Review by Roy Boyd

Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of the Four (which appears just as frequently as The Sign of Four) is perhaps the best of the four full-length Sherlock Holmes novels, partly because it doesn’t include the detours into other stories that mar the remainder. These sometimes felt like the stories that Conan Doyle would rather have been writing, and could easily leave readers feeling short-changed at the lack of Holmes, or even Watson, in the tales.

Our story opens with the world’s only consulting detective partaking of his famous seven-per-cent solution. This was back in the good old days when respectable ladies and gentlemen could visit their pharmacist for a little heroin or cocaine for treating a variety of maladies, or just as a pick-me-up. Then it’s a quick refresher in Holmes’s methods. This is the usual stunning display of abductive reasoning that usually doesn’t stand up too well to a thorough examination, but which is nevertheless always impressive, just like when a magician explains how his trick is achieved (a comparison that Holmes himself uses).

As is so often the case, a puzzling mystery is brought directly to 221B Baker Street, this time by an attractive young lady – Miss Mary Marston – who would go on to have a lasting impact on the domestic and working relationship that existed between Holmes and Watson. There’s a great deal of complicated plot involving stolen treasure, a one-legged man and his strange companion, a mysterious map, betrayals and all sorts of shenanigans meaning the pace doesn’t let up for a minute. Conan Doyle also references the work of some of his contemporaries. The influence of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue can be felt all over the story (including a clever bit of misdirection by Conan Doyle) and he pays homage to another Scot, Robert Louis Stevenson, and his Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde. At the resolution of the adventure, it’s back to the coke for Sherlock, neatly bookending the tale.

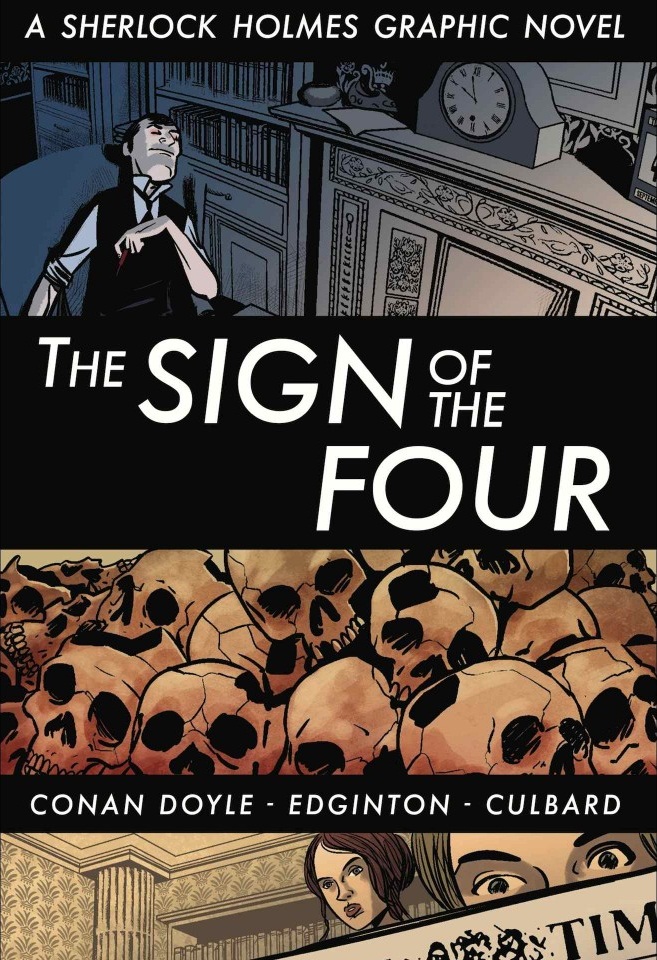

As with the other three books in this series, Ian Edginton credits Conan Doyle as writer, with Edginton merely taking responsibility for panel breakdowns. This is probably very generous, as there’s a great deal of skill involved in knowing what to cut and what to leave in, especially as this adaptation has to work first and foremost as a graphic novel. Artist I.N.J. Culbard’s simplified style helps to keep things moving, and comprehensible, while maintaining enough of a Victorian atmosphere that the stories don’t feel incongruously modernised. It also doesn’t hurt that detective and pulp fiction has rarely been more popular. This is one of the tales that helped to establish the templates that many creators continue to work with, and this adaptation is another worthy addition to the canon.