Review by Frank Plowright

Lars and Rachel have lived together for a long time, and although Laura is Lars’ daughter from a previous marriage, she cares for her stepmother as she does for her father. As they reach their eighties, however, decline has set in. Formerly simple tasks are now arduous, and although Laura helps as much as she can, help is made more difficult by them not telling her about things that have happened, or diminishing their problems. These are health problems as well as minor irritations.

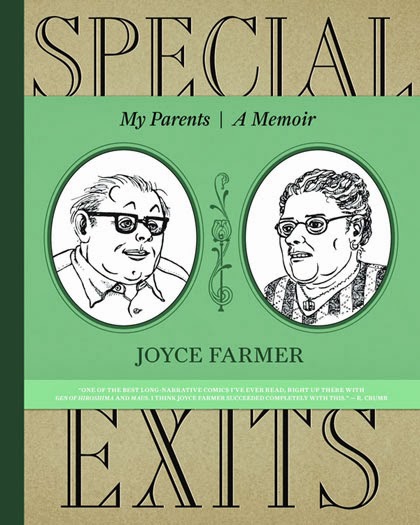

Although she distances herself via the personality of Laura, Joyce Farmer’s memoir concerns her experiences of caring for her parents over a number of years. It’s tragic and heartbreaking, and we know from the start there will be no happy ending. There must have been frustrations and anger that Farmer chooses not to mention, mild exasperation being Laura’s default pit, but the carefully considered art shows the strain on her face. She can maintain a false cheeriness when in Lars and Rachel’s house, but away from it, the pressures show. However, this is no one-sided misery memoir as something brought out exceptionally well is an understanding of Lars and Rachel’s views, and how they cope with an awareness of decline. Farmer avoids the trap of over-sentimentalising, partly by featuring events and anecdotes from Lars and Rachel’s younger days, rounding them as people, not helpless, but sometimes fractious and unreasonable as well as joyful. Other insights are offered by seeing the 1992 Rodney King riots from their viewpoint and how it affects them.

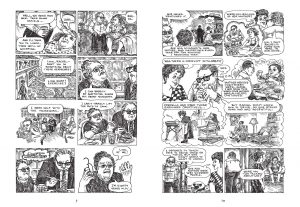

Special Exits took thirteen years to complete, and part of that would be Farmer hoarding details in every panel the way Lars and Rachel keep hold of items just in case they’re useful. It supplies a visual density to accompany the wealth of information supplied over eight tidily drawn panels on every page. Farmer’s very good at visually expressing emotion, and toward the end the restraint in noting the anger and frustration Laura experiences is masterful.

85 pages in, Lars notes that decline occurs in small increments, enabling him to become used to anything. It’s in reference to Rachel’s condition, but it’s a key point, registering how much change has occurred since the beginning. Early on Farmer jumps forward several months at a time, but the need for Laura’s visits escalates, and we see the truth of Lars’ statement as previous necessities slip away. To begin with matters such as a crashed car are concealed through embarrassment, but the lapses become more frequent and memory-related rather than deliberate. Anyone who’s looked after older folk for any period of time will be familiar with the pattern. They’ll also recognise how well Farmer transmits the conflict of guilt and necessity accompanying the realisation that home care will no longer be enough, and the callously dehumanising attitude of some doctors and care administrators. It’s stunning that Laura has to tape a note to her mother’s bed noting she’s blind and has to be fed. Even toward the end, with the inevitable occurring, Lars and Rachel still have surprises to deliver, in one case a stunning, jaw-dropping surprise causing a re-evaluation of an entire life.

Perhaps there could have been a greater exploration of Laura’s feelings, but Farmer has deliberately withheld that. Nevertheless, the personal experiences feeding into Special Exits make it an exceptionally moving memoir.