Review by Frank Plowright

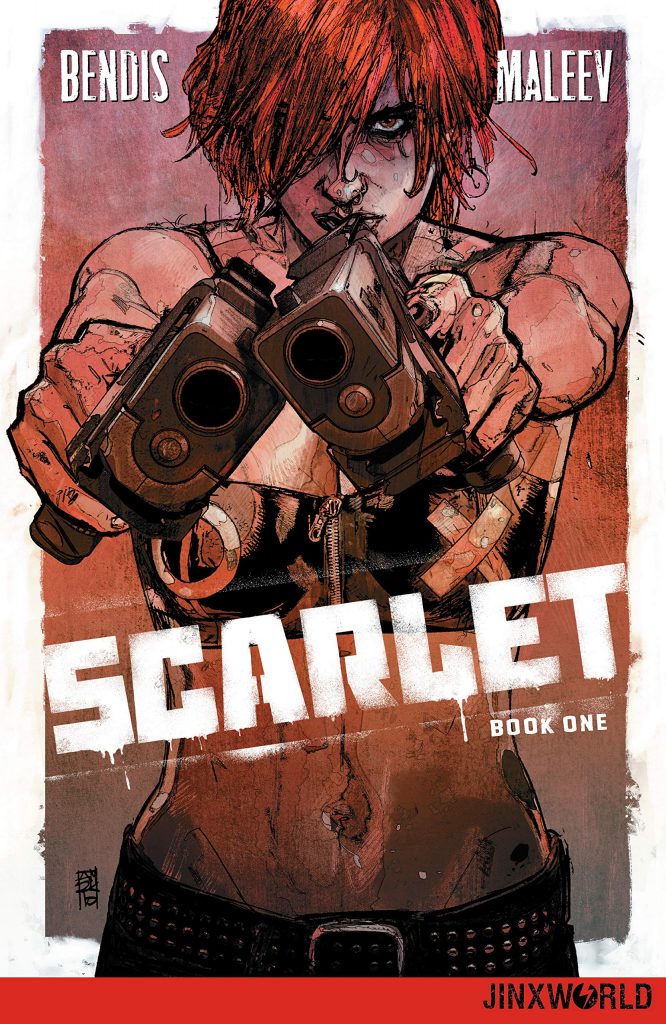

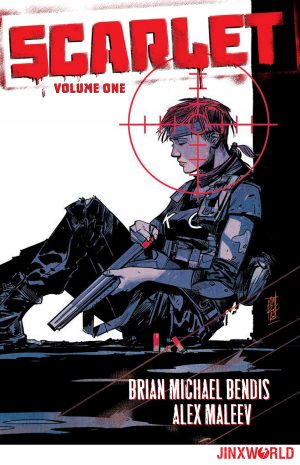

A great opening scene instantly pulls readers into Scarlet. We see the title character and her distinctive bright red hair murdering a policeman and going through his wallet. It’s accompanied by Scarlet addressing readers directly pointing out that no matter what it looks like, it’s a scene that needs contextualising, and the remainder of the story provides that context.

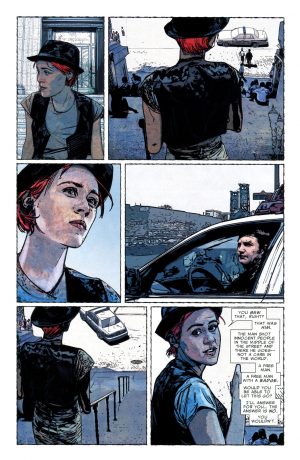

Much of Scarlet may seem political, but it isn’t really, it’s about perspective. An early scene has Scarlet and her friends hanging about enjoying themselves, but conforming to the ignorant older person’s judgemental profile of drug users. In fact the drug user is the policeman giving them grief, addicted to over the counter cough medicine, and who takes the opportunity to grope Scarlet during his spurious search. That sets off a series of tragic events, and the question Bendis keeps asking by implication is how much should people put up with to keep the world running as it is? What amount of collateral damage is acceptable to produce the illusion of safety and protection? These questions have become ever more pertinent in the years since publication. Scarlet continues to address the audience, to challenge preconceptions, and that feeds into her primary mission of cleaning up Portland.

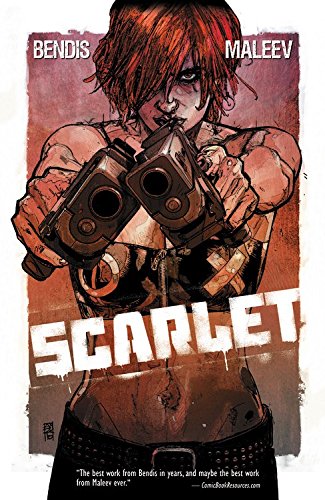

Bendis and artist Alex Maleev are a proven creative combination after an acclaimed run on Daredevil (start with Underboss), and their collaborating on another gritty crime series is cause for celebration. Maleev’s digitally processed art isn’t to all tastes, and he’s not great with movement, but each of his grainy panels isn’t far removed from a snapshot on a dull day, Scarlet’s red hair picking her out as the item intended to draw the eye. This works especially well on detailed city scenes featuring big crowds.

Scarlet sees Bendis stretching himself as a writer, trying different techniques, some of which work better than others. Scarlet addressing the audience directly explains her more fully than any amount of narrative captions would. It can be regarded as presenting a character the way she is, or as indicating that the audience is her only confessional release, because in places Bendis has her run off at the mouth a little too much. She does preach (to the converted) at times. Also novel, but entirely unrequired, are several pages flashing through the lives of individuals. They add nothing, and pause an already slow-moving story.

Scarlet’s isn’t the only perspective. What she does requires an official response, and we see out of touch officials not comprehending how their world is changing, and their methods of dealing with things in a flashmob era are nearly redundant. The only police officer able to provide the voice of reason also addresses readers, and she has a larger role in Book 2. Alternatively both volumes are combined for Scarlet: Absolute Edition.

What rolls out in Scarlet is a notably predictive tap into the zeitgeist, with increasing disenchantment about political systems and disenfranchised people personalised in Scarlet herself. It’s empowering and insightful, and very much intriguing.