Review by Ian Keogh

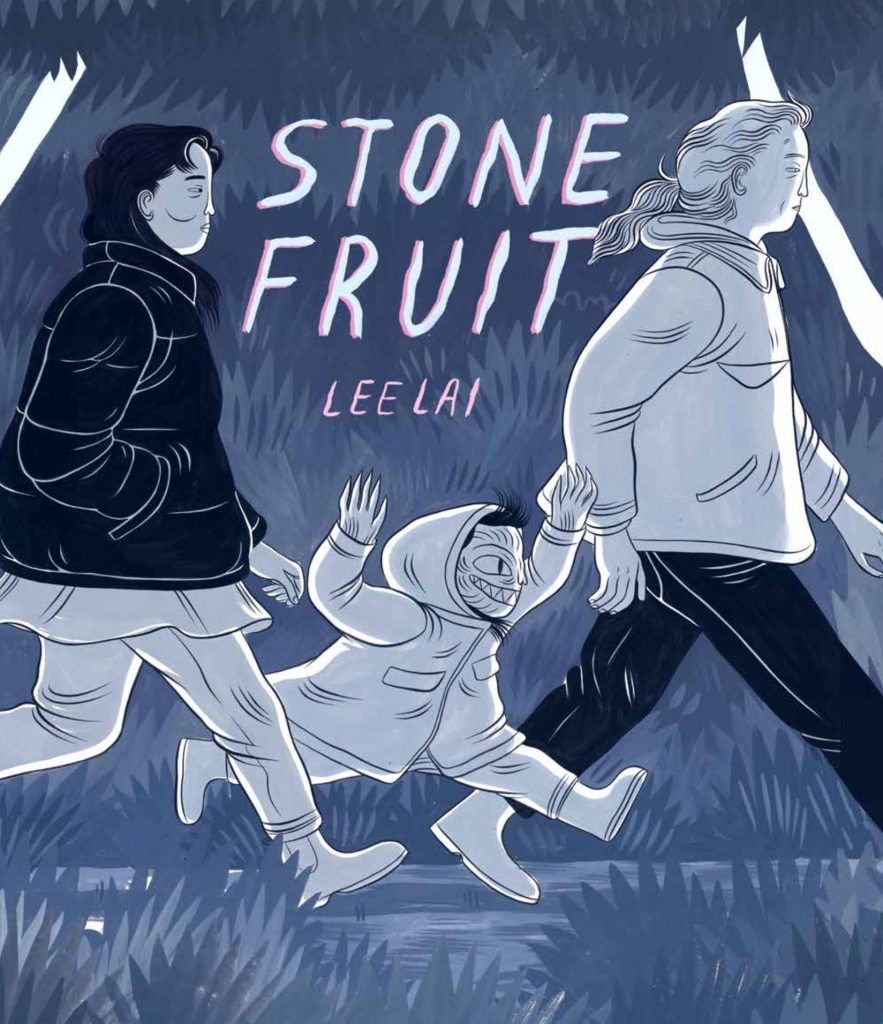

Stone Fruit is an unflinching consideration of the complex and awkward relationships between three women. Rachel lives with Bron, something Rachel’s sister Amanda isn’t comfortable with. It’s not only difficulty with the same sex relationship, but with Bron having depression. The fourth element is Amanda’s daughter Nessie who loves spending time with Aunties Bron and Rachel, although she ultimately fades into the background, her part as possible youthful reflection of the remaining cast played out.

Lee Lai takes a very naturalistic approach to the relationships between very different people, the conversations angry and plausible, and Nessie’s responses having exactly the right tone. Narrative captions and thought balloons are off limits, so dialogue, expressions and posture transmit emotion, although Bron in particular is poor at communicating with Rachel, and that lies at the heart of Stone Fruit. Elsewhere she’s able to be honest and forthright.

There’s also a naturalism about Lai’s carefully considered illustrations, which largely consist of people going about everyday business, but which opens with the liberating twist of Bron, Nessie and Amanda portrayed as feral, reptilian creatures as they romp through the park having fun.

Stone Fruit can be likened to a strong story arc from a British weekly drama, with the people and their feelings strongly transmitted, but the connections never quite being made, while the distance of observation can be frustrating. It’s because fundamentally decent people can’t drop their hurt-related defences, and we want them to connect. While some of her cast have judgemental moments, there’s never a feeling that they’re voicing Lai’s views, as she’s remarkably understanding about topics that for others would be a red line. It’s dealing with the world as it is, rather than as people might want it to be.

The relationships are subtle, and Lai doesn’t always draw attention to the connections. For instance, toward the end it’s revealed that one character’s method of coping with their own life being crap was to pretend to be someone else and modify their responses to the way they imagined that person would be. Does the method also apply elsewhere?

Life doesn’t always supply happy endings, at least in the short term, but fiction often does, so there’ll be a desire that Stone Fruit concludes with a happy resolution. Realising that indicates what a formidable job Lai has done in involving readers in the lives of her cast. There is a resolution, and it’s true to both cast and the problems they’ve been struggling with. It registers Stone Fruit as a remarkably accomplished first graphic novel offering sensitive insight and powerful observation.