Review by Graham Johnstone

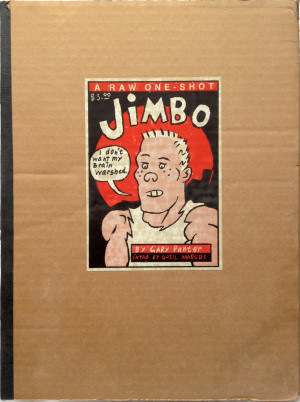

Gary Panter was a pioneering ‘punk’ cartoonist. Inspired by Los Angeles’ 1970s music scene, he created punk everyman Jimbo. So how did he end up adapting John Milton’s 17th Century religious poem?

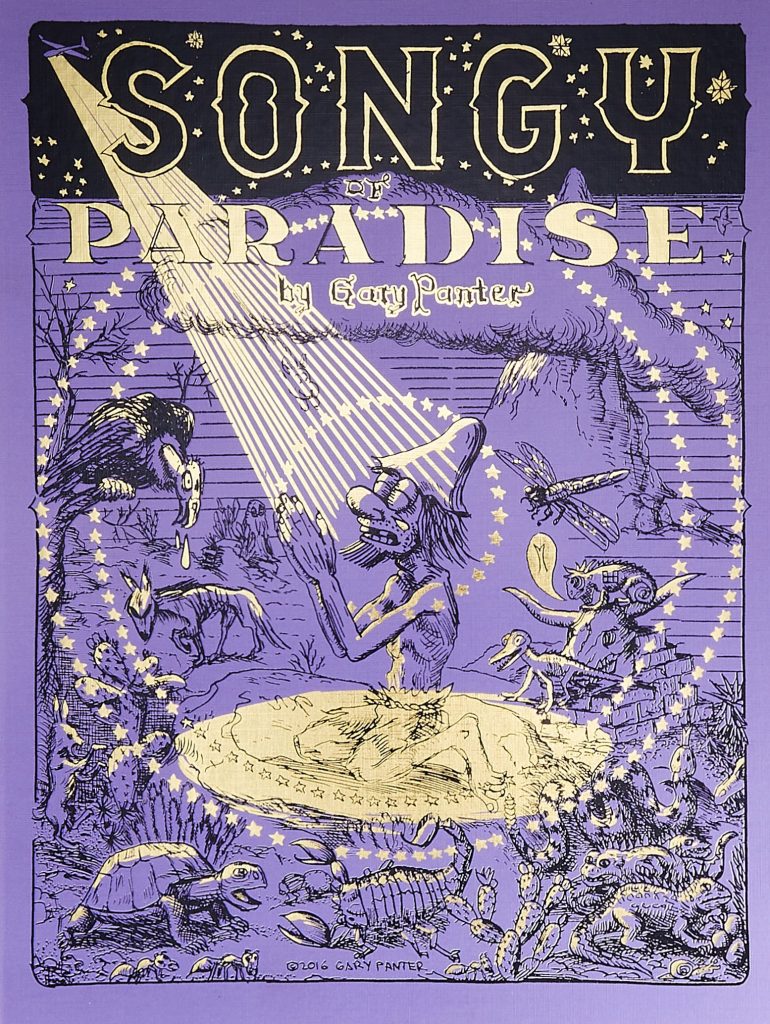

It was a simpler journey than it might seem. Panter’s early Jimbo comics were republished with retrofitted subtitle Adventures in Paradise. This nod to Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy was followed by the properly Dantesque Jimbo in Purgatory, and Jimbo’s Inferno. Despite over four centuries between Dante and Milton, and over forty years for Panter, it’s a logical step from one religious epic poem to another. Songy of Paradise has been described as completing Panter’s religious trilogy, signalled by sharing with Purgatory, and Inferno an oversized hardback format with gold highlights.

Milton remains most famous for Paradise Lost, an epic poem spanning war in heaven, creation of the world, and the fall of man. Its late companion Paradise Regained, in contrast, is classed as a ‘brief epic’, with a narrower focus on the temptation of Christ. The latter poem perhaps offered Panter a different challenge after the celestial scope of Dante.

Building on the credentials of previous adaptations, Panter benefited from a scholarship year amongst the New York Public Library’s rare volumes. The resulting Songy of Paradise retains Milton’s scenario, but updates the details, swapping Judean for American deserts, and Jesus for Songy – a ‘hillbilly’, reflecting Panter’s own rural roots. Otherwise, Songy is true to Milton: adapting each of his four ‘books’ and staging Satan’s temptation strategies (power, status, lust, possessions…) almost blow-by-blow. Panter seizes the challenge of a ‘brief’ epic, culling Milton’s verbosity, and condensing each of the original 32 cantos into a single oversized page. A fine balance between period phrasings and modern vernacular, strengthens an already impressive adaptation.

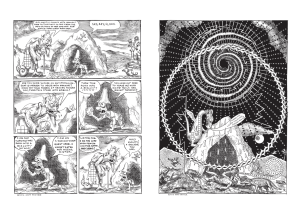

Panter’s earliest pages seized readers’ eyeballs with his feverish energy, artful raggedness, and sheer love of marks on paper. His youthful imagination, and pop culture mash-ups created pages as exciting as anything in comics, perhaps anywhere. Forty years on, Panter’s art is untamed, yet here adapted to his subject: channeling period engravings. He sacrifices his luxurious ink-lines, for marks that might be scored into metal. That’s conceptually correct for both Milton’s era, and hillbilly Songy’s asceticism, but the result is an often arid experience for the reader. The drawn lines, despite their ‘punk’ roughness, lack the compensating charm of Panter’s best. Some sweet swirls of clouds (pictured, left), are offset by too much dreary cross-hatching. Tones are too often a middling-grey against the paper white, with little of the velvety darkness of the earlier books. When spot blacks appear, as, say, ravens crossing the sky, it’s a sip of water under the desert sun.

The Divine Comedy’s immersive cosmology, and inventories of sin, offers inspiring imagery, further enriched with modern/futuristic paraphernalia and pop-culture samplings. However, Songy’s duelling monologues in the desert, (and Panter’s truth to that), offer less inspiration. The Serpent’s ever-mutating form offers some visual interest, but the main attraction is his inventories of temptation. Some of Panter’s modernisations (‘lust-inducing’ fishnet tights and porn poses), seem tired tropes. However, the offered dominion over the Roman Empire, shown bird’s-eye view, with phalanxes, chariots, hand-to-hand combat and resulting carnage, is a visual highlight. Panter’s stoic hillbilly summarily rejects every temptation, so leaving no moments of doubt or desire to dramatise. However, the serpent’s final gambit of possessing Songy’s dreams (pictured, right) provides, the reader, if not Songy, with a glorious release and satisfying climax.

Songy of Paradise is an impressive modernisation of Milton’s vision, though a sometimes demanding read.