Review by Ian Keogh

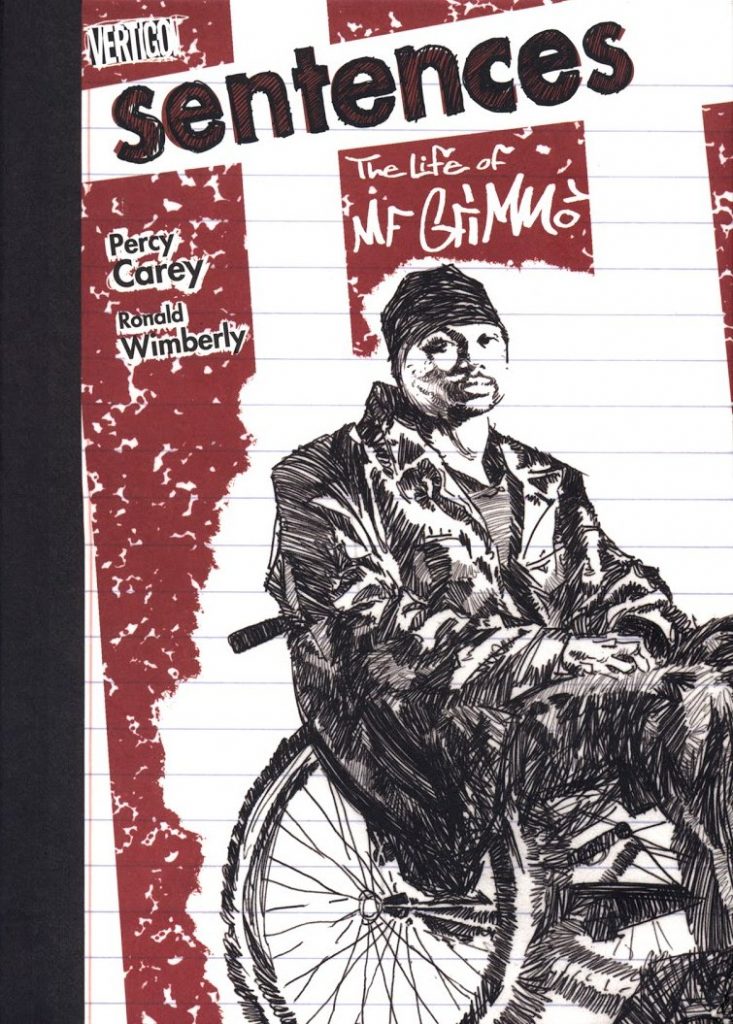

Sentences is a smart guy considering a lifetime defined by fundamentally poor choices. When published in 2007 Percy Carey, alias M.F. Grimm, was 37 and had packed far more into his half lifespan than many would in a full life.

Because Sesame Street was filmed near his New York home the confident Carey scored a regular role as one of the featured children when five. He recalls his mixed neighbourhood as a place of safety as he grew up and his mother as a bastion of common sense not to be messed with. It didn’t stop Carey from drifting into gang culture as a teen, his interests divided between that and a natural talent for MCing, although he notes defying the expectations of others by always carrying a book around with him. However, his memoir isn’t an exercise in whitewash or point scoring. M.F. Grimm knows what he was, knows he took the easy choices, knows he ignored sound advice, and knows where that road led.

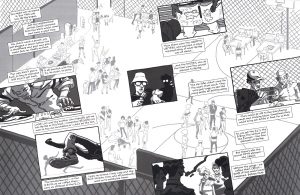

While Carey’s captions set the scene, it’s Ronald Wimberly who supplies the life, drawing us into the yards, school halls and basketball courts of early 1980s New York and beyond. His people ooze personality even when doing something as simple as playing cards on the sample spread, which fully represents Wimberly’s talent, even if he forgot to complete the last few folk at the top. It’s an era and location defining illustration filled with spirit. A counterpart is provided late in the book when Wimberly takes the same approach to analysing life in prison.

In Carey’s case hindsight is a terrible awakener. While still at school he’s shot three times and almost beaten to death, yet the lesson taken was one of invulnerability, not huge luck. Even when he moved to Los Angeles and was earning amounts most people would be happy with writing hit lyrics, Carey didn’t make much of an effort to extricate himself from gang culture. Returning to New York he had the talent (just listen to the Scars and Memories compilation), all the right connections, and was on the verge of having his career take off when those mistakes came home to roost. Since 1994 he’s been confined to a wheelchair. Interestingly, while the details of the incident are fully described, Carey avoids the specifics of what might have caused it. He’s more forthcoming about his later jail sentence. Yes, he was sold out, but he was trying to buy guns in the first place.

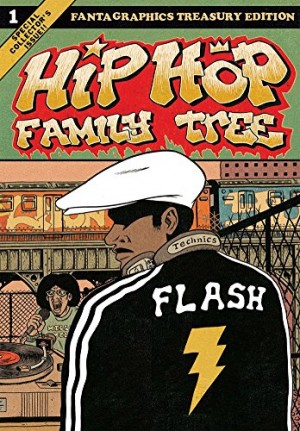

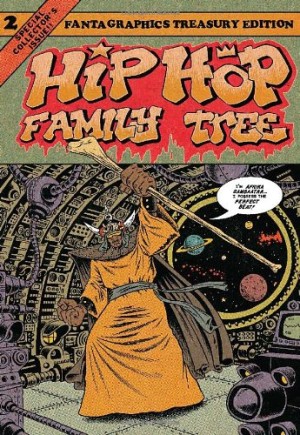

The 2007 publication of Sentences was four years after Carey’s release from jail, and a condition of that was his being on lifetime parole. So, while honest and unsentimental, common sense and the threat of prosecution dictates Sentences is not the full disclosure, something referred to on the final pages. That’s not fatal, but it leaves obvious gaps, presenting effects without a corresponding amount of cause. The contracted storytelling also runs into problems. Lyrically, Grimm’s a clever and observant writer with points to make, but his form of writing thrives on contraction, and there are several places needing expansion. His recording career for one. However, much of the criticism is irrelevant in the face of what is here. All too often hip hop culture glorifies the unpalatable, and there’s none of that, Carey staking his turf as a matter of fact and providing a warning without belabouring the point. Sentences is cautionary but doesn’t talk down, opening the door for a compelling glimpse that’s phenomenally drawn.