Review by Jamie McNeil

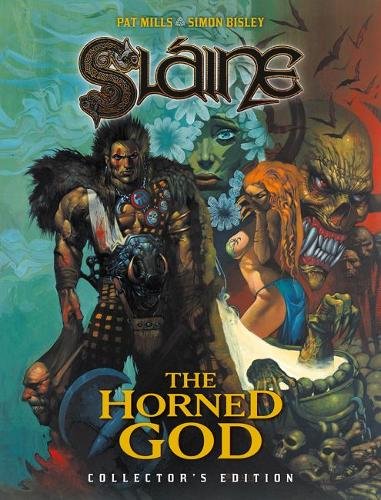

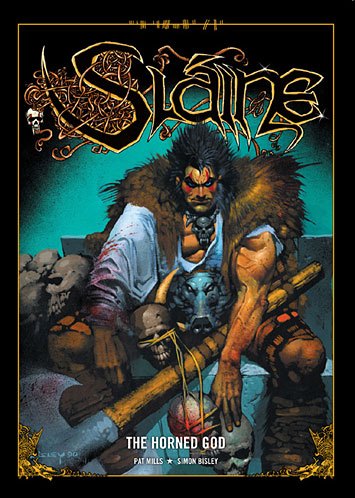

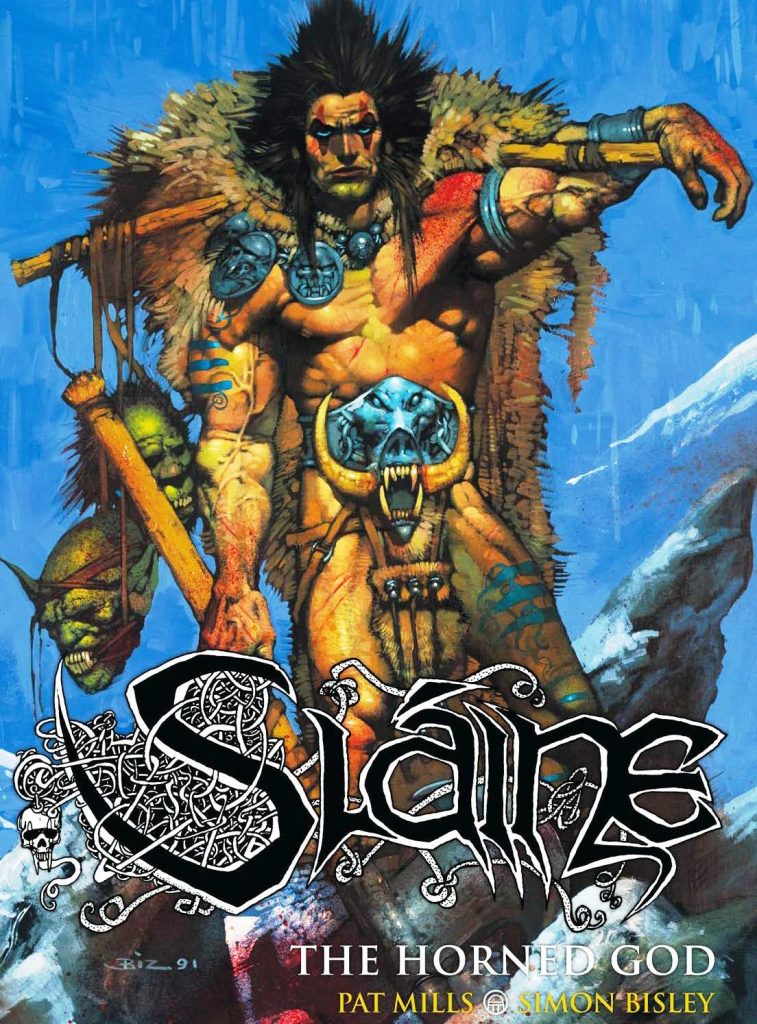

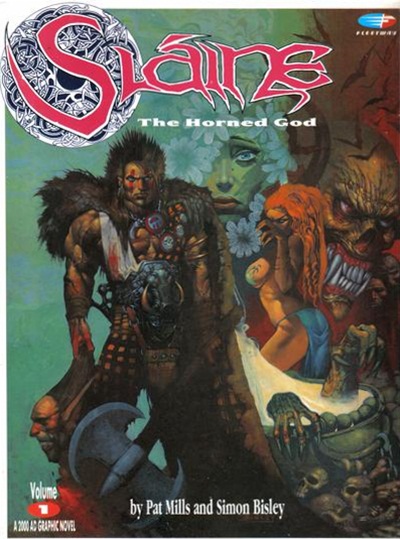

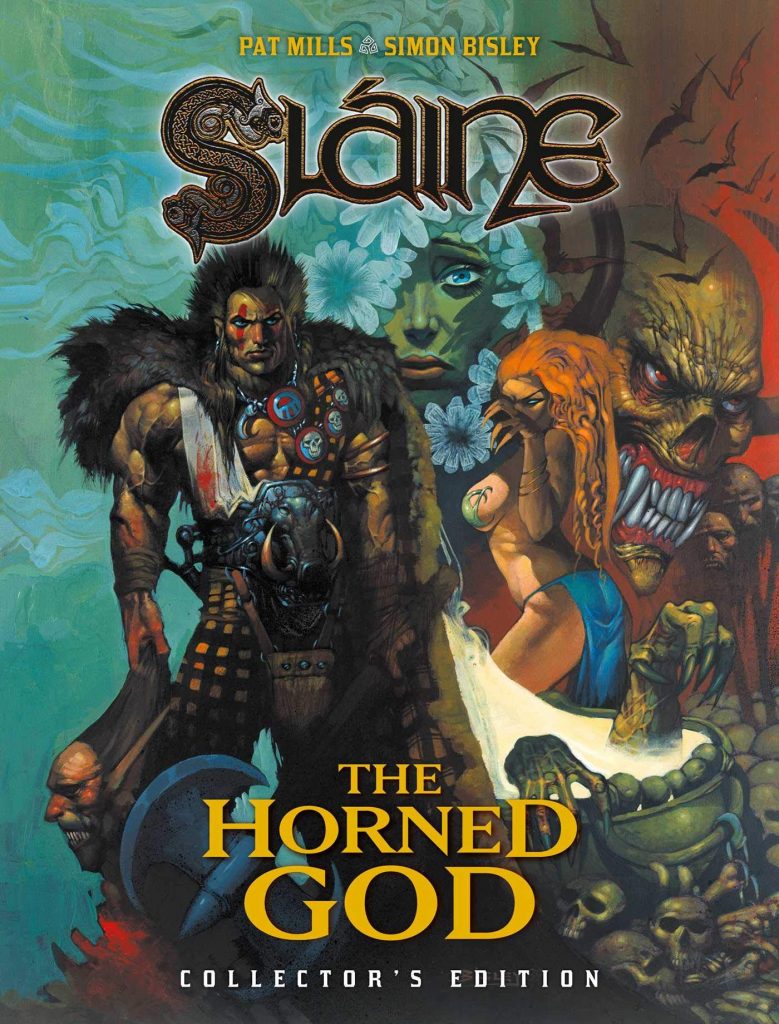

According to Sláine creator Pat Mills, sales for 2000AD rose markedly during the periods that The Horned God was serialised, especially in Europe, which is very unusual for a British comic. Yet it isn’t surprising as the European comic scene has influenced many British creators including Mills and The Horned God’s artist Simon Bisley. Bisley won Best Artist at the 1990 Eagle Awards for this work and the sheer number of editions testify to its being 2000AD‘s best selling graphic novel.

A major contributor to the saga’s success is that it is in colour, the first time for a Sláine story, since at the time only one 2000AD story per issue was coloured and it was usually Judge Dredd. In a way it’s a pity since some earlier artists produced fantastic work that would have looked even better with a touch of paint. No disrespect intended to Bisley, whose artwork is fabulous, astounding nearly thirty years later and marking the point where Sláine truly looked like the Celtic saga Mills had envisioned all along.

The beauty of Horned God is that you don’t have to be familiar with earlier Sláine stories as the most important previous events are cleverly recapped. Sláine MacRoth is now King of the Sessair, but will not be content until he has become High King and united all the tribes. To defeat the Drune Lord Slough Feg and his Fomorian allies, Sláine needs the treasures sacred to the tribes: the Cauldron of Blood, the Silver Sword of the Moon, the Flaming Spear of the Sun and the Holy Stone of Destiny. However this involves the resurrection of Carnun the Horned God, the deity their enemies revere and to fulfil the wishes of Danu the Earth Goddess Sláine may have to sacrifice everything.

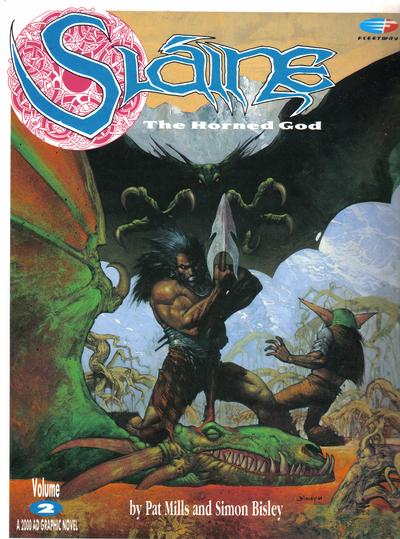

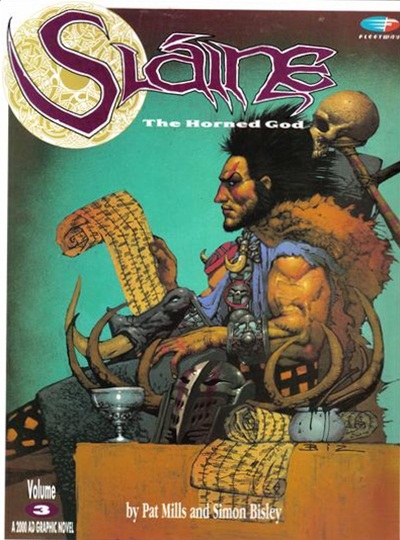

Mills crafts an enthralling story with a fascinating insight into both cultural and religious Celtic beliefs. They can be hard to understand, Celtic mythology not as straightforward as your standard western legends, the pro and con being that The Horned God feels genuinely Celtic and runs like true fantasy. Mills takes the time to explain crucial aspects without over-explaining with his research meticulous, arguably bringing a new understanding to Celtic history and myth. It’s lengthy, originally spanning three separate volumes (Book I-III) which can still be found by intrepid searchers.

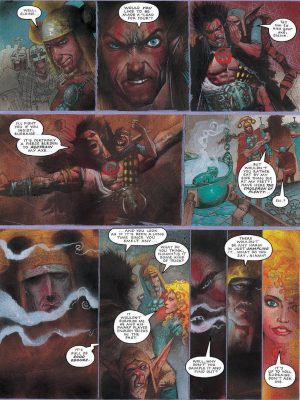

Mills asserts that Horned God would not have worked without Bisley. Gloriously demonstrative in his style he captures both a scowl of distaste and a humorous smirk, a nonchalant pose and a sultry suggestion, roars of triumph and the howls of anguish. The imagery he employs for concepts like the workings of the subconscious are incredible and his depictions of the cast make them personable. Danu is beautiful, fierce and haggard in every expression of her divinity while Sláine’s love Niamh is proud and fierce yet startlingly feminine. You can argue that the art is exploitive, though the way they are written enforces the influential and often equal role women played in Celtic society despite attempts to dilute their importance.

The Horned God is deathly serious, but also wildly humorous, at some points laugh out loud funny, and if Mills’ classic fantasy narration has dated a little, the dialogue is still fresh. Bisley’s art is breathtaking and vivid, worthy of a place among the works of the likes of Frazetta. If you have to read one Sláine book then this is it. If you want more you can always move on to Demon Killer.