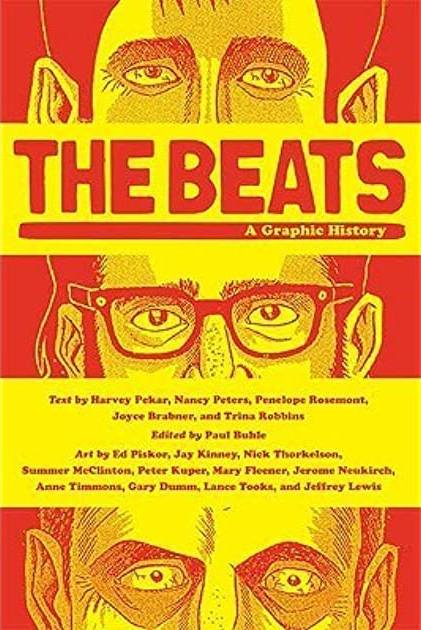

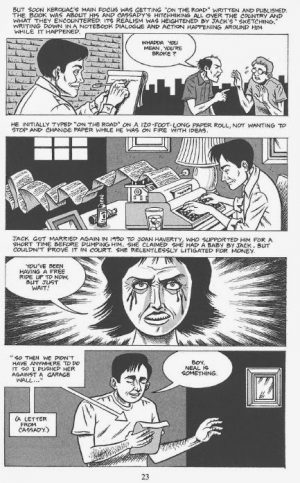

While others contribute, Pekar writes most of the book, while Ed Piskor draws over half of it starting with biographies of Beat’s holy trilogy: Jack Kerouac, Allan Ginsberg and William Burroughs. Although their lives are intimately entwined, Pekar writes a separate biography for each, although two are briefer following their lives after Kerouac’s death. None of the three can be accused of not walking it as they wrote it, hand to mouth and dissolute being a way of life. It may or may not have been Pekar’s intention, but there’s a car crash fascination about all three lives, yet Pekar brings out how those experiences were inextricably linked with their writing, occasionally introducing his own assessment of that. Ginsberg is the most naturally curious about expanding his horizons, much of his travel through choice instead of necessity, and the most adaptable in acclimatising to changing times from the mid-1960s.

Piskor’s illustrations capture the sheer madness of much that’s related, while providing consistent portraits of the leading figures beyond the most famous trio. He’s very influenced by Daniel Clowes, especially when it comes to the thousand yard stares, represented on the cover. Other contributors have different approaches, with Peter Kuper’s presentation of Gary Snyder’s life within the branches of a tree being especially memorable. Also notable is Mary Fleener’s presentation of Diane diPrima’s achievements. She’s one of many beat writers whose interest turned to spiritualism.

In addition to spotlighting other important figures from Beat culture, with an appreciation of Kenneth Patchen standing out, Pekar begins to mix more of each creator’s work into these briefer biographies of other important figures, and also looks back to their influences.

Still more leading lights are highlighted when other creators become involved. Editor Paul Buhle in the company of Nancy J. Peters, and Jay Kinney explain the lasting importance of San Francisco’s City Lights bookstore, and despite Piskor having drawn so much of the book, the appearance of other artists isn’t intrusive. They build on his thorough depictions.

Joyce Brabner isn’t such a clear writer, but there’s a fire to her highlighting the Beat hierarchy’s shabby attitudes to women. Summer McClinton draws the lives shattered and the creativity suppressed in the name of swaggering braggadocio. Closing The Beats we learn about painters Jay Defeo and Jackson Pollock, and poet Tulli Kupferberg who formed rock band The Fugs, and the more tragic d.a. Levy. They all led interesting lives.

If you’re open-minded, being in the company of any enthusiast can be a treat, no matter their sphere of interest, and Pekar is an inspired guide, his textured commentaries bringing personalities and their achievements to life.