Review by Ian Keogh

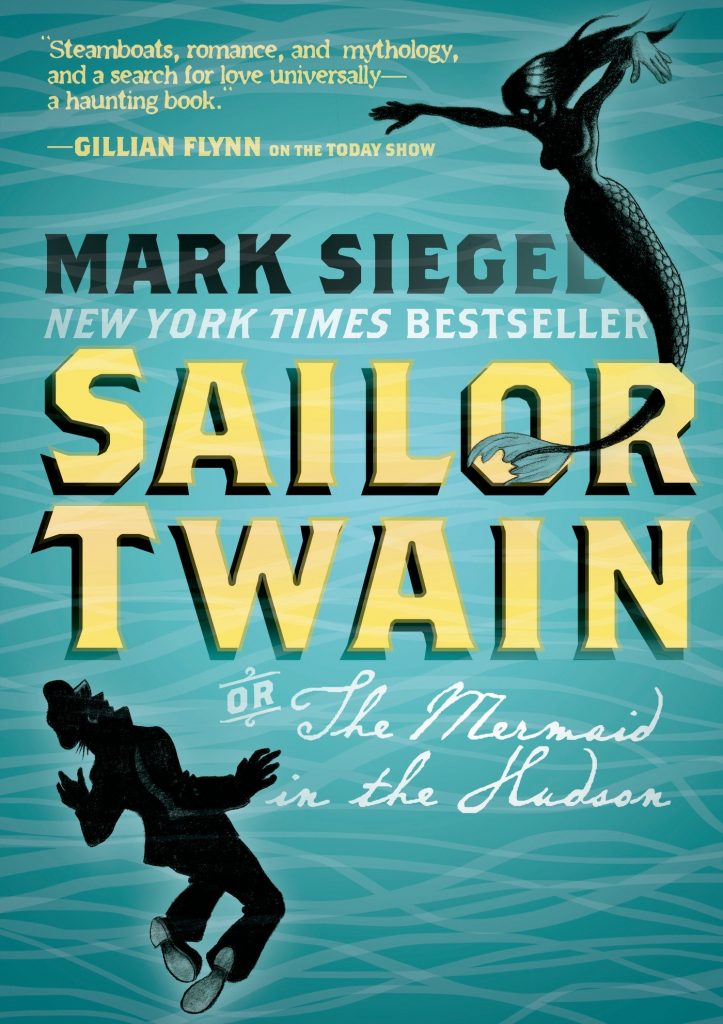

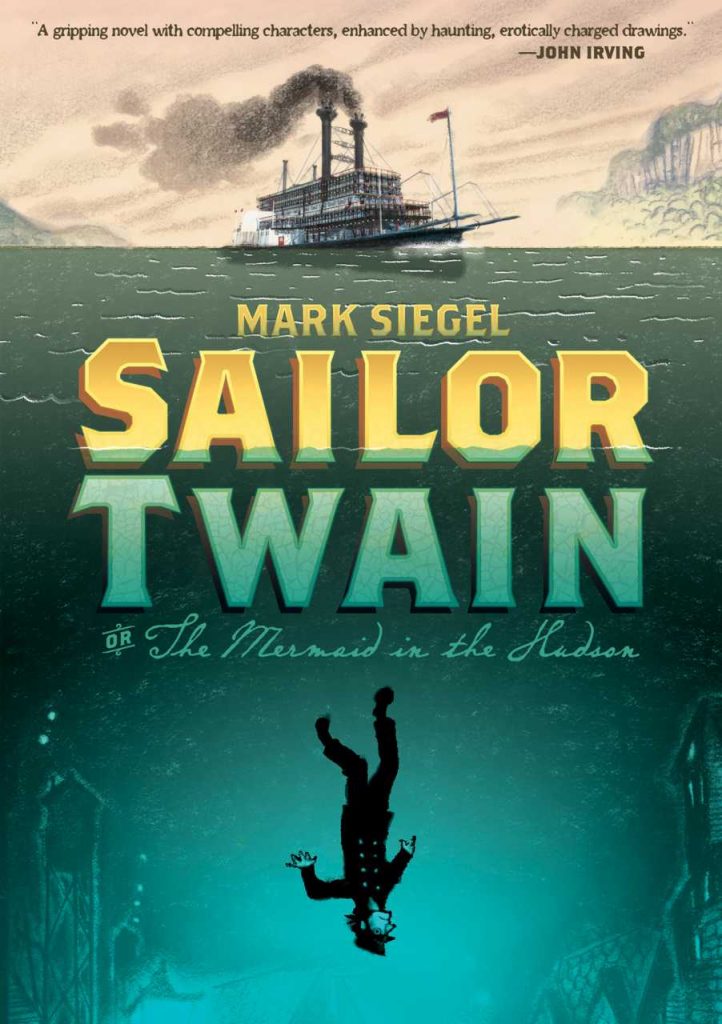

Sailor Twain is an incredibly warm and tragic story, and Mark Siegel’s telling of it is great, right from an overture of a woman seeking out Sailor Twain himself in a seedy waterfront bar. It invites the reader in, sits them down, and piques their curiosity before the tale proper begins. And what a tale it is, an epic, rich storytelling experience deliberately constructed to echo the density of the late 19th century novel.

In 1887 Twain captains a riverboat for the Lafayette line, run by the libertine younger brother of the firm’s French founder, now missing and believed dead by all but his brother. The boats take passengers up and down the Hudson river, and the lead character’s name and the riverboat setting practically invite comparisons to Huckleberry Finn, underlined by copies of that book being seen. Sailor Twain has a similar discursive nature. We learn very gradually of Twain, first the person he is, then the situation of his life, about which there’s a mystery. He’s a deliberate contrast to the open Lafayette, who constantly explains his conquests, much to the loyal Twain’s embarrassment. The reason for the subtitle is that mermaids become more and more important to the plot. Lafayette corresponds with a reclusive writer who’s the nearest America has to an authority on mermaids, while Twain actually rescues one.

Siegel’s illustration is deceptive. The charcoal figures are kept relatively simple, occasionally smudged a little around the edges to give them a softness, a trick also used by Peter Kuper, but when Siegel’s attention turns to the steamboat, its engine room or a map, the detail is immense. The use of the boat and the conditions it meets as visual metaphors for the prevailing emotional turmoil is subtle and effective. So is switching the scenery for a pivotal scene toward the end.

The way Sailor Twain twists around is wonderful, never precisely pinned to a particular purpose. Just when it appears to be pegging itself to the fantasy mast, Siegel swerves and instead dives into biblical interpretation and the social expectations of the times. There’s a fantasy sequence, and a tragic love story, and the extrapolation of what mermaids were in old stories, not the cute and sympathetic Disney version, but selfish creatures with their own agenda, one deadly to humans. The central issue eventually becomes how Twain will survive. We know he has, and we know the woman who he met in the bar during the prologue, but is his soul intact?

As much fun as it is spending time with a fabulist, this avoids perfection by not enriching Twain’s personal life to any great degree. We know he has a wife, know she’s ailing, and see him all-but ignoring her, but not enough time is spent with her to give the finale the gravitas it needs. Never mind. The journey is the thing, and it’s great.