Review by Frank Plowright

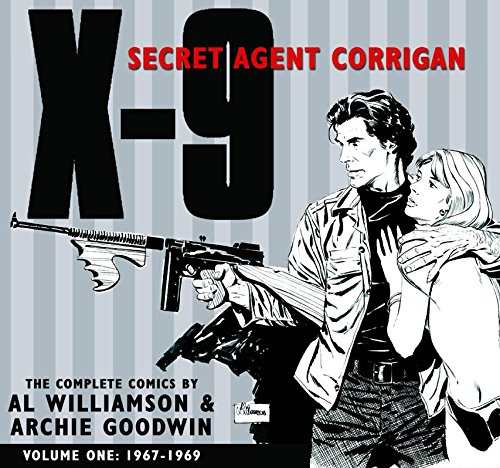

Secret Agent Corrigan, renamed from its earlier incarnation of Secret Agent X-9 entered a golden era in 1967, just shy of 35 years after it began running in American newspapers. Created by mystery writer Dashiel Hammett and Alex Raymond, X-9 wasn’t given a conventional name until almost a decade after his introduction. Neither founding creator stayed beyond three years, yet the strip survived well enough without them, being continued for decades by others barely recalled today.

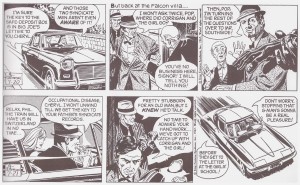

Al Williamson was appointed artist to replace Bob Lubbers, whose tenure began in 1960. Previously most highly regarded for the imaginative science fiction landscapes he created for EC comics in the 1950s, here Williamson ensures the strip is grounded in the realities of the times. He’s resolutely up to date in depicting society as it was was for most 1960s Americans in a major city. In this collection at least, the rapid spread of the counterculture is given but a nod by the presence of an artist with goatee and polo neck shirt. The women are dressed in the classic fashions of Givenchy or the more adventurous Courrèges, while at the outset Corrigan’s hat is never absent for too many strips and his boss is a pipe smoker, the very essence of 1950s right thinking reliability. Those familiar with them will recognise the Triumph Herald or Chevrolet Corvette Stingray (both in the sample strips) as they cruise the streets.

It’s for Williamson’s stylish elegance that Secret Agent Corrigan is remembered, but he was but one element of a partnership and Archie Goodwin’s contribution deserves equal consideration. He got the gig in no small part because he was Williamson’s pal and Williamson lobbied for him, but on every single strip he proves why that was the right decision. Goodwin’s versatility had been proved writing quirky material for Warren’s horror and more serious war titles, but when it came to the disciplines of a daily adventure strip, he was untested, although his first professional sale had been to a mystery magazine. He adapted astonishingly well and very rapidly. His first three tales occupy roughly seven months of original publication, and the varied tone is exemplary. These strips feature a defected Soviet agent, now a target, a covert mining operation in South America, and the secrets of a one-time Mafia boss who fled to France, now willing to cut a deal with the FBI. Each presents a new threat in a different locale, and that’s a pattern followed throughout the almost three years of daily strips presented in this collection. Not that it’s of consequence, but for those paying attention back in the 1960s Goodwin also established minor elements of continuity.

Williamson’s name appears on every strip, but he doesn’t draw them all. There’s an early week of fill-ins by Neal Adams, mimicking the style extremely closely, and Stanley Pitt produces three months of continuity to close the book. His inking possesses a greater flourish about it, reminiscent of Russ Manning, although his credited stint begins with the work of a different, clumsier and anonymous artist.

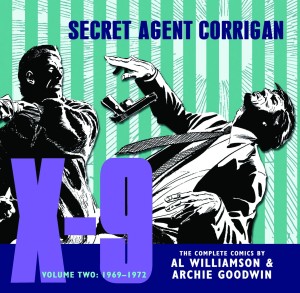

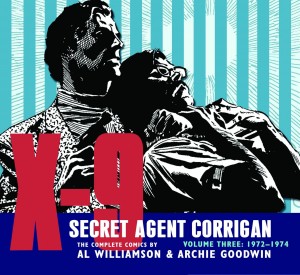

The disciplines of a daily adventure strip are a unique artistic form, and can rapidly lead to repetition and dead ends. That’s not apparent in the work of Goodwin and Williamson. Now created fifty years ago, Secret Agent Corrigan has lost none of its charm, and improves in subsequent volumes.