Review by Ian Keogh

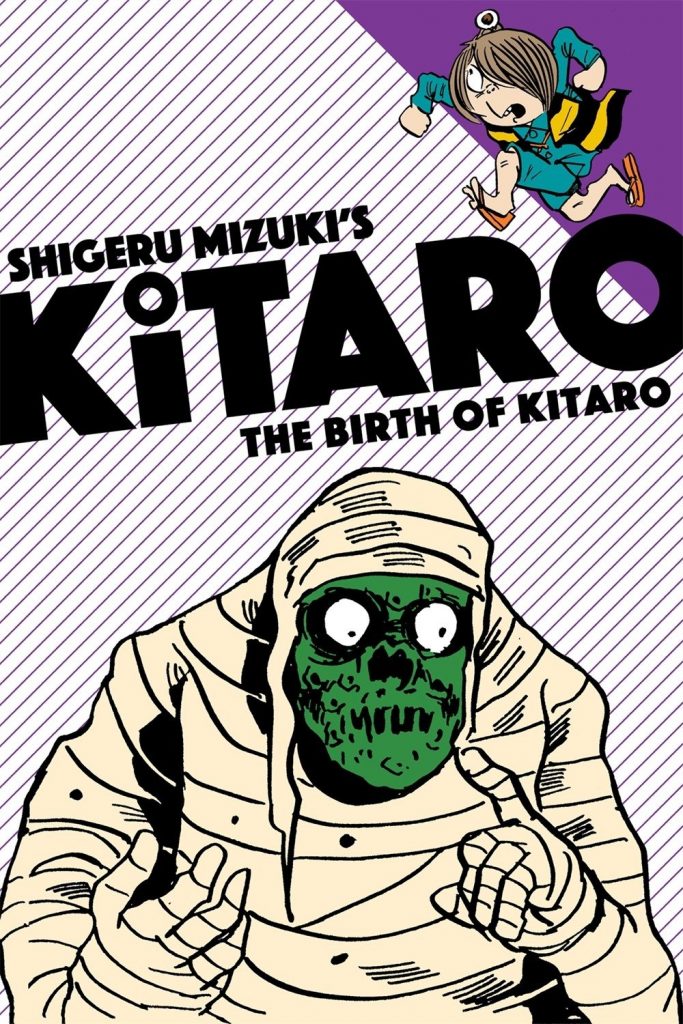

As with many long-running Japanese comics aimed at children, it makes no difference which translated volume is read first, but The Birth of Kitaro is a title inviting the curious reader, suggesting an opening volume. In a couple of ways it is, beginning with the mid-1960s reboot with which creator Shigeru Mizuki refined his Kitaro character. The one-eyed monster child had long been a horror among a long tradition of ghost and monster stories (Yokai), but with this opening story Mizuki redfines him as a sympathetic helper of humanity. This collection opens with the first part of translator Zack Davisson’s contextualisation of the one-eyed monster child within Japanese historical culture, and these informative essays continue over each subssequent Drawn & Quarterly’s volume.

The title story is Mizuki’s absorbtion of Yokai legends to create a continuity, revealing how the Yokai were once Earth’s dominant race, yet retreated as humanity spread, eventually living underground. Kitaro emerges as an infant who literally crawls free of the grave to wander the world, accompanied by his father’s spirit embedded in a walking eyeball. He straddles a strange middleground, older than his six years would suggest, with a protective sympathy for humans often lacking in his fellow Yokai, to whom they’re prey.

Nezumi Otoko will be Kitaro’s untrustworthy companion, and he’s introduced in the second story. Half-Yokai himself, he’s an unscrupulous conman willing to exploit the fears others have of Yokai for financial gain. Mizuki applies a moral code, though, and it’s a rare strip where Otoko doesn’t suffer for his misdeeds.

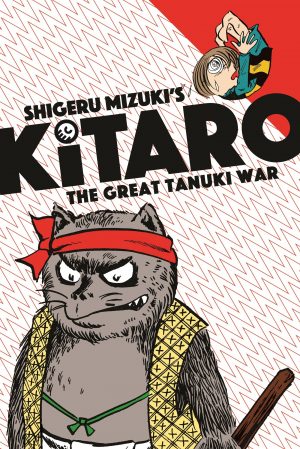

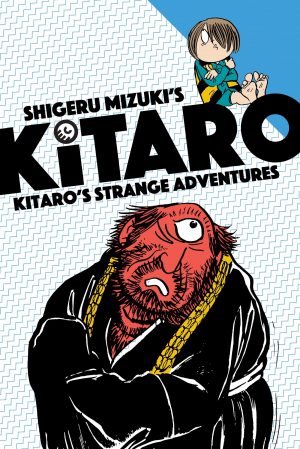

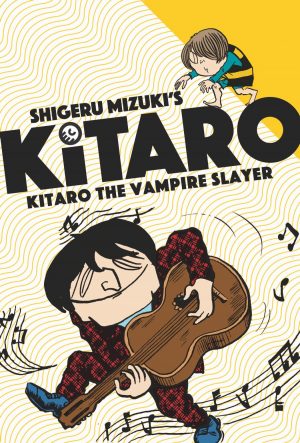

As seen in the sample art, Mizuki mixes simple cartoon people with complex, shaded backgrounds and inventively refined monsters. These are usually based on legends, and Mizuki was an avid collector of old Yokai stories and illustrations, so may have used these to design the creatures Kitaro faces. Despite the inclusion of Yokai, Mizuki aimed his strips at children, who when he began the series were as likely to have been raised on such stories as he had. However, the best children’s material transcends the genre limitations to become a treat for any age, and Mizuki achieves this almost from the start. Such is the ubiquity of Yokai legends with one for almost every occasion or location, there’s never a shortage for Mizuki to draw from, and there’s considerable variety over this opening selection, with Yokai whose realms are the sea, the world of dreams and one that controls the weather.

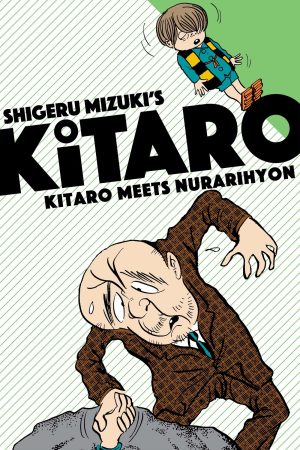

These are funny stories to be enjoyed by all, and there’s more fun to be had in the back pages where Davisson explains more about the Yokai seen in the stories and provides puzzle pages as well. As noted, the books can be enjoyed in any order, but the second part of Davisson’s essay is found in Kitaro Meets Nurarihyon.