Review by Ian Keogh

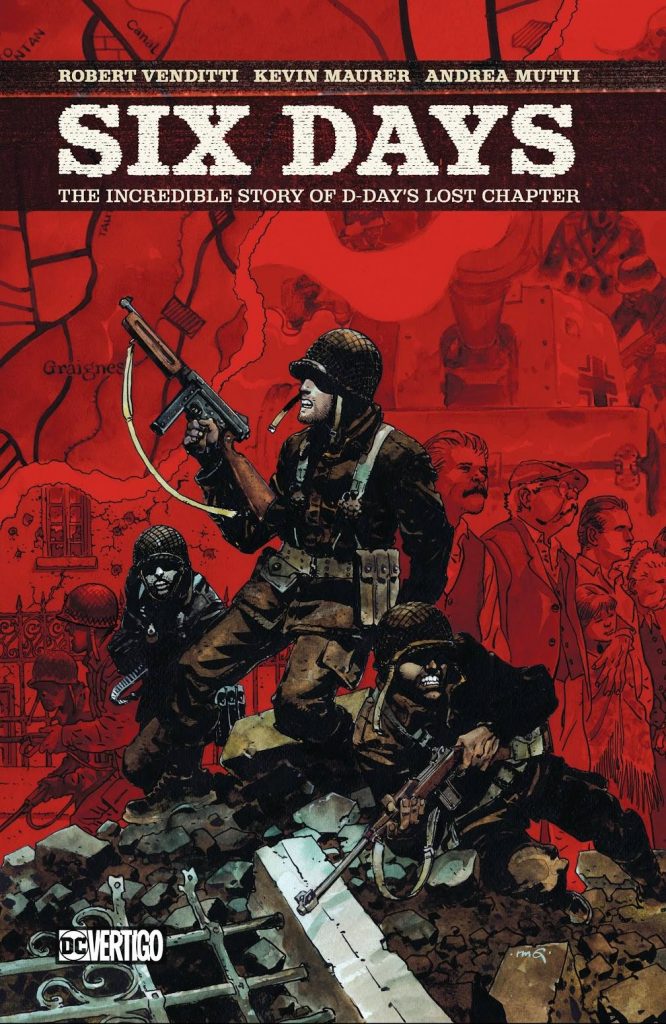

It’s now several generations since every kid knew the significance of D-Day, the codename for the June 6th 1944 pushback into Nazi occupied France that began the liberation of Europe in World War II. Among the allied forces were thousands of American paratroopers dropped into Normandy, one of them Robert Venditti’s uncle.

He was among those dropped in the wrong place, in a marsh near the small town of Graignes a considerable distance from other allied troops, and with a single road the only way into or out of town in either direction. Eventually just under two hundred Americans arrived swelling the population by around a third. Writers Venditti and Kevin Maurer set the scene efficiently, giving us time to know the location, villagers and soldiers as they’re occupied by preparations in the calm before the storm. It brings home the fears of the local people that the war has largely bypassed before the Americans arrived, and a prolonged settling-in occupies half the book, although includes a few brief bursts of action.

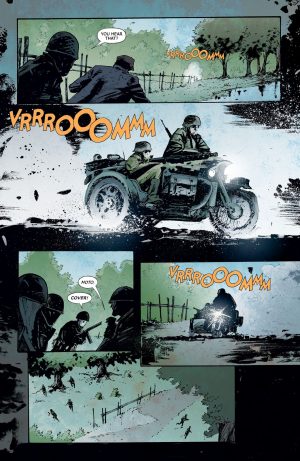

Everything transmits well due to Andrea Mutti’s thoughtful art, never straying from the realms of realism. He’s not the strongest when it comes to conveying facial expressions, but is great with posture and gestures and knows how to set a mood via a well chosen silhouette or a glance through a doorway. The Americans are personified by concentrating on just a few soldiers, and Mutti ensures we come to know them well. When the battle scenes arrive, Mutti invests them with chaos and his looseness is very effective when it comes to moving vehicles. Lee Loughridge uses a limited set of muted colours to bring everything to life, with the bright orange of exploding mortars and the fires they cause standing out.

The battle of Graignes over three days is still commemorated now because a large German force heading North and expecting no opposition was delayed and suffered heavy casualties. A strange omission is not noting the greater significance of the delay. Casualties among the Germans and their late arrival were being responsible for their losing a subsequent battle at Carentan that in part opened a path into France.

Venditti, Maurer and Mutti involve readers with events and ensure an appropriate poignancy, although the subtitle of The Incredible Story of D-Day’s Lost Chapter is overly dramatic in direct contrast to the matter of fact content. World War II produced so many moments of exceptional heroism that it’s inevitable that many don’t receive the recognition they would if occurring under other circumstances. Six Days rectifies this instance, and the understated approach is a fitting testament to Venditti’s uncle and his colleagues.