Review by Frank Plowright

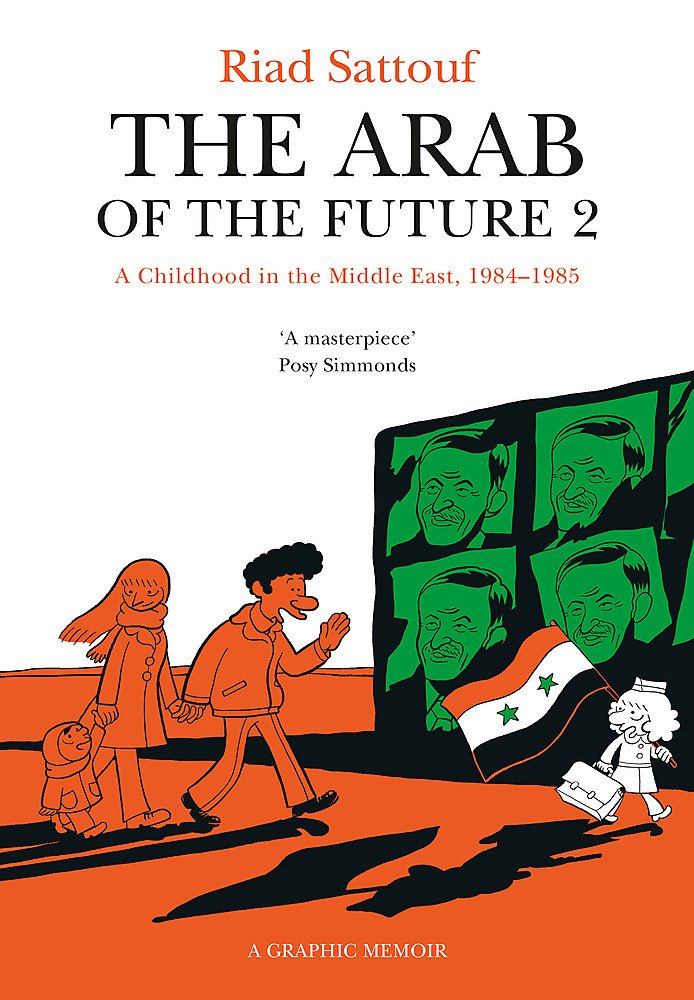

The opening volume of Riad Sattouf’s childhood memoirs related how his family moved between France, Libya and his father’s homeland of Syria during the first six years of his life. This picks up with the family settled in Syria and even his mother’s entreaties are unable to prevent his attendance at school.

Given Sattouf’s prodigious memory, the detail about the first year of his Syrian education is vast, and anyone who went to a British religious school before the 1980s will squirm uncomfortably as the sadism of Riad’s teacher prompts unwelcome memories. What British children didn’t experience was the additional overt bigotry. In keeping with state policy, Jews are considered the enemy, and Sattouf’s long blonde hair marks him out for attention and the constant need to deny he’s Jewish.

A great strength of the opening volume was its cataloguing of Abdul-Razak Sattouf’s eccentricities. Sattouf’s father was an educated man who claimed to have abandoned religion, yet reverted to old ways, view and superstitions when back in his homeland. Coupled with an astonishing capacity for denying reality, The Arab of the Future 1 presented some jaw-dropping sequences. Here he’s portrayed as altogether more understanding and pragmatic, at times even sensible, although still capable of mindless bluster. While easily blinded by anyone with money or stature, there’s only the occasional lapse, such as considering that female soldiers forced to eat live snakes in front of Syria’s dictator to be an admirable lack of fear. Sattouf also makes more of his mother’s frustrations, as she’s more likely to make her feelings known. She’s still a weaker character, however, for being one-dimensional. There’s never any sense that she actually loves her husband, and is constantly frustrated by him.

There’s a precision to Sattouf’s cartooning and a wonderful sense of character. He’s gifted at capturing a personality with very few lines, whether it be an assortment of unfortunate children or the smug arrogance of generals. As previously, he uses a single colour to identify location, red for Syria and blue for scenes occurring in France for an effective separation.

While the location will be exotic for most English language readers, in general Sattouf’s school experience will have a familiarity, if not in the details, then the general atmosphere, and as they occupy the first third of the book there isn’t such a great sense of visiting another world. That’s provided by the contrast between life in the family village outside Homs and its deprivation, and a visit back to France and the enormous Euromarché superstore. The book’s strongest moment comes when honour killing raises its head. Although not sensationalised, it’s an upsetting sequence, foreshadowed earlier in the book, and cleverly related in ambiguous fashion. We’re left uncertain whether Riad’s father has compromised his feelings in favour of an easy life. It’s the point at which the time Sattouf’s spent explaining his father’s inconsistencies really hits home, enabling the doubt, and all his father’s earlier talk about what the Arab of the future must be is extremely hollow.

By any other standards this is an immensely readable personal recollection, but it drops marginally behind the opening volume because there are fewer absolutely shocking moments.